OK, so things don’t really vanish anymore: even the most limited film release will (most likely, eventually) find its way onto some streaming service or into some DVD bargain bin assuming that those still exist by the time this sentence finishes. In other words, while the title of In Review Online’s new monthly feature devoted to current domestic and international arthouse releases in theaters will hopefully bring attention to a deeply underrated (even by us) Kiyoshi Kurosawa film, it isn’t a perfect title. Nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to catch-up with films before some… other things happen. | Oscar season is over, thank God, and we have embarked on the season of small and specialty distributors rolling out some of the fall festival circuit’s less commercial, more overtly arthouse offerings. This month brings no shortage of films that fit that bill, including: a pair of 2019 Cannes competition films, the Dardennes’ Young Ahmed and Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers; Pedro Costa’s latest, Vitalina Varela; fall circuit mainstays Balloon, I Was at Home, But.., and A White, White Day, among other successes and misfires.

Vitalina Varela

Winner of last year’s Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival, Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela immediately asserts itself as an artistic and conceptual distillation, if not culmination, of a career that has folded portraiture, theater, anti-colonial politics, and class solidarity into a cinema that understands itself as a work that persists under, if not against, ‘the cinema’. While refining Costa’s artistic and conceptual sensibilities, this latest film may be most notable, at least to those familiar with the director, for its changing of the temporal rules that have up until now defined the occupants of Fontainhas. Since 2000’s In Vanda’s Room, many names and faces have recurred in Costa’s cinema as it has taken the aforementioned community as its object, with the spatial and temporal progression between that film and 2014’s Horse Money being decidedly linear; all of it a witness to an abiding sameness of material and mental degradation in the throes of poverty and the violence of history. Yet in the starkest of contrasts, Vitalina Varela asserts itself as an interruption of such linearity. While still following the director’s well-known docu-fictive strategies, the film—which suspends the temporal progression of his filmography at large and acts as a spiritual prequel or parallel temporality to the director’s 2014 work, presents events described by Vitalina in that film, chiefly her arrival in Portugal from Cape Verde not long after the burial of her runaway husband, as she comes to terms with the facts of his abandonment and the destitution of his existence in Portugal—is the most forceful expression of Costa’s desire, or fight even, in his own words, to “respect time… to be with time, on the side of time” as he and his actors excavate the memories that haunt their waking and dreaming. Horse Money and Vitalina Varela are united as films dedicated to the traumas, secrets, and selective recollections of the people and characters of Ventura and Vitalina—who take precedence in each, respectively—and the attempt to give them back history and the time taken from them. Each film contends with figures and images of the past invading the present of their protagonists, and if Horse Money conceivably ends in failure—a repossession by historical violence—Vitalina Varela, which sees visions or dreams of a young Vitalina in her then under-construction home on the hills of Cape Verde reverberate out of the past into the mind of the older Vitalina in Portugal, is its opposite. “It’s all about the work”, remarks Costa, and fittingly, for the words are not just emblematic of the production itself and the director’s wider philosophy—which is actively challenging cinema and its means of operation and the ends they are directed toward—but of the very themes of the film: the attempt to not only to stand with time but to return agency and free a person to build again. Vitalina Varela will rightly be celebrated for the beauty of its claustrophobic Vermeer-esque, Lewton-inspired compositions; methodical editing; and languorous shooting rhythms, but it is the denouement that confirms the film as a work of extraordinary conceptual and humanistic vision: a movement of character out of frame and a cut that connects a rejection of present isolation with the joy of a Cape Verdean past. In these closing moments, the viewer witnesses a restoration of agency through an uncompromising respect for time; not only might the character have found the capacity to build again, but all the more so might the very person of Vitalina herself have—through a seizing of the tools of cinema and its collapsing of the rules of time—returned her life to herself. Matt McCracken

