Few debut albums have, since their initial release date, so easily defined themselves as a milestone and game-changer for a genre in the way of In the Court of the Crimson King. The record, released in October 1969 by British outfit King Crimson, is an indisputable masterwork of rock music in general, and more specifically of progressive rock and metal. Even the album’s cover art (beautifully crafted by Barry Godber) anticipates the unsettling vibe King Crimson presents on Court: the image — an illustrated, close-up crimson-colored man’s angst-ridden face, mouth agape as if screaming in horror — recalls nothing so much as Edvard Munch’s The Scream. The record opens with Ian McDonald’s woodwinds and Michael Giles’ drums ushering in the overture of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” a track that works like something of a heavy, distorted riff on a ‘60s TV show soundtrack. And with that bravura entrance, the album’s legacy was written. Accompanied by Peter Sinfield’s prophetic, surreal lyrics — “Cat’s foot iron claw / Neurosurgeons scream for more / At paranoia’s poison door / 21st century schizoid man” — Greg Lake’s scratchy cyborg-like vocals, and Robert Fripp’s frenzied guitar playing built upon odd time signatures, King Crimson introduces a doom-and-gloom atmosphere into prog rock that, to some extent, wasn’t really present before in the work of similar British bands such as Procol Harum and The Moody Blues. It’s a shift that makes sense, as Court is an album as haunted by the socio-political turmoil of the era — “Blood rack, barbed wire / Politicians’ funeral pyre / Innocents raped with napalm fire” — as it is inspired by works of modernist and neoclassicist composers like Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky, and the American free jazz composers (these influences are most apparent in the complex instrumental interludes and outros of King Crimson’s pieces).

But if the ponderous, apocalyptic opening anthem marks King Crimson’s singular style, foregoing as it does the early, familiar psychedelia and blues-rock influences of the genre, their following song, “I Talk to the Wind,” and another, “Moonchild,” are more defined by their English folk-driven melodies and ambiance. More serene than tensive, these two tracks (as their titles vividly suggest) provide, both musically and conceptually, a counterbalance to the album’s blanketing dark mood. Taking the shape of a fairytale and a lullaby, these two songs float on an air of romanticism and mysticism, moving toward a transient, pre-industrialized landscape: it’s an ostensible sad farewell to the “flower power” years — “I talk to the wind / My words are all carried away […] What do I see? / Much confusion, disillusion / All around me” or “She’s a moonchild / Gathering the flowers in a garden / Lovely moonchild / Drifting on the echoes of the hours.” McDonald’s flute work in the first track and his Mellotron in the later, in conjunction with Lake’s soft, velvety vocals, play essential roles in establishing this mood, while Fripp’s tender acoustic and electric guitars and Giles’ somehow soothing drumming enhance and complete the soundscape — and all of this is before the second part of Moonchild kicks in, revealing the band’s sheer virtuosity and eagerness for madcap experimentalism.

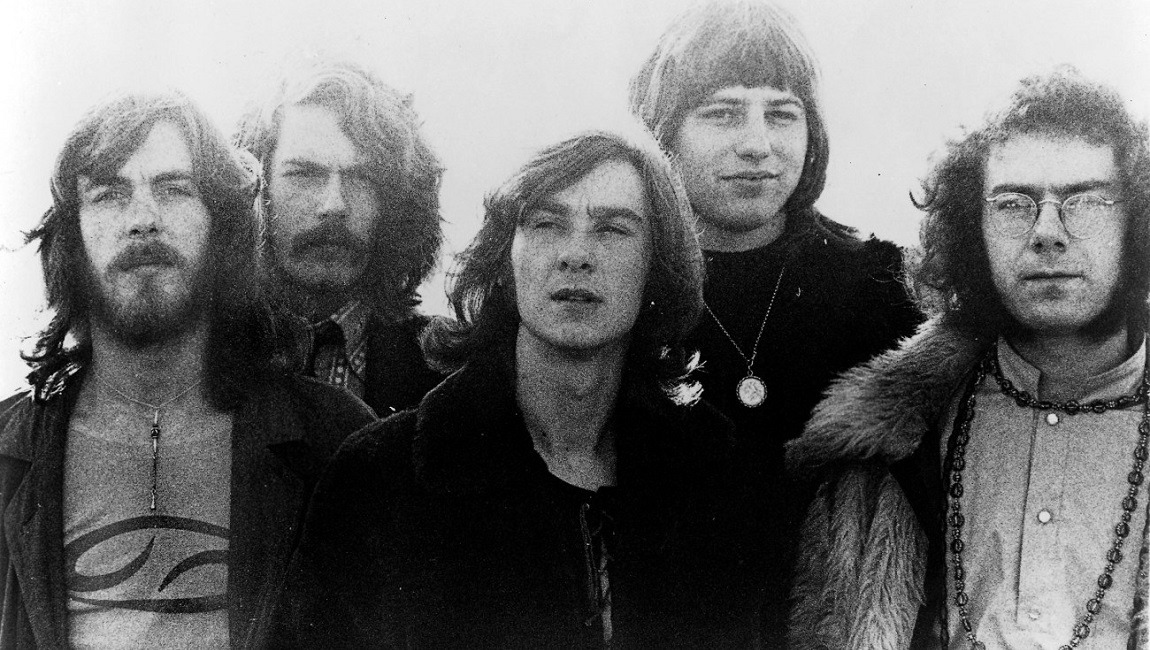

Thus, the third song, Epitaph, should be regarded as a melancholic ballad that bridges the record’s polar forces of delicacy and heaviness. Featuring a much simpler, more straightforward structure, “Epitaph” manifests itself as one of King Crimson’s most memorable and accessible songs, not just on Court but across their career. Here, Sinfield’s ominous lyricism about mankind’s dark future gains full power as it’s coupled with Lake’s passionate, almost tragic vocals — “The wall on which the prophets wrote / Is cracking at the seams / Upon the instruments of death / The sunlight brightly gleams […] Knowledge is a deadly friend / If no one sets the rules / The fate of all mankind, I see / Is in the hands of fools” — and the blend of instrumentation, in perfect harmony, builds a slow-paced, eerie, and absorbing vortex of sound (all as Lake repeatedly sings “Yes I fear, tomorrow I’ll be crying.”) These four songs lead into the eponymous, 10-minute album-closer The Court of the Crimson King, wherein the band once more demonstrates its mastery for composing a multi-layered, orchestrated sonic epic — here, made more transcendental thanks to some backing choral vocals and chanting. Sinfield’s lyrics take a symbolic approach, spinning a medieval-gothic yarn: “The black queen chants the funeral march / The cracked brass bells will ring / To summon back the fire witch / To the court of the crimson king.” This final track is a clear synthesis of what In Court of the Crimson King is: a mix of free-floating inventiveness and uncompromising, rigorous musicianship. Jimi Hendrix, after first seeing them perform live in a London club, once famously dubbed King Crimson “the best band in the world,” and this was months before the group ever released their first record. Since then, the band has gone through many line-up changes (founding mastermind Robert Fripp is the only remaining member), but In the Court of the Crimson King is the rare debut that also proves a magnum opus, laying a rock-solid foundation for the group and delivering a commanding argument that, even five decades on, King Crimson is one of the best rock bands of all time.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.