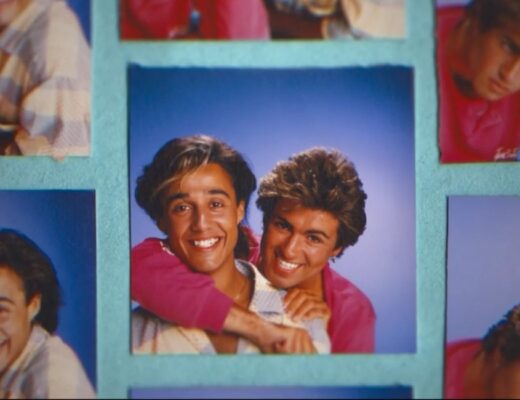

Phoebe Bridgers

At this point, Phoebe Bridgers seems unstoppable. While Punisher is only her second solo studio album, she’s been busy since her 2017 debut Stranger in the Alps: first forming the supergroup boygenius with indie darlings Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker, and then pairing with Conor Oberst for last year’s Better Oblivion Community Center. It’s only natural, then, that Punisher should feel like the ultimate group effort, with writing and performing credits for each of her previous musical partners. The result is a sound that’s remarkably developed for as new an artist as Bridgers. But despite her collaborative tendencies, Punisher is also deeply personal, digging into ideas about her father, her relationships, and herself. These ideas intersect in “Kyoto,” “I wanted to see the world / then I flew over the ocean / and I changed my mind” being the endless need to feel happy in her current location despite feeling unable to enjoy the moment wherever she is. Bridgers even suggests this may be genetic as she speaks of her distant father: “He said you called on his birthday / you were off by like ten days / but you get a few points for trying.”

On this record, Bridgers continues her streak of striking and downright depressing lyrics that never feel like they’re coercing her audience in one way or another. That her words can remain matter-of-fact is evident on both “ICU” (“I hate your mom / I hate it when she opens her mouth / It’s amazing to me /how much you can say / when you don’t know what you’re talking about”) and “Chinese Satellite” (“I want to believe / Instead, I look at the sky and I feel nothing”). But perhaps the most impressive part of the record is the emotional punch packed into the last three songs: “ICU” reflecting on a painful break-up, “Graceland Too” describing an MDMA comedown alongside a self-destructive friend, and “I Know the End” contemplating death and an impending apocalypse. While she may use some fantastic imagery, it’s all of a piece with the despair that one might feel during these disastrous times. But there’s cause for optimism: Through every collaborative project, Phoebe Bridgers has come out stronger than before, and that strength oozes through every track on Punisher. It’s a strong indication that there’s much more to come from her. Andrew Bosma

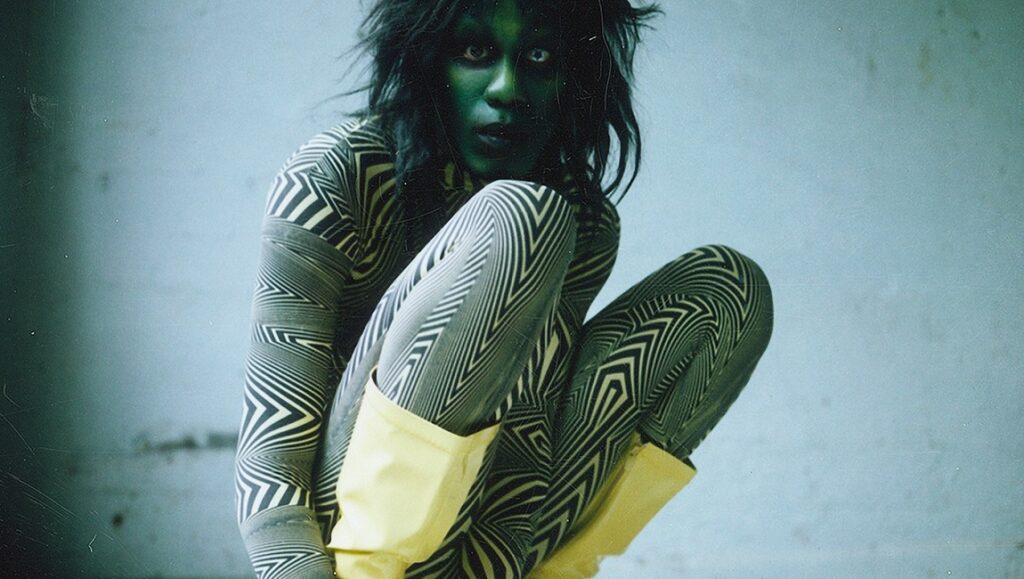

Arca

It’s been a busy last few years for Alejandra Ghersi. In-between investing around three months worth of time into a popular MMORPG, contributing to the soundtrack for Red Dead Redemption 2, and composing the new lobby music for the Museum of Modern Art, she took part in a four-part experimental performance cycle (each “act” was 90 minutes, with the exception of the five-hour-long final movement) titled Mutant;Faith. This combination of new media aesthetics, transgressive gender performativity, and chilly ambiance was nothing new in terms of creative elements for the Venezuelan producer to filter her craft through; if anything, it just underscored how much Arca’s acceptance by the cultural elite never came as much of a surprise, considering the easily transferable nature of her art into the esteemed world of the gallery space.