Young Ahmed

Jean Pierre & Luc Dardenne have created a corpus of films strong enough to build the case that they are among the most important European directors working of the past two decades; their formal rigor and the way in which their approach has influenced so many filmmakers with similar cinematographic sensibilities is undeniable. One of the Dardennes most interesting characteristics, though, is their propensity for compassion for every character that they put on the screen, from a child murderer, to a kidnapper, to a man won’t budge in a work negotiation. All people are capable of either redeeming themselves or being forgiven. All of that was true, at least, until now. The Dardennes’ latest film — which premiered at this year’s Cannes festival, was met with a mixed reception and loads of controversy — features a young Muslim man, Ahmed (Idir Ben Addi), who tries to murder his apostate teacher for using songs and other methods, as opposed to strictly the Quran. In many ways, Young Ahmed follows a moral principle similar to that of Shunji Iwai’s much more successful, and gut-wrenching, All About Lily Chou Chou: it’s about the way in which children are easily manipulated when confronted with bad influences, and especially when those circumstances are compounded by mental instability. While this ambition is commendable, and their efforts can be pointed — especially when it comes to the way they perceive institutions and programs meant to help children, like Ahmed, who feel alienated by society — their Christian point of view (widely recognized and commented on throughout their careers) impedes sincere attachment to Ahmed, disallowing that glimpse of redemption. Ahmed’s blind devotion to his religion is rendered strange and inherently problematic, especially when it comes down to what society believes the boundaries between religion and public life should be. There is an intention here to push forward and attack these questions, but the way the Dardennes do it is brash and at times difficult to watch; their lack of empathy for Ahmed, evidenced by the amount of punishment he has to go through, seems a bit too much, especially in context with the directors’ previous films. Jaime Grijalba Gomez

The Whistlers

Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers is a tight, satisfying crime yarn — even if its small quirks and arthouse sheen sometimes get in the way of the good time its offering. Setting out not to reinvent the wheel so much as spin it, and spin it well, the Romanian director’s latest checks all the boxes one would expect of its genre: murder, triple crosses, misbegotten romance. Cristi (Vlad Ivanov), a crooked cop, seeks to set free his incarcerated, drug-smuggling boss, with the help of some affiliates. But to do so successfully, he and the others must travel to La Gomera, in the Canary Islands, to learn Silbo Gomero, a language that transcribes Spanish (and, now, Romanian) into whistling. The gist is that Cristi will communicate, via whistle, when freeing his boss from a Bucharest prison. It’s a strange contrivance of a device that Porumboiu only manages to make great use of in the film’s just-as-contrived, too sentimental epilogue. But it gets things out of Bucharest for a time, contrasting the drab Romanian city with the more vibrant landscapes of the Canaries, lending the film an air of globe-trotting adventure. Though the whistling is the only real wrinkle in the otherwise standard police procedural narrative, Porumboiu glosses up the proceedings with an ever steady camera, some psychologically expressive lighting, and the sorts of narrative digressions that are usually reserved for films twice as long. Those digressions, too, are efficient, delivering plot and characterization simultaneously without much fanfare. A scene between Cristi and his priest, for instance, reveals both the officer’s uneasy home life and how his superiors in the department catch on to his double agent status. These moments add intrigue, instead of bloat, and by the time bullets finally fly, The Whistlers has worked itself into a series of thrilling knots — though ones that do come untied a bit too easily. Christopher Mello

I Was at Home, but…

At right around the halfway mark of writer-director Angela Schanelec’s latest film, I Was at Home, But…, recently widowed mother Astrid (Maren Eggert) goes off on a literal five-minute rant about how actors and actresses are nothing more than liars, and that the deception — especially in comparison to the reality that exists around her — makes her sick. This is a striking moment for a number of reasons. Until this point, Schanelec has communicated primarily through image alone, presenting a series of carefully composed static shots whose overall meaning, even when taken cumulatively, seems opaque at best: a donkey and a dog sharing a room in an abandoned countryside home; the purchase of a bicycle; a young boy returning home after a seemingly unexplained absence; a choreographed dance in a hospital room. While the mere presence of sustained dialogue is startling in and of itself, what proves especially surprising is the bluntness of the messaging. Why is Schanelec so artlessly dropping what basically amounts to her work’s thesis right into the middle of the film? This is, after all, an actress in a film discussing acting as subterfuge. This gambit forces the viewer to reorient, and in reflecting on everything that came before this interlude, it becomes clear that Schanelec is commenting on both the contradictory nature of life itself and the duality of man, with the film as a whole serving as the ultimate example. The contradictions are endless, from a strong-willed and independent woman constantly seeking validation from every male she meets, to a couple experiencing relationship problems as one of its participants craves independence even while acknowledging feelings of love. Even its formalism, especially Schanelec’s reliance on extended long takes, serves to create a sense of realism while simultaneously highlighting the artifice of the proceedings. The problem is that once the viewer figures out what Schanelec is attempting to do, her work takes on the air not of art, but of academic exercise. This would be less of a problem if the filmmaking itself were stronger — while there is certainly artfulness on display, from a technical standpoint, there is nothing here that hasn’t been done before. Schanelec continues to hammers home her point all the way to film’s end, with an extended bit involving a dispassionate middle school production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and emphasizing what she could indeed learn from the Bard — enlightenment and entertainment are not mutually exclusive. I Was at Home, But… is instead admirable but obnoxious. If we want to consider that a contradiction, then I guess Schanelec has succeeded. Steven Warner

