Settlers offers neither genre thrills nor any real interrogation of the material’s potentially rich subtext.

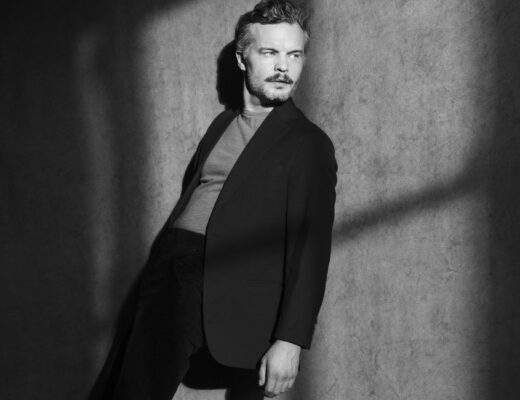

Part sci-fi thriller, part western, part survivalist drama, Wyatt Rockefeller’s Settlers has a lot of familiar genre antecedents, but not much of a clue of what to do with them. In other words, its own high concept — Mars colonists refashioned as Old West pioneers — is the only idea it has, and it runs awfully thin awfully quickly. Divided into three chapters, the film begins with a brief survey of an isolated outpost; there’s father Reza (a near-unrecognizable Jonny Lee Miller), mother Ilsa (Sofia Boutella), and daughter Remmy (The Florida Project’s Brooklynn Prince, as effortlessly charming as ever). They pass the daytime growing crops and tending to their pigs, then studying the constellations and having sing-a-longs at night. Curiously, they wander about outside freely, with none of the usual accoutrement so familiar from other space movies — no zero-atmosphere suits, no oxygen, no pressurized doors, etc. By all appearances a halcyon existence, their routine is interrupted by ominous noises around the compound and Reza’s increasingly jittery nerves. When Remmy awakens one morning to the word “LEAVE” written in blood across their windows, all hell breaks loose. Intruders assault the compound, but after fending off this initial wave, Reza is killed by Jerry (Ismael Cruz Córdova). Jerry claims that the compound actually belonged to his parents, and that Reza and Ilsa stole it, banishing him as a child in the process. Now, he’s come to reclaim what’s rightfully his. Chapter two details a new, volatile dynamic, as Jerry allows Reza and Remmy to stay with him and get the compound back up in working order. Córdova is an intense onscreen presence, speaking calmly and seemingly with benevolence, but with something ominous behind his piercing eyes. It’s particularly alarming when he lays hands on Ilsa, who tentatively acquiesces to his romantic overtures, much to Remmy’s horror. She runs away and makes a startling discovery about the place where they live, while Jerry tells her cryptic tales about the dangers that lay beyond the boundaries of their home and the generations of terraforming undone by strife.

To disclose much more of the story would not only constitute spoilers, but also take up very little space. Nothing much happens in the glacially-paced Settlers, which emphasizes mood and ambiance over story mechanics. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but this world is so vague, so barely fleshed out, that there’s nothing to really grab ahold of. Jerry’s story of being driven from his birth home suggests a kind of “return of the oppressed” subtext, but it’s never developed beyond simple, broad strokes. In keeping with the film’s nods to the Western genre, Reza and Ilsa could be stand-ins for manifest destiny colonizers, which in turn would suggest that Jerry represents displaced indigenous peoples. But this isn’t developed much either, the film instead focusing solely on whether or not Jerry represents a threat to Ilsa and Remmy. That question is definitively answered in chapter three of the film, which casts Nell Tiger Free as a now decade-older version of Remmy, who has been contemplating escape for some time. Rather than delving even obliquely into the sticky matter of America’s racist, genocidal past (certainly fruitful, and timely, material), the film floats the deeply unpleasant specter of potential sexual assault over the proceedings, an old genre trope one might’ve thought we were done with at this point. Settlers is well-made, and the cast is as good as they can be, but there’s nothing of actual substance here. It’s hard to shake the impression that Settlers is a rough draft of a better, more thoughtful work.

Originally published as part of Tribeca Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 6.