Life in a Day 2020

Documentaries like Life in a Day 2020 practically cling with desperation to a concept of the universal. Such works insist that there is always substantial, laudable common ground that humanity shares, casting our faults as small obstacles to overcome, nothing that a little peace, love, and understanding can’t solve. In this respect, such thinking feels very much of a more optimistic time, like early 2011, when the first Life in a Day was released. Like its predecessor, the 2020 edition is directed by Kevin Macdonald and compiled from hundreds of thousands of videos commissioned by YouTube, which were filmed by people around the world on the same day: July 25, 2020 (ten years and a day after the first documentary’s day of filming).

Of course, much has changed in the past decade, not to mention the past year, or even the days and weeks leading up to July 25. But in what seems like a concerted effort by Macdonald and his editors, which is at best coddling, at worst actively pernicious, the tumult of the year 2020 and the extraordinary effects of COVID-19 are minimized, only present in sporadic bursts; they exist more as momentary irritants than as the shadow of doom that continues to hang over much of the world. Of course, some locales and nations have only been slightly hampered by the virus, but the fact remains that most of the footage, in public or otherwise, looks as if it could have been shot at any time in the last 15 years, with only the occasional sight of masks marking the specific moment in time that’s of supposedly such paramount importance to this project.

Even more troubling and abject is Life in a Day 2020’s construction. Aside from a few structuring threads, Macdonald is content to organize the film, like its predecessor, according to topics, often conveyed in rapid-fire montages. While these skew universal (and often head-slappingly obvious), like “birth” or “love,” the film moves into genuinely risible territory when it tries to tackle the issues of today, and not just because of the many crowded, unmasked gatherings on display, which makes one wonder how many people must have contracted coronavirus as a direct result of the filming of this documentary. Abandoned spaces and compromised methods of communication due to COVID are contained in a single montage, and the treatment of Black Lives Matter is even worse. All protest footage is relegated to a two-minute sequence, less time than is given to both a proud, anti-mask, MAGA veteran, who gloats over the lack of protests in his suburban neighborhood and proudly shows a letter of commendation signed by former President Trump, and a gleefully vindictive traffic officer handing out tickets on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The whole notion of institutional racism is just another topic to Macdonald, something to be neatly catalogued, unexamined, and forgotten alongside food preparation or, unbelievably, a compilation of oh-so-sick drone shots.

This isn’t to say that it’s impossible for Life in a Day 2020’s concept to be affecting or surprising: in one of two follow-ups from the first film, a mother plays footage of her young son, who died five months before from coronavirus, before moving the camera to show his urn; a Japanese couple breaks up on camera, with the man only belatedly realizing that it wasn’t just an act for the film. But such moments are few and far between, and the effect of Macdonald’s concept is to flatten each individual story, subsuming almost any particulars of individuals or cultures into a banal treacle, fleeing from the most damning moments as soon as possible and otherwise applying its bland inspirational tone without discretion. Naturally, the film ends with a boy speculating about a future humanity where every person’s brain is connected. At this moment, when we are more divided than ever, such a wholehearted endorsement of unthinking unity feels like a slap in the face.