Balloon

Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s artistic intention, in both his films and short stories, has been to realistically depict the daily lives of Tibetans, without the exoticizing lens employed by others who’ve made films about them — especially those made by non-Tibetans. Balloon continues this mission, with a potent yet subtle streak of surrealism and mysticism. The film is set in the early 1980s, shortly after China imposed its one-child policy (which was slightly relaxed for ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans), including stiff fines for violators of the policy. This is the historical backdrop through which we view the lives of a rural Tibetan family of farmers. Dargye (Jinpa) and his wife Drolkar (Sonam Wangmo) live with Dargye’s father and their two rambunctious young sons, whose playful acts of mischief play a large role in driving this narrative. Initial scenes often play as a subtly droll sex comedy, as the kids play with “balloons” (which turn out to be actually blown-up condoms given to their parents by the local clinic for family planning). Dargye has a very pronounced sex drive — he’s jokingly compared to the rams he herds for a living — which causes potential financial danger for the family, as he must be careful not to get his wife pregnant again, lest he incur a fine. His boys, who continually find hidden condoms, cause all sorts of trouble for the family, who live in a very conservative and easily scandalized rural Tibetan community. (Much humor is mined from the fact that the farm animals have far more sexual freedom than the humans who raise them.) A more serious subplot concerning Drolkar’s sister (Yangshik Tso), now a Buddhist nun, serves as counterpoint. She runs into her old lover (Kunde), whose perceived mistreatment drove her to the monastery, and he gives her a novel that he wrote, which was inspired by their relationship, hoping to clear up, in his words, a “misunderstanding” about what happened between them. Tseden relates this beautifully told tale through intimate, expressive camerawork, vivid depictions of the dreams and visions of its characters, and vibrant performances by actors who exhibit the authenticity of non-professionals — even though they mostly aren’t. The Tibetan Buddhist belief in reincarnation figures largely in this story, and Tseden cleverly connects this with China’s state-imposed family planning to deliver an unstated, but unmistakable, indictment of the ways religious beliefs and authoritarian governments collude to deny women control of their own bodies and destinies. Christopher Bourne

