Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis delivers what’s expected: thrillingly pure exhibitionism for its own sake, the kind of massively scaled contemporary blockbuster in too short supply in our MCU era.

Much like his previous modernization of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis is, on its surface, empty spectacle thematically concerned with a rather specific breed of American excess located and perpetuated within this country’s cultural iconography — so much so that the slovenliness spills out into every conceivable aesthetic direction. Take your pick: the messy, disorganized screenplay that has little regard for temporal logic; the frantic, almost plastic-like, digital-sheen visuals; the manically dense montage that feels like you’re high on sugar at a big top carnival; the editing rhythms that seem to be non-existent with how inelegant and often illegible the images appear once assembled; the chintzy modern-day needle drops (including an original song by Eminem, a white artist popular in a Black genre paying homage to the original culture vulture); and, of course, the non-stop crescendoing from one big set-piece into the next, like the film’s trying to run a marathon. Even with the noticeable bloat, it’s often thrilling, but also exhausting, usually at the exact same time, and so boredom can never really set in. In short, it’s a Baz Luhrmann picture, bearing all of the baggage and pleasures that come with that headline.

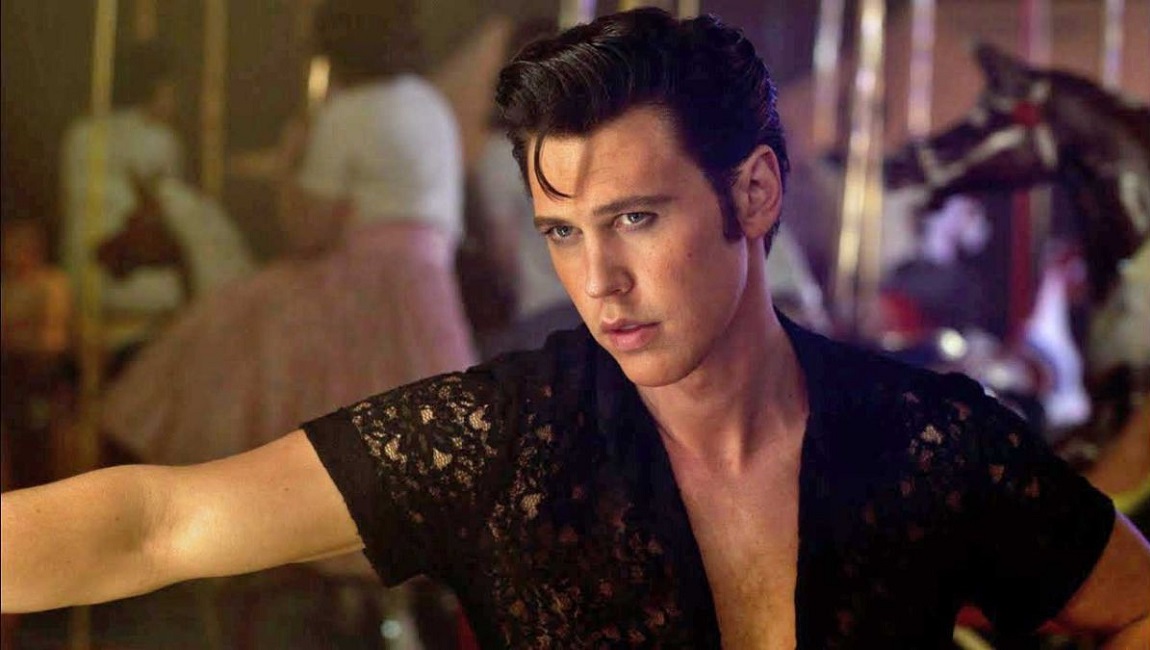