Writer: Ryan Swen

Credit: Johnny Dell’Angelo

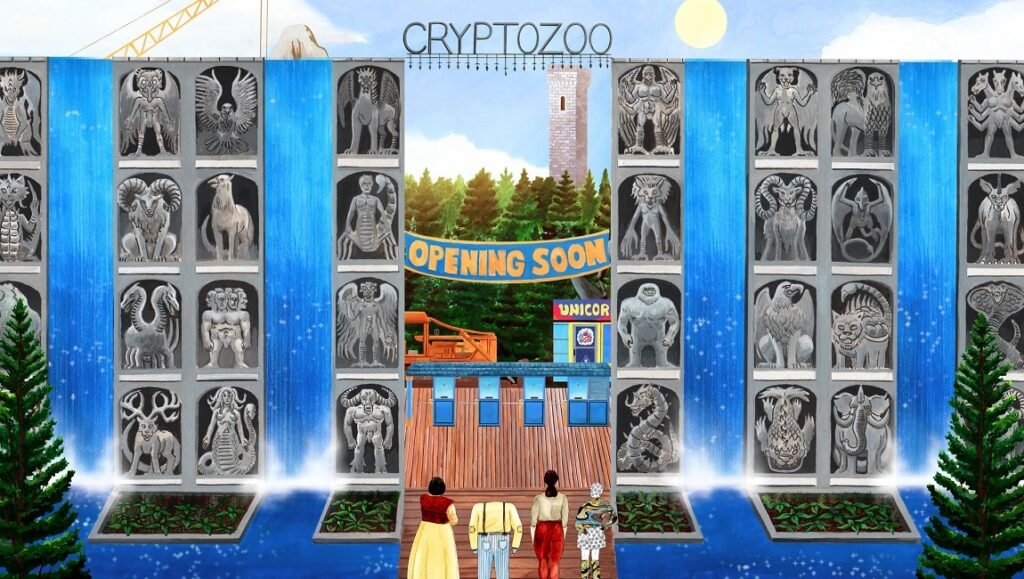

Cryptozoo

In Cryptozoo, artist and animator Dash Shaw concocts an unusual story about cryptids, which, for cryptozoological initiates, are mythical creatures of legend like Bigfoot, El Chupacabra, or the Jersey Devil. But instead of a story about a couple who go into the woods and discover some grotesque animal — the stuff of the film’s opening feint — the film opens up into a rather big adventure following Lauren on her quest to save cryptids from black market captors and place them in a sanctuary called Cryptozoo, which will one day be open to the public. Of particular importance is the Baku, a Japanese dream-eating tapir — it’s the inspiration for the Pokémon Drowzee — that is in danger of falling into the hands of the American government who wish to weaponize it in order to steal the dreams of the counterculture. It might be easy for some to write off Cryptozoo’s Adult Swim-adjacent animation style and deadpan dialogue as simple quirk, but its potent mix of spy and adventure movie tropes, interspersed with thoughtful discussion of zoological ethics, reveals a movie with a lot on its mind, both formally and thematically.

Take, for example, the way Shaw draws humans as messes of wiry linework, their faces changing with every perspective shift. At first glance, these people are deeply strange creations, almost unrecognizable from the animated people who populate other works, and at times even inhuman. But as the film progresses and more of these people pop up and share the screen together, their oddity becomes normalized. The cryptids, on the other hand, are often drawn with much cleaner and geometric linework, most especially the ones furthest from humanoid form. Phoebe, a gorgon, appears human and is drawn similarly to Laura and the others, but under her headscarf, the mess of snakes that makes up her “hair” shares those clean lines with the other cryptids. With this, Dash Shaw’s art here reveals its point: that “normal” is only normal because it is common, and thus the bizarre nature of the cryptids has nothing to do with look, only scarcity.

In fact, this is Laura’s justification for the Cryptozoo as a public good and sanctuary, not simply another zoo: through exposure, the public might come to understand and identify cryptids as normal. But under capitalism and myriad other systemic constraints, it might as well be a theme park for gawking, an objection Phoebe raises time and again. Pliny, a boy whose oversized face is located on his torso, may take joy in receiving a doll of his likeness, but what would it mean for him to sell those same dolls to hordes of tourists who only exoticize his differences? When Laura’s search for the Baku takes her to a strip club, Phoebe draws a parallel, commenting that though many of the women here want to dance, they do so in a system that complicates their choice and agency. Here, too, are Shaw’s artistic choices notable: the strippers are pointedly sketeched in silhouette, as Shaw’s apparent preoccupation with drawing boobs in all other contexts is countered by his refusal to draw anything that could actually be described as erotic leering.

But Cryptozoo isn’t just lessons in sociology. The globe-trotting escapades and grand finale, which unleashes cryptid after cryptid, are compelling both for their frequently psychedelic visuals and the film’s sturdy adventure storytelling. By the time things get bloody, it makes for a genuinely harrowing climax. The film’s thematic concerns are by no means pushed to the side here — if anything, they’re of utmost importance to the mayhem — but what’s most enjoyable in the final act is the surprise of watching the action spectacle overcome an animation style that would not seem to lend itself well to any action at all. It’s as exciting as the third acts from any of the number of the cleaner, more expensive animated movies in recent history, unleashing plenty of pure energy and filmmaking gusto on its way out the door.