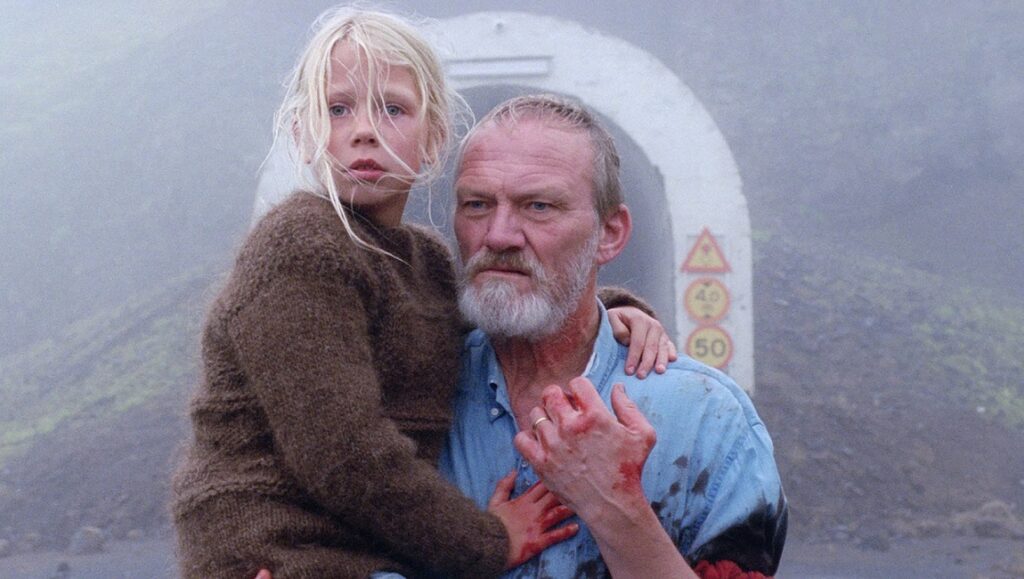

A White, White Day

Iceland’s Oscar entry this year, A White, White Day is a somber bereavement drama in which police chief Ingimundur (Ingvar Sigurdsson), who is grieving the loss of his wife in a car accident, stumbles upon vague evidence among her possessions that she has been having an affair with a local neighbour. Despite the suggestion that her supposed indiscretion could provide a “case” for this inspector to solve, the film shirks any sort of mystery angle, instead psychologically probing the man’s mental state, as well as his relationship with his daughter and granddaughter. For a character study, A White, White Day is as frustratingly closed off as its subject, as after all that follows, it never feels as if Ingimundur has been excavated. Director Hlynur Pálmason has a habit of cutting from scenes just as exchanges start to build, or shifting conversation topics away from matters of substance – three scenes in which Ingimundur sees a therapist offer relatively little about his character, while there is an active refusal to unravel any of his issues in a way that could be conceived as convenient. Resultantly, A White, White Day possesses some merit as a measured, convincing adult drama, but its continual opaqueness is often maddening. While films about grief tend to aim for realization and acceptance for its characters, Pálmason’s approach to this template feels way too uneven to generate much pathos, led by two intensely violent exchanges in the last act designed to confront the reality of his wife’s infidelity, but which feel distractingly jarring. A White, White Day eventually makes clear its message about both the difficulty and necessity of moving on from tragedy, and his approach here keeps the proceedings from becoming hackneyed. The issue is that, by this final stretch, Pálmason may well have alienated anybody from caring. Calum Reed

And Then We Danced

A familiar tale rears its head in Levin Akin‘s And Then We Danced, this year’s submission from Sweden for the International Feature Film Oscar. By their nature, teenaged coming-out stories always provide room for empathy, yet it remains a challenge to make such stories feel novel. This film stands out by introducing us to the art of Georgian dance, as fledgling dancer Mareb (Levan Gelbakhiani) falls for Irakli (Bachi Valishvili), the new boy and arch rival in his troupe. As a window into this lesser-known art form, then, And Then We Danced has a certain unique flavor to it, despite its wholly predictable story beats, which stay close to the tried-and-tested depiction of guilt-edged attraction. Thankfully, things gets much less rote in its second half, as Mareb’s sexual awakening reaches full flow and his various relationships become charged with complexity. Young actor Gelbakhiani proves quite the discovery, exhibiting the sheer unadulterated joy of being in his first sexual relationship. Curiously, you are forced to wonder how Mareb’s homosexuality comes as such a revelation for many around him, given that his feminine traits as a dancer are obvious (and highlighted in the film by his instructor) from the outset. Perhaps some of that can be attributed to the lack of visibility of queerness in Georgia; the LGBT culture in Tbilisi, in particular, comes across as particularly endangered. Despite this being Sweden’s entry (the director and producers are of Swedish origin), And Then We Danced details a particularly Georgian experience that hinges on that nation’s overall intolerance towards minorities. The eventual, hard-hitting resolution for Mareb drives that fact home, bluntly reminding those part of more open communities how fortunate they really are. Calum Reed

Saint Frances

For his feature film debut, director Alex Thompson teams up with screenwriter and actress Kelly O’Sullivan, and together they dive into an investigation of the hardships that women face in the contemporary world. Saint Frances tackles issues of gender and homosexuality, as well as racial matters, and even abortion and other resultant concepts surrounding maternity — and the film fuses these themes with the personal narrative crises of its characters. It’s a shame, then, that Thompson’s filmmaking sticks to the safe and familiar territory of a lo-fi indie, never pushing its aesthetic to places that might challenge the viewer like its subject matter does: naturalistic performances, shaky handheld camera, abrupt (and yet at this point standard) editing, and scattered snatches of soundtrack here and there. As a result, the strong messages feel simplified, too easy-to-grasp. (It doesn’t help, either, that Thompson and O’Sullivan too often resort to the foil of ‘evil’ conservative characters.) What helps prevent Saint Frances from being a bigger failure are sporadic, intimate, and natural moments shared between O’Sullivan’s Bridget and young Ramona Edith Williams’s Frances — a duo whose chemistry has the ability to galvanize and bring freewheeling energy to otherwise humdrum plot beats. That dynamic within the film provides an almost satisfying compliment to its narrative ambitions: six-year-old Frances’s influence is like that of a spiritual guide or guardian angel, as she helps her troubled, melancholic nanny Bridget locate a sense of love and self-discovery in her life. When, in the final scene, Frances leaves Bridget and heads to school, she shouts happily, repeating after her nanny: “I’m smart, I’m brave, I’m the coolest”. These are not only the words Bridget utters to little Frances, but also a constant reminder to herself. If only the film itself possessed such singular enthusiasm and confidence. Ayeen Forootan