KiCk i, her latest release, sets out to rectify these notions, distancing the artist from the stark, disorienting compositions of her 2017 self-titled project, and honing in on her more pop-oriented tendencies. This isn’t to suggest there aren’t moments of visceral abrasiveness to be found here — “KLK” finds ways to continually up the ante in terms of deafening bewilderment, with a more than game Rosalía along for the ride — but those moments are few and far between. What one gets instead is a collection of glitched-out tracks that are severely lacking in anything representing ideas, structure or even direction, awkwardly sitting somewhere between noncommittal experimental oddities and completely unmemorable IDM-flavored misfires; they all nearly disappear from one’s thoughts as soon as they end, like cotton candy on the tongue. And the ones that actually manage to stand out usually do so for the wrong reasons. Opener “Nonbinary” features some cringe-worthy, if well-intentioned, rapping on behalf of Ghersi herself, dropping generic flexes like “I don’t give a fuck what you think / You don’t know me / You might owe me / But, bitch, you’ll never know me” to convey her pride in rejecting traditional gender roles, which considering the boldness that’s come before, might be both the tamest and lamest expression of these sentiments Arca has engaged in yet. Paul Attard

Laura Marling

Songs for Our Daughter, Laura Marling’s seventh LP, finds the folk songwriter continuing to explore her femininity, as she did on 2017’s Semper Femina — but here, Marling approaches the subject matter with more focus. Part of this evolution comes from narrowing the scope of her record to address a more specific listener, whereas the previous release played out like a literary collection of different allegorical song narratives, stretching its thematic exploration a tad too broadly. Her new album, instead, unfolds more like a private letter to a younger generation: specifically, her metaphorical daughter, as suggested in the album title. This shifting emphasis towards a more personal angle benefits the music as well, with Marling embracing a more pared-down sound, returning to the humble strums and close-mic’d guitar-pickings of her earlier records. The softer tracks on Songs for Our Daughter beg intimacy from the listener as the singer delicately sings of the wisdom rooted in her personal experiences, while the louder songs here speak to fostering community, music matching theme through a clear embrace of harmonies and inviting melodies.

Marling’s lyrics are ones of shared perseverance: “No one was prepared / but we all performed / like we’d done it all before,” goes one verse in “Blow by Blow,” a stark, piano-led account of a history of resilience. Her words are gently profound, and while they often talk of struggles specific to womanhood, they also refrain from coming off as prescriptive — these are candid observations, their impact building with distance. On tender tracks, such as “Only the Strong” and “Fortune,” dense messages are artfully communicated, with the flow of a casual conversation. Marling’s presence often feels effortless, but she’s also deeply aware of her authority here, consistently mindful of the stakes in choosing the right words — “I write it so I don’t forget / never let it get away/ I keep a picture of you / just to keep you safe,” she sings, as if reminding herself just exactly who she’s singing to and for. Ryo Miyauchi