Writer: Chris Mello

Wild Indian

Wild Indian begins with an epigraph that reads as parable: “Some time ago…There was an Ojibwe man who got a little sick and wandered West.” It’s the start of an unfinished story — or, as is the case with apologues, many stories — and Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s debut is one possible version. Here, the wandering Ojibwe man is Mawka (Michael Greyeyes), a hugely successful businessman who dons pink polos for golf outings, has a blonde trophy wife (Kate Bosworth) and an immaculate home, and who now goes by the anglicized name Michael. But the root of his sickness begins in the ’80s on an unnamed Native American reservation, where the film’s first quarter takes place. Young Mawka (Phoenix Wilson) is severely abused at home and routinely bullied at school — even his scratchy tenor voice bears a distinct woundedness. Comparatively, his best friend Ted-O (Julian Gopal) seems blessed with a more stable existence, his jovial nonchalance attesting to a presumed lack of familial or social disturbance. Corbine Jr.’s aesthetic approach neatly matches the mixed tenor of these two lives: swirling images of forested beauty, the camera sometimes dipping to ground-level to glide through overgrown prairie grass, are contrasted by the film’s eerie, melancholic drone and strings score. But after Mawka commits a shocking act of violence and the pair agree to stay silent, the film skips ahead roughly 30 years to examine the duo’s dissimilar paths. (It’s interesting to note that while the film mostly abandons its fluid, artful aesthetic after this temporal skip, the score remains the same but takes on a distinctly more sinister feel within the new context.)

Narratively, the film never fully recovers from this jump. Wild Indian proceeds fairly contentedly according to a familiar template: two childhood friends, from different sides of the tracks in their own way, grow into adults fated to very opposite destinies. It does add wrinkles, however, and what keeps such pro forma plotting interesting — insofar as it can be considered interesting — is the film’s refusal to moralize. As these things go, both men are, despite their disparate circumstances, haunted — Ted-O (Chaske Spencer) is just being released from prison while Michael is a self-made man commanding respect — and the causes of their drastic divergence are left implicit. But Michael’s psychological makeup is certainly the most fascinating thing here. A series of escalating scenes — Michael’s manipulation of his own Native identity, his evident consternation when he finds out his wife is expecting another child, his request (and subsequent follow-through) to choke a dancer at a club in exchange for a wad of cash — suggest that his early violence may have lingered and transformed him into an emotionless sadist. But Corbine Jr. recognizes the dead end this predictable development would lead to, and instead continues to complicate the man; we come to see Michael as someone who, more than merely haunted, has also been unfettered by his brush with violence, weaponizing and re-directing its power toward his many successes. The idea that traumatized people continue to perpetuate trauma isn’t a new or particularly interesting idea in its own right, but the way it’s presented here is, as Michael’s small cruelties alternately play out as proactive and reactive: he either seems to be micro-dosing violence or exorcising his latent brutality to stave off something worse.

More interesting, and hinted at throughout, are the metaphorical implications of lingering colonialist violence and cultural warfare with which Native populations must contend, particularly in their pursuit of American success. If we understand the epigraph’s use of “West” to mean western civilization, which seems likely, the film’s psychological and sociological connotations are immense. Unfortunately, such a reading isn’t made obvious outside of the film’s title, and in its absence, Wild Indian is mere character study. It’s at least a consistent and deceptively nuanced portrait of trauma, which Corbine Jr. confirms in the film’s bravura ending. After an inevitable confrontation between the two old friends leaves Ted-O dead and Michael gunshot, and after escaping any accountability for his past actions, an exhausted Michael returns home. His wife asks about the state of his wound, which he then shows her. Her pained face sparks something in him, and he notes, his defenses falling and tears starting to streak, “There’s been worse.” Understanding the significance if not the details, she replies, “It’s awful,” at which he crumbles into her arms. It’s a palliative moment, one that holds an entire life’s pain, in which this man’s sickness is not cured but is at least finally greeted.

