It’s probably (no, definitely) pushing it to suggest that Transformers: Dark of the Moon has anything in common with Terrence Malick’s also-currently-in-theaters The Tree of Life, but that won’t stop me from claiming that the former is sort of the Mirror Universe twin of the latter. Picture Malick’s cosmos-encompassing symphony with an evil mustache, preoccupied with chaotic destruction rather than the order we make out of the universe’s dynamism and fluidity. Put another, just-as-dubious way: The Tree of Life is the story of self-awareness, both that of the universe (or God) and of a young boy as he grows into a man. Transformers 3 has, like its director Michael Bay, no self-awareness whatsoever. Where Malick’s film (and indeed all of his work) is relentlessly searching, examining man’s ego and relationship to nature, Bay’s is merely that ego in its purest, most reptilian form: afraid, angry, cruel, and obnoxious. Malick looks out into space, finds he is not at the center of the universe and is filled with awe. Bay, confronted with the same knowledge, says, “The hell I’m not.”

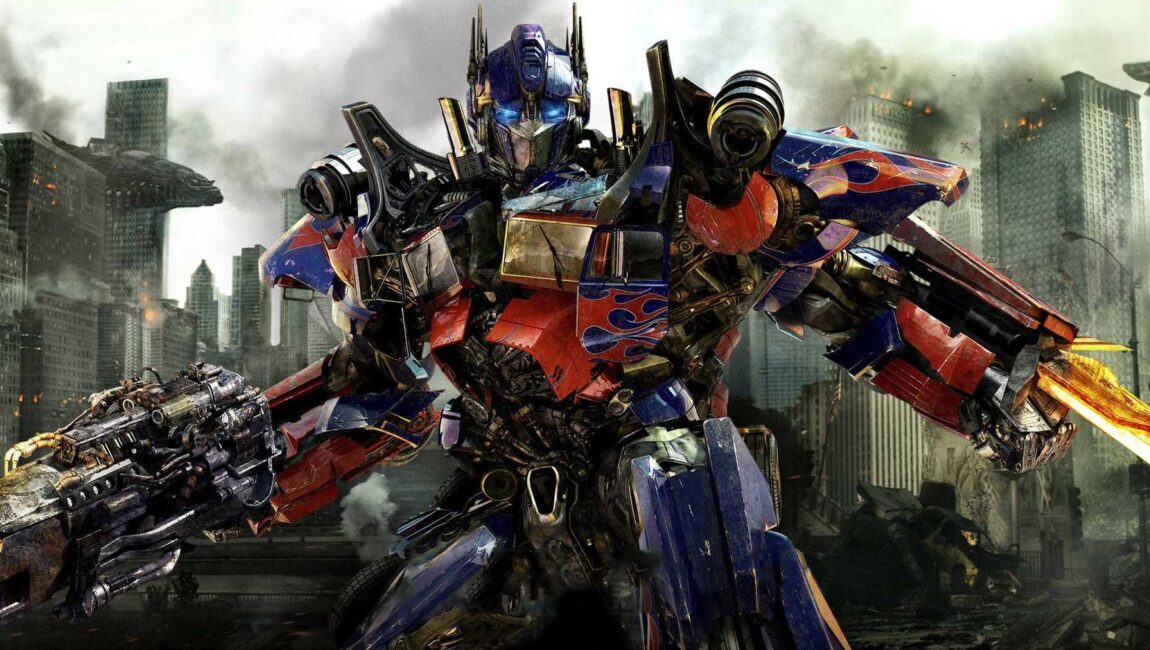

Which, I think, is a perfectly valid point of view for a 300 million dollar toy commercial. Bay’s instincts are exactly aligned with this material: a world without ambiguity, introspection or any modulation of feeling. It’s the world of a child, unaware that he’s shouting all the time in public, that his hackneyed, often nonsensical jokes are terrible, and that he is not the center of the universe. He’s content to play in his sandbox and steal and/or break the neighborhood kids’ toys. Everything is felt and articulated at full volume. Even the films’ protagonist (not remotely heroic though, again, not self-aware enough to be an antihero), Sam Witwicky (Shia LeBeouf), reflects this. Having essentially taken part in one of the greatest events in human history (i.e., the discovery of and communication with an alien intelligence), Sam remains interested only in what this means for him. He whines incessantly about his job (or lack thereof), his crummy car (Bumblebee the Camaro is busy fighting bad guys) and his supposedly insanely hot girlfriend (Rosie Huntington-Whitely, who displays only as much personality as the script asks of her). He barges into a secure government facility with nothing more than a shouted “Don’t you know who I am?!” Of course, his mentor — the Autobot leader Optimus Prime — repeatedly entreats him (and humanity) to “believe in yourself.”

Transformers 3 is guided by an intelligence, it just so happens that this intelligence is, for lack of a better word, evil.

And so we see that Transformers: Dark of the Moon has two messages, the first of which is “Nobody is more important than you. Nothing is more important than how you feel.” The second message is that giant robots fucking up your planet is so cool and you won’t even mind. Bay, at least in the opinion of this writer, is a master of scale and barely organized cacophony; the final 45 minutes of this mammoth monsterpiece comprise a sustained assault on the city of Chicago by massive space robots, and that series of sequences contains some of the most absurdly complex, technically accomplished and amazingly exciting action sequences seen in some time. So dense with activity are these scenes, so massive in scope and so thick with detail that they are practically abstract. Specifically impressive is the way Bay manages to create vertical compositions within the wide scope frame that truly communicate the scale of these events, even if they are narratively confusing. Nobody out there, maybe not even Cameron, is combining practical stunts and pyrotechnics with CGI on this level.

It’s also important to note that there is a sincerely entertaining (and ridiculous) sci-fi action film to be found in this thing. Stripped of an hour of Bay’s positively calamitous sense of humor (gay panic, casual racism, overt sexism: these are the three tenets of Michael Bay’s comedy and without it his films would certainly be considered more acceptable), there’s actually a plot no more or less thin or inscrutable than any mainstream Hollywood summer offering. Whether you’re in any way interested in deciphering it amongst the noise is up to you. At 95 minutes instead of 157, this extreme level of bombast might even be desirable. In the end, all of this amounts to a work that is simultaneously derivative and original, insipid and fascinating. But make no mistake, none of it is an accident. Nobody screwed up. Transformers 3 is guided by an intelligence, it just so happens that this intelligence is, for lack of a better word, evil.