Grimes

Not since Bjork’s 1997 watershed Homogenic has a weird pop artist cast a masterpiece in the mold of Miss Anthropocene: a fusion of progressive sonics, compelling song craft, and high-concept ecological…stuff. It would have been difficult to imagine Grimes pulling this off a decade ago, when she was a true indie artist just breaking through with Visions — an album beholden to obfuscating aesthetics and lo-fi experimentation, set to largely unintelligible lyrics, with the occasionally memorable tune. After 2015’s indelible Art Angels, though, Grimes the Pop Artist became a much more viable idea: Despite dismissing that album as “a piece of crap” almost as soon as she released it, Grimes had in fact managed to balance her eclectic taste with professional (self-)production and sharp writing, a decisive advancement of her craft that also tantalizingly hinted at the many directions in which she could take it. All that Art Angels really lacked — and one assumes this is also why Grimes so quickly soured on her most critically-acclaimed effort to date — was an album-minded sense of cohesion, which admittedly had never been much of an issue with those early albums.

Keep all this in mind and Miss Anthropocene starts to seem like the almost inevitable outcome: This is the best and most ambitious album of Grimes’s career precisely because it indulges in many of her most outlandish musical ideas, but tames them just enough to fit the contours of (adventurous) pop, while giving purpose to its every excess and unapologetic moment of sonic accessibility through a fittingly new-agey theme of dystopian struggle between nature and technocracy. Sprawling and spacey opening salvo “So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth” grinds on for six hypnotically hollow minutes, with thrumming bass lines and industrial noise soundtracking some of Grimes’s most gorgeous (and sensual) vocals. In contrast, the mostly-Mandarin language “Darkseid” (which features Taiwanese rapper Pan, whom Grimes first worked with on Art Angels) and the whirring beat collage of ”4AM” are both breathlessly claustrophobic dance tracks built around agro rhythms and wall-of-sound production dynamics. The pervasive din of dark energy on this album allows for songs like “Delete Forever,” with its bright acoustic guitars and heart-skippingly buoyant melody, to be more galvanizing and surprising than even the poppiest stuff on Art Angels was.

But what really elevates Miss Anthropocene is the assured production throughout; somehow, Grimes’s fantasy-world landscape seems as vivid a space as the technologically advancing Iceland that Bjork and her producers used as a blueprint for the sound of Homogenic. One could argue that earlier Grimes albums like Visions and Geidi Primes tread similar aesthetic terrain; the difference is that the world of Miss Anthropocene actually sounds like a fun place to spend an extended period of time in. As with Homogenic, and its intentional proximity to trip-hop and drum-n-bass, however abrasive and chaotic the production on Miss Anthropocene gets, the songs tend to tether themselves to genre signifiers: “Violence” is the kind of floor-filling European techno rave-up that Lady Gaga might record if her music was as adventurous as her videos, while “Before the Fever” and “New Gods” embrace the unapologetic drama of the power ballad. It’s a testament to Grimes’s musical evolution, though, that this album’s seven-minute finale signifies less any particular genre than a distillation of the sound of an artist who’s starting to create her own: If “So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth” is all tentative uncertainty and gaping negative space, “IDORU” fills that space with euphoric emotion and sonic excess, approximating some hybrid of tropical house, shoegaze, and drone — but let’s just call it Grimes, because it’s hard to imagine anyone else pulling it off. Sam C. Mac

Black Eyed Peas

To put it as eloquently as possible: the Black Eyed Peas are stupid. That’s not a qualitative assessment — the group has consistently produced stuck song bangers over the years, and it isn’t backhanded to say that their brand of plastic party pop is perhaps the definitive sound for a decade of Greek life Saturday nights. But it is a reflection of their conspicuously depthless identity. Lest this begin too critically, let’s establish the undeniable earworm talents of will.i.am as a producer, Fergie’s belting swagger, and…whatever those two other guys do. For over a decade, the quartet produced inconsistent albums littered with guilty-pleasure singles, tracks that pounded you into submission and urged you onto the dancefloor even as their sonic simplicity was resoundingly obvious. It didn’t matter whether the tracks were built on the bouncy 1-2 beat and comic flexing of “My Humps” or the pure electronic, ecstacizing urgency and nostalgic sampling of “The Time (Dirty Bit)” — their unifying factor was an embrace of shallow hedonism and buoyant revelry.