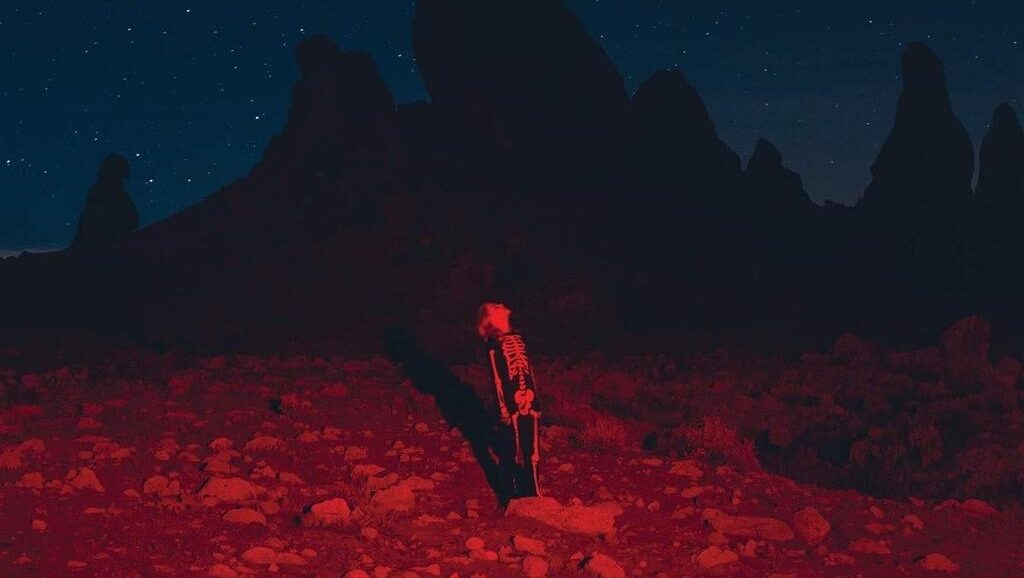

Yves Tumor

It’s hard to imagine an artist reinventing themselves while so successfully achieving a unified goal and message, but this is what Yves Tumor accomplishes on each of their records. In stark contrast to the hypnotic pop sounds of 2018’s Safe in the Hands of Love, this year’s Heaven to a Tortured Mind takes traditionally male-dominated rock beats and solos in fearlessly experimental directions. They create rich soundscapes with bombastic horns and synthesizers alongside lyrics that express the deepest feelings of human desire. Take for example, “Kerosene!,” one of the album’s lead singles, on which Yves Tumor croons “I can be everything, / Tell me what you need, / I can be your baby in real life, sugar,” with Diana Gordon backing, begging for love and affection. “Romanticist” chronicles a desperate search (“I wanna keep you close, right by my side, swear you’ve got me hypnotized … I wanna dance into your hurricane, blinded by your glare again”), and also brings on Kelsey Lu as a guest vocalist, blending two voices into the track’s gorgeous wash of guitars. This lyrical passion is far from subtle, and leans into an open erotic plea for reciprocation. This is apparent not just from the music, but also the album’s accompanying cover artwork, where a tangle of two bodies shimmers in and out of existence, representative of the transient nature of relationships.

Tracks flow in and out of each other, passing seamlessly between desires; a singular voice is present throughout, tying each song to the next. In a world of single-driven releases and albums that can veer too far into the realm of sonic monotony, it’s incredibly refreshing to experience a cohesive work that nonetheless brings a variety of sounds to the table from track to track. Whether it be for quality or brevity, whatever editing choices led to this series of tracks appearing together constitute a work of art in and of itself. Clocking in around 35 minutes, Heaven to a Tortured Mind never overstays its welcome, offering something new at every turn. In a genre dominated by testosterone and misogyny, it’s wonderful to hear something so open and androgynous. And while I’ll miss this particular sound, I look forward to seeing whatever Yves Tumor has to offer when they surely reinvent themselves the next time around. Andrew Bosma

U.S. Girls

Meg Remy understands human struggle. On Heavy Light, the newest U.S. Girls record, she sings a catalog of challenges she’s faced. Tracks like “Born to Lose” (“And I don’t understand things that I’m supposed to do / the postings on the page seem meaningless”) and “Denise, Don’t Wait” (“I don’t think I can make it / another 24 hours from now / I’ll be gone just like some melting snow”) speak to both the depth and gravity of depression taking hold. Others, like “And Yet it Moves” (“Anyone can see the word is stuck / stuck between a flower and a bottle”) and “4 American Dollars” (“No matter how much you get to have / you will still die”), speak more broadly to the toxicity of systemic class challenges. Remy weaves these experiences together with threads of childhood memories, each vocal skit asking about a different facet of these interviewees’ youth. It’s a rich integration, demanding the listener juxtapose the anxieties v. stabilities of juvenescence with those of adulthood, and one that signals her broader thematic concerns.

As much as 2018’s In a Poem Unlimited felt like a clear maturation of the artist’s previous work, Heavy Light demonstrates yet further evolution, a move toward something more collective, connecting the deeply personal to a massive shared experience. At some point, she’s singing not about just her traumas but those shared and bore in an incredibly cruel world. That this album came out a week before lockdowns began across the world situates Remy’s lyrical content as something almost prophetic. “And Yet It Moves” is a reference to the words that Galileo supposedly whispered as he was forced by his government to state that the earth stayed still, a notion of quiet revolution that particularly registers in the current climate of untruth, whether perpetuated by individuals or an institution. All of these admittedly bleak concepts are carried by a series of fresh pop beats that emulate the genre’s sonic textures from the 60s and 70s, Remy’s own bit of resistance and a bubblegum-tinged reminder that even the acknowledgment of tough truth can breed hope. To that point, and despite the finality that the album exudes when speaking of death and the universe exploding, it lands on something less definitive – an insistence that we can change our outcome if we attempt to change our course. As for the Meg Remy, after over a decade of touring and recording, Heavy Light suggests her course is still just getting started. Andrew Bosma