Writer: Luke Gorham

Credit: Merkhana Films

Faya Dayi

Programmed as part of Sundance’s World Documentary program, Jessica Beshir’s beguiling Faya Dayi plays less like a traditional non-fiction film than a poetic koan to a part of the world most Westerners know little (or nothing) about. Set amongst the population of Sufi Muslims in the city of Harar in Ethiopia, Faya Dayi uses the khat leaf — a chewable stimulant originally used for religious mediation which has now become Ethiopia’s number one cash crop — as an organizing principle that structures numerous personal testimonials of life in the region. There are no talking head interviews here, nor title cards relaying pertinent information, just a kind of freeform, almost abstract, portraiture. Acting as her own cinematographer, Beshir shoots in smoky black and white, emphasizing closeups of hands and textures and patterns. There are long scenes of people simply at work, first harvesting khat plants from fields, then stripping leaves from stalks, sorting them, then bundling and weighing, and finally taking the produce to markets where it’s sold. All the while there’s a steady stream of voiceover narration that overlaps and flows between speakers as Beshir flits from subject to subject. There are young men planning to immigrate across the sea and who are in the midst of arranging their travels; a woman who recounts a long-lost love; a boy who describes the violent mood swings of his khat addicted father; farmers who explain how their families grew coffee beans for generations before turning to growing khat. There’s a regular undercurrent highlighting the ongoing plight of the Oromo people, who have been targeted and oppressed for decades. Much of this contextual information, though, exists only in the margins of the film, to be gleaned indirectly; Beshir is more interested in creating and sustaining an overwhelming mood of existential ennui. The film has a meditative quality to its storytelling, scenes melding into each other via intuitive connections and associative editing. There’s a sense of trying to capture an entire world here, a way of life that is both beautiful and cruel. There’s pride here, certainly, as one man entreats the young men to stay in their homeland, as they’ll never really belong to another country. But there’s pain, too. Faya Dayi is the best kind of documentary, one that eschews standard, prefabricated forms and instead finds the mesmerizing beauty in the quotidian.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Passing

Based on the 1929 novel of the same name by Nella Larsen, Passing is an auspicious directorial debut for actress Rebecca Hall that follows a pair of mixed-race Black women whose light skin allows them to pass for white. Once high school pals, Irene (Tessa Thompson) and Clare (Ruth Negga) reunite as adults while both passing as white; Irene, married to a darker-skinned Black man (André Holland), uses her ability to pass selectively, usually to gain access to whites-only spaces in 1920s New York, while Clare lives full-time as a white woman, married to a virulently racist white man (Alexander Skarsgård) who has no knowledge of her black ancestry.

Passing as white has historically been used as a survival tool for light-skinned Black people, and Larsen’s novel tackled it head-on at a time when such things were rarely acknowledged. While the idea of the “tragic mulatto” was already something of a racial stereotype at the time, Larsen’s perspective as a woman of mixed race leant a certain verisimilitude to its characters’ plights and turned the stereotype into a kind of cudgel against the assimilative expectations of American society. Hall likewise has unique insight into the material, as she too is of mixed race (her mother has African American heritage), and the film she crafts is a dreamlike examination of race, colorism, and queer desire in America that is occasionally uneven but altogether impossible to ignore. Hall seems to have been birthed as a filmmaker completely in command of her craft — the black and white cinematography and exquisite framing give the film an almost otherworldly, removed quality, as if existing squarely within its characters’ own conflicted psyches. It’s like Irene and Clare are somehow able to escape into an idyllic fantasy world of their own making, upon which the real world, and the ugly realities of racism and America, come crashing.

Passing deftly navigates some tricky waters, tackling a deeply sensitive topic with tremendous grace. And it does so by focusing on the toll of passing on both those who attempt it and on those who cannot; how black identity isn’t something that can be either donned or discarded on a whim, like a costume. Yet it also refuses to judge its characters for their choices — they’re surviving in a very white world, and with passing comes the benefit of white privilege, and the spiritual toll of denying one’s true self. As a white male viewer, it’s difficult to fully understand and appreciate the complexities of the ideas being grappled with here, but it’s easy to note that Hall’s craft is undeniable. The film has a very particular, almost staccato rhythm that feels strangely affected at times, but it’s that very sense of wooziness that makes Passing such a unique achievement. If it occasionally feels unsure of it itself, it’s often because its characters are so unsure of themselves, and Hall dwells in that uncertainty. Thompson’s performance can come across as stiff, until we remember that the character is herself playing a role, meaning that the film is often operating on multiple planes at once. No easy feat, that, especially in one’s debut film, but Hall’s assuredness behind the camera delivers one of the more indelible directorial debuts by an actor in recent memory. Hall has channeled her own experiences (in fact, this film will probably be the first time many people will learn of her Black heritage) into a thorny, lyrical examination of race in America and how internalized racism so powerfully informs self-perception and self-worth. The film’s insularity is both a blessing and a curse, but those internalized emotions just simmering beneath the surface, ultimately, manage to speak volumes. Passing is a cry of anguish, one fully aware that its greatest tragedy is that it cannot sound above a whisper.