All of that to say, a couple things make a lot of sense with the now Fergie-less Black Eyed Peas’s newest album, Translation: (a) the group continues their sonic evolution (or maybe this is a detour?), from their original trip-pop and then cotton candy EDM to, here, something approximating Latin trap and reggaetron; and (b) while the fellas clearly felt that Taboo’s Mexican heritage offered some sort of coverage, their exceedingly vapid track record makes this latest effort feel like cheap counterfeiting at best and gross appropriation of one of music’s hottest genres at worst. It isn’t like the Black Eyed Peas have ever aspired to much more than common-denominator infectiousness, but it’s a problem that both the production and lyrics are so lazy here. The former offers only the basest interpretation of Latin texture, will.i.am’s distinctive, unevolved bass sounds and rhythms still dominate, and the sampling (which includes an unforgivable interpolation of MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This”) feels less like his work than Flo Rida’s. The latter utilizes a lot of vaguely offensive Spanglish and cultural fetishizing to muster brain-ticklers like “I wanna girl that’s a heater / Caliente, off the meter” (“GIRL LIKE ME”) and “Mami got the fire / and I got the gasolina” (“Mamacita”). This isn’t to say that Translation doesn’t have moments — El Alfa’s reliable speed-spitting energizes “NO MAÑANA,” Becky G shows out on “DURO HARD” and semi-official member and ostensible Fergie replacement J. Rey Soul is often a welcome respite from the album’s oppressing blandness. To their credit, the Peas have assembled a roster of Latin heavyweights here, also including J. Balvin, Ozuna, and Shakira. Decisions like this soften the listener a bit; it all feels too dimwitted to be truly offensive. But by producing something ultimately so unimaginative, the Black Eyed Peas do a disservice to the genre they are supposedly seeking to celebrate. Luke Gorham

Jessie Ware

Jessie Ware nearly called it quits after 2017’s Glasshouse, an album that resulted in an exhausting tour cycle, middling reviews, and slumping sales. Subsequent pressure to push past what she’d previously done put her in a difficult position, but as a last ditch effort to find some creative respite, Ware started a podcast about food with her mom. The result, “Table Manners,” was a huge success, nabbing big name guests like Sam Smith, Ed Sheeran, Sara Bareilles, and many others. What’s Your Pleasure? is the culmination of this de facto creative revitalization, bringing Ware’s confidence and bravado to the fore, while delivering some sick pop beats. More reminiscent of Glasshouse than anything else on the record, album opener “Spotlight” features sparse vocals over a rich, billowing orchestra. Cascading vocals soon follow (”Tell me when I’ll get more than a dream of you / Cause a dream is just a dream and I don’t want to sleep tonight”), and then a classic club beat hits the listener like a freight train, setting the tone for the rest of the tracks.

Throughout, Ware breezes effortlessly through complex vocal lines and thick harmonious chords, layering sounds on top of sounds in a way that can best be described as heavenly. She manages to evoke the Janet Jackson era of club-pop while still retaining her own unique vocal stylings and fills. It takes an immense amount of talent to capture tantalizing emotion in the way Ware manages, but it takes just as much skill to evince reverence for those who came before her while still resolutely pushing the genre forward. Pop is, in many ways, innately intimate, and in a present moment where distance equals safety, it’s especially appealing that this album is so enamored with the concept of touch. Sensual and suggestive, What’s Your Pleasure? feels like a forgotten world, where dim lights, large crowds, and grinding bodies were the norm. As we move towards the end of summer, Ware’s album offers some reassurance that those times may still return. Andrew Bosma