After Midnight

Labels are always reductive and usually insulting. They also have the potential to be illustrative, as is the case when I say that the new horror flick After Midnight is perhaps the most hipster film I’ve ever seen. An affinity for beards, craft beer, tattoos, and antebellum architecture does not mean a person lacks individuality or creativity, but this film captures the true essence of an Urban Dictionary entry with such precision that it suggests the possibility of a stealth satire. No filmmaker could possess such little self-awareness, right? Jeremy Gardner pulls triple-duty here, co-directing, writing and starring as Hank, a hard-drinking, bearded, tattoo-sporting bar owner living in the backwoods sticks of New Orleans in a big, plantation-style fixer-upper. His girlfriend of 13 years, wine-connoisseur Abby (Brea Grant), left him one month ago for reasons unclear. Since her departure, Hank is visited each night by some sort of monster that comes scratching at this door, howling at the moon. Is this monster real? Or is it a metaphor? Or is it both real and metaphor? Gardner and co-director Joe Stella have actually tried their hand at DIY horror once before, with 2015’s Tex Montana Will Survive — although that effort certainly skewed more comedic — and the filmmaking itself proves sturdy. They show an assured hand, whether it be tracking their protagonist and a friend through the brush of the backwoods, brightly colored shirts highlighted against a sea of beige, to a clever sequence set in the recesses of night where the monster is illuminated only in the flashes of shotgun blasts. The editing is also on-point, as they favor abrupt sounds accompanying scene changes that serve as their own spin on shock cuts — perhaps not original, but at least effective here. But when After Midnight commences a 20-minute unbroken shot near the film’s end, its true purpose is revealed as our troubled lovers finally lay bare their relationship issues. There’s nothing fancy going on compositionally, just two individuals sitting on a porch, drinking, trying to come to terms with love lost. It is emotionally raw, angling for heartbreaking, but also manipulative and infuriating, because you know exactly what Gardner and Stella are doing here: upending genre conventions, and doing it in the most banal and obvious ways possible. There is a smugness to the proceedings that irritates, the clearly talented filmmakers devoting their impressive skills to an endeavor that is the definition of what “indie” filmmaking has become today — detachment posing as earnestness. And this is what makes it impossible to tell if these types of films are satires, because the greatest trick a hipster ever pulled was couching sincerity in irony. I am not the least bit surprised that filmmakers Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead — two guys who basically invented this type of film with 2014’s Spring and 2017’s The Endless — have a producing credit here, or that Benson himself pops up in a supporting role. Just wake my bearded ass up from my craft beer coma whenever these dudes finally decide to be genuine. Steven Warner

The Cordillera of Dreams

The Cordillera of Dreams is the third and final film in the unofficial trilogy directed by Chilean director Patricio Guzmán, preceded by the critically acclaimed Nostalgia for the Light and The Pearl Button. All centered on events during Pinochet’s dictatorship from various points of view, these films use metaphorical elements to speak to the importance of those events and why it’s essential that they not be forgotten. The cordillera metaphor that Guzmán employs here — linking the lingering effects of the nation’s violent coup with traces of past cataclysms in the bedrock of a mountain — doesn’t entirely work. But the film compensates with a large amount of footage of historical protests during the dictatorship, shot by a Guzmán’s friend, who marvels at the technological advances that allow him to fit 1,200 hours of footage in a hard drive, something that would’ve been unthinkable back in the 1980s. Throughout the film, offhand moments confront the horrific past and the marks it leaves on the present, while some particularly sharp talking heads offer insight into the present sorry state of Chilean neoliberal society. Given the existence of two (superior) previous films, it’s in such moments that The Cordillera of Dreams finds its strongest reason for being. Jaime Grijalba Gomez