Writer: Mattie Lucas

Credit: TIFF

Violation

Writer-director duo Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli have been making provocative short films together since 2017, and with Violation, they’ve finally got a feature-length runtime to expand on their thematic and formal concerns. One of the most discomfiting films of the year, Violation is in some ways a relatively straightforward rape-revenge thriller, albeit one that takes its time digging deeper into trauma and familial discord to complicate that familiarity. If that description brings to mind the dreaded “elevated horror” descriptor, the film at least gives that loaded (and vague) label a good name. Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli patiently introduce their characters and the psychological dynamics at play over the course of a long first act. Sims-Fewer herself plays Miriam, a woman traveling with her longtime partner Caleb (Obi Abili) to visit Miriam’s younger sister Greta (Anna Maguire) and her husband Dylan (Jesse LaVercombe). Greta and Dylan live in a large house in a secluded spot in the woods, which is slowly revealed to be a point of contention between the sisters (Greta seems to have fled from something, although we don’t know what). The group has clearly known each other for a long time, and that shared history comes through in the actors’ easy-going camaraderie between. But soon the seams start to show, and after an abrupt cut the relationship between Miriam and Greta is suddenly infused with tensions and barely concealed recriminations.

This is the first clue that Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli have jumbled up the timeline, with scenes taking place across at least two different summers and two separate visits. Far from being a simple affectation, the fractured narrative instead allows various scenarios to play out as a kind of subjective memory piece. It’s difficult to describe the rest of the film without delving into spoilers, and Violation certainly has a few shocking moments best experienced without forewarning. Suffice it to say, Miriam is raped (a heartstopping moment that manages to be queasily disturbing without being needlessly graphic) and then sets about enacting a very bloody revenge. There’s a long stretch of the film involving the highly detailed, step-by-step disposal of a corpse that made this critic’s stomach churn, even as most of the blood is kept off-screen or shot at oblique angles. But there’s also much more to the film than this: the second half of the narrative maintains the fractured timeline to investigate the assault itself, the events leading up to it, and the emotional fallout that follows. One suspects that most of the conversations around Violation will be about whether the punishment fits the crime; for their part, Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli are very willing to manipulate the viewer’s emotional reaction to each character. Each of the four principals veers from cheerful to menacing over the course of the movie, these shifts matched by the film’s visual beauty, the lush forest setting (shot on location in rural Ontario) simultaneously Edenic and foreboding. Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli employ a stark, minimalist score replete with ominous strings and atonal drones. Even before something bad happens, the mood is ominous, with extreme closeups and strange textures destabilizing the mise-en-scène. What sets Violation apart from the slow-burn, genre-adjacent pictures popularized by A24 and Neon is both its sensitivity to brutally realistic interpersonal dynamics and its willingness to go just a little further than you think it will. (Flipping the script on a typically male-dominated subgenre, the filmmakers include multiple scenes featuring an erect penis.) It’s a stunning debut film, one that pushes past any pat, easy #MeToo discourse and is instead willing to antagonize its audience. [Originally published as part of TIFF 2020 — Dispatch 3.]

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Censor

The opening credits to the new horror film Censor feature a montage of gory and violent scenes courtesy of what the British once referred to as “video nasties,” low-budget horror and exploitation films that trafficked in the offensive and obscene. Those expecting anything quite so nasty, though, should look elsewhere for their kicks, as Censor is in fact quite stingy when delivering the goopy goods, regardless of an intriguing premise that practically begs for such fulfillment. Enid (Niamh Algar), a film censor in ’80s United Kingdom, has never gotten over the disappearance of her younger sister, who went missing while they were playing in the woods as children. When on assignment for a new movie by famed video nasty director Frederick North, Enid can’t help but notice the similarities between the events on screen and those that transpired on the day of her sister’s vanishing. Thus begins Enid’s spiral into madness as she searches for the truth, plagued by guilt and self-doubt. This also signals the first of Censor’s myriad missteps, as director and co-writer Prano Bailey-Bond accelerates that descent to a degree that makes the proceedings borderline absurd: what should have been a slow burn is instead a four-alarm fire, sucking the film of all oxygen and life. Formally, Bailey-Bond displays technical chops, but the movie as a whole favors a cold austerity that at this point has become rote in the indie horror scene. Manipulation of aspect ratios is also a tired cliché that adds nothing thematically to the proceedings, and instead feels like a director simply showing off. This is especially true of the film’s ending, which hints at something meaningful in regards to the blurring of fantasy and reality and the effects of film violence on the viewer, but instead comes across as an obnoxious attempt at cleverness. Censor is indeed nasty, but only for the tedium it inspires within audience members. Rarely has horror felt this inert.

Writer: Steven Warner