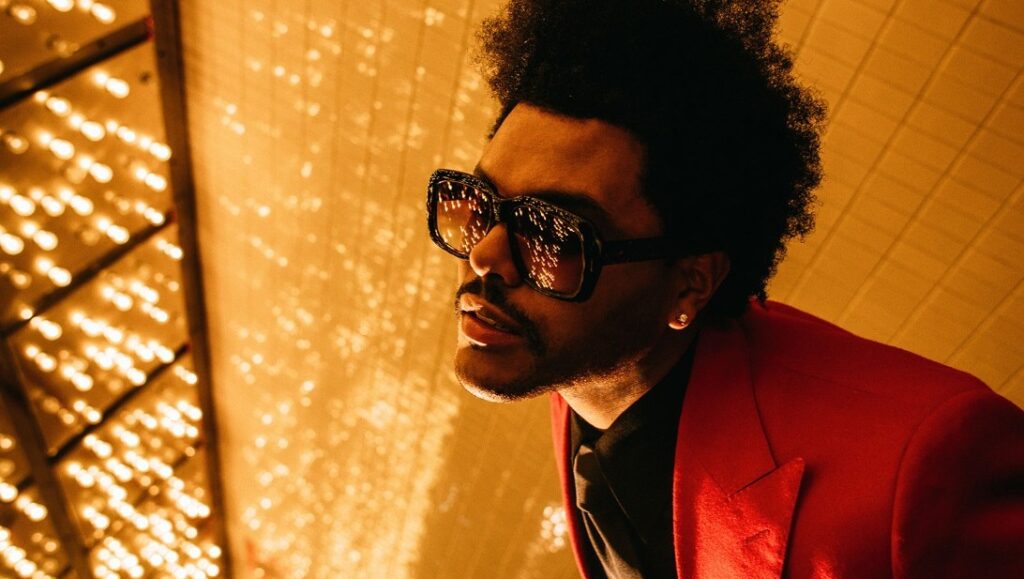

The Weeknd

For the better part of the last decade, Abel Tesfaye has been finding new ways to articulate his carnal desire for drugs, sex, and libertine satisfaction; on After Hours, Tesfaye makes the bold artistic choice to continue expressing his inclinations for these same vices in exactly the same manner — except this time around, he gets Daniel Lopatin of Oneohtrix Point Never fame to produce. That last run-on is a bit of a jape: while it may seem like The Weeknd is up to his usual antics, he’s filtered his intemperance through a faux-framing device of being a narcotized Las Vegas-bound playboy (huge stretch there) who’s on a never-ending, Sisyphean struggle to stay clean and not fuck everything and anything in his path. It’s through this loose concept that he’s able to get away with some of his most apathetically debaucherous writing yet (“She like my futuristic sounds in the new spaceship / Futuristic sex, give her Philip K Dick”) and also feature tracks with incel-friendly titles such as “Save Your Tears.” It would seem, at last, he’s now in on how ridiculous the joke is getting. That, and the added bonus of accounting for the natural conclusions of such affairs (i.e. being left penniless and deserted), gives the music something of an arc; while he’s still not willing to completely play it nice, Tesfaye seems to be maturing modestly enough that it feels reasonable to call this a progressive move for the artist.

What is innovative this time around comes in an adherence to a specific neo-psychedelic audio/visual aesthetic — one that doesn’t allow the album to become the centerless clutter that was Starboy — that often elevates our anti-hero’s haunting falsetto and bad boy antics into the realm of art-pop. “Hardest to Love,” written by the Swedish Billboard-charting God/long-time collaborator Max Martin, flutters through with dynamic drum and bass-heavy production, right before Abel gives what might be his most tender, and yet somehow most Weeknd-y witticism yet: “Together we are so alone.” And when he’s playing to his usual strengths, the astringent bite of the album’s bombastic mid-section (“Heartless,” “Faith,” and “Blinding Lights”) is as equally repellent as it is intoxicating — an indication that while he may have altered his mode of articulation, at heart Abel still is (and probably always will be) the same hedonist. Paul Attard

Fiona Apple

Eight largely reclusive years later and Fiona Apple has delivered her Idler Wheel follow-up. The creation process was a long one, with recording of her new record beginning as far back as 2015. Originally envisioned as a concept album based on her home, Fetch The Bolt Cutters instead became something far more universal; Apple doesn’t just detail her own struggles here, but instead often speaks to the shared pains of a vast humanity.

The first track, “I Want You to Love Me,” clearly demonstrates Apple’s familiar fearlessness, not only when it comes to confronting her love life or external criticism, but even as it relates to her death: “I know that time is elastic / And I know when I go / All my particles disband and disperse.” It’s a power statement to immediately set such a tone, as she goes on to describe harrowing experiences, some of them her own and others not. It’s reflective of a strength that traces back to her childhood, as explored on “Shameika” — “I wasn’t afraid of the bullies / and that’s just made the bullies worse.” On that same track, she also connects this fortitude to her experiences on the road: “Sebastian said I’m a good man in a storm” is a reference to her drummer’s declaration when, after the group was pulled over with weed in their car, Apple hid it on herself. She’s strong in the face of both her depression on “Heavy Balloon — “People like us, we play with a heavy balloon. / We keep it up to keep the devil at bay, / but it always falls way too soon” — and in confronting sexual assault on “For Her” — “Good morning, good morning / You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.”