Kicking the Canon | Film Selection

Kent Jones once wrote that Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne’s 1999 film Rosetta had “a fearsome unity, an unshakable commitment to rendering the contours of a destitute life and the ever present possibility of spiritual transformation.” Indeed, this is an apt description of not just Rosetta alone, but of the Dardennes’ entire body of work — including their 1997 breakthrough, La Promesse. Another Jones quote, this one on Cassavettes, also seems pertinent: “When you look at a close-up in a film by almost anyone else, you’re looking at a representation of the idea of an emotion, no matter how detailed the acting. In Cassavettes, every blink, every shrug, every hesitation counts and drives the story forward.” After years of regional documentary films (plus an earlier narrative film that they’ve essentially disowned), the Dardennes’ La Promesse marked the beginning of the canonical phase of the Dardennes’ career. Filmed entirely in the downtrodden industrial region of Seraing, Belgium, La Promesse follows teenage Igor (a young Jérémie Renier, who would become a Dardenne regular) and his brutish father, Roger (Olivier Gourmet, another actor who was to become a Dardennes favorite). Roger is a slumlord who finds under the table jobs, forged documents, and shoddy lodging for illegal immigrants, forcing them into a sort of indentured servitude as they attempt to pay off their debts to the smugglers. Igor is an eager, willing participant, indulging in petty theft and chain smoking while he collects rent for his father and trawls illicit gambling dens. The fresh faced Renier is clearly modeled after Jean-Pierre Leaud’s playful delinquent in The 400 Blows, an amiable young man who seems to be having fun, with no real context for the harmful system in which he’s participating. When one of the immigrants, Amidou (Rasmane Ouedraogo), falls while working on one of Roger’s illegal construction operations, he begs Igor to watch over his wife and infant son, before succumbing to his injuries. Roger refuses to take Amidou to the hospital, aware that he would be unable to explain what exactly Amidou was doing on the jobsite, or even in the country. Igor is then wracked with guilt, and the remainder of the film involves his navigating of this new, tricky emotional terrain, as he comes to understand that protecting Amidou’s family, or even treating them like human beings, is at odds with the life that he has been leading with his father.

La Promesse sets a template of sorts for all the Dardennes’ mature work: a mobile, constantly roving camera; shooting in extreme close up; brief interludes of characters speeding down roads on mopeds, which act as kind of rhythmic pauses that break-up otherwise unbearably intense emotional action; an emphasis on working class labor, like auto repair or carpentry, accompanied by careful consideration of the exchange of money, i.e. capitalism as a physical action instead of an abstract concept. This film is of course indebted to Robert Bresson’s L’Argent (in much the same way Rosetta owes a debt to Mouchette). Like Bresson, the Dardennes are constantly navigating the region between physical materialism and notions of ‘grace,’ ‘transcendence,’ and a Christian’s concepts of forgiveness. La Promesse begins with an accumulation of quotidian details before gradually revealing the morality tale that lies at its center. All of which is to say that this film represents the beginning of the Dardennes’ ongoing effort to ground the metaphysical in the real, rooting around for the spiritual within an empirical, rationalist framework.

A good amount of that power comes from accessibility: Dardennes films are, first and foremost, crackerjack thrillers. The constantly roving camera is part of it, but so is the filmmakers willingness to begin scenes in medias res, and to use smash cuts. There are no ellipsis, no wipes, and frequently no match cuts — no safe strategies to ease the transitions from moment to moment. The Dardennes will cut in the middle of an action or movement, or immediately following a line of dialogue. Frequently we see an action begin, then a cut to the aftermath of that action. A prime example is Amidou’s death: Igor runs upstairs inside the house to alert him to the incoming labor inspectors, while Amidou is outside on high scaffolding. Igor leans out and speaks to him, then the camera follows Igor as he runs back downstairs, keeping us locked into his perspective. The fall happens offscreen, with a barely perceptible sound effect, before Igor runs outside and sees Amidou’s body on the ground. This monumental action — which will power the rest of the film’s narrative and Igor’s moral awakening — happens in a span of seconds. There is an economy of means here, a race from scene to scene that mirrors the characters’ own increasingly harried lives. They are sprinting towards, desperately grasping at, that ‘everyday grace.’ In the Dardennes’ moral universe, recognizing someone else’s humanity and striving to treat them well is a great victory, a kind of simple victory in the face of an uncaring, impersonal universe. The world can be a cruel, bleak place — the Dardennes’ want to make it just a little bit better. Daniel Gorman