But Apple thrives as much due to her musicality as her lyrics, and while her piano skills are on full, affecting display throughout, the album’s grandest strength is its percussion. Rich, heavy drum beats mark each track, pushing the album along as if ushering in a parade of traumas. Rather than signaling defeat, these drums represent the sound of survival. Rather than letting experiences shape her, Apple instead attempts to define her own shape through acknowledging them: in an interview with Vulture, the performer noted that it took her a long time to land in this place, and she intends her music to be a celebration of this philosophy. It’s a measure of control that extends to her art, and so while it’s massively impressive to hear an album where every song absolutely works, it’s not a shock that Fiona Apple is the musician who could pull it off in such a meaningful way. Listening to 2012’s The Idler Wheel…,one can hear inklings of this new, inventive sound ready to pounce. As it stands, the end result is one of Apple’s greatest efforts yet. Andrew Bosma

The 1975

With Notes On A Conditional Form, The 1975’s fourth studio album, the British foursome has stretched their established artistry and crafted an album that is their most (self-consciously) experimental yet, for better or worse. NOACF presents a complex soundscape that can be reasonably described as both lovely and drawn out, featuring a runtime of just under 90 minutes, making this their longest album to date. In other words, NOACF is a marathon compared to the standard indie pop album. It begins rather jarringly, an almost-five minute speech from climate change activist Greta Thunberg suddenly followed by the off-kilter, punk-inspired, and generation-specific call-to-action, “People.” After this emphatic opening, The 1975 seem inclined to lean back into their synth-based indie roots, while still attempting to continue the pattern of musical growth borne out across the past three albums. Indeed, many of the standout tracks here, which include “The Birthday Party,” “Guys,” and “Me & You Together Song,” all bask in the softer side of the band’s sonic spectrum.

The lead-up to the album’s release is also noteworthy, reinforcing as it does some familiar charges against the group. In the months prior to NOACF’s release, nearly all of the album’s most striking tracks were released as singles, an unremarkable and expected occurrence – generating interest through an album’s most accessible tunes, enticing listeners to explore a record in its entirety rather than settling for Spotify and radio airplay of select tracks, is a strategy so obvious as to barely merit mention. Except, that is, for the floating criticism decrying The 1975 as a singles band, and their latest album does little to disabuse listeners of this notion: most of the non-single tracks here are relatively forgettable, including some lengthy instrumental interludes, and at the bloated length of NOACF, it’s a reality that may leave plenty of listeners unsatisfied. To its credit, the record is one branded as an experience, and in that regard, it delivers. There’s an indefinable quality to the work, something the group has long aspired toward and which lends it a certain flavor. So while Notes on a Conditional Form does very little to change the narrative, for fans of The 1975’s previous efforts, there are moments here to appreciate, if one is able to muster the stamina. Elliot Rieth

Poppy

Just who even is Poppy? There are a few floating ideas, vague assumptions one can make regarding her character based on a few off-kilter YouTube videos, ones that might suggest her brand of skin-crawling abrasiveness is a decidedly self-aware bit of ironic, post-human baiting. Alternately, a cynical assumption might think that Moriah Rose Pereira-Whitney is just a pretty face for Titanic Sinclair to toy with; he has served as her creative director since the inception of her brand, and it seems reasonable to posit that he might prefer to take credit for all of her success, in the fashion of most jaded men in the music industry. The problem with these suppositions, then, is that it’s difficult to understand the singer according to any one of these narratives by which so many wish to define her; like all human beings, she contains multitudes that exist outside of the realm of instant marketability.

I Disagree serves as her J’accuse to the nay-sayers who would deny her the right to be seen as anything other than her established internet persona. The album is a defiant rebuff of assimilation into any prescribed hegemony, one built on a series of internal contradictions consisting of harsh tonality (heavy metal instrumentation) and soft melodies (the pop orientation of her songwriting). “Bury me six feet deep, cover me in concrete / Turn me into a street” she coos at the start of the record, both an insult and instruction to the many supposed “high-class” listeners — she instead invites a deconstruction of her body, rejecting the imposed confines of its physicality and liberating her from any preconceived notions of who she is and what she’s capable of. And for those with whom she does have specific beef with — notably YouTuber Mars Argo, who sued Poppy and Sinclair in 2018 for copyright claim — this ethos is amplified into serious shade-throwing: “Sorry for what I’ve become / Because I’m becoming someone” and “I’m everything she never was.” Aside from other, more pedestrian insults given on that same monstrous track (“You pray for a reaction”), this might be the most cutting slight on the record, one that both decimates notions of who Poppy is — and establishes who she has yet to become, and asserts her right to control both. Paul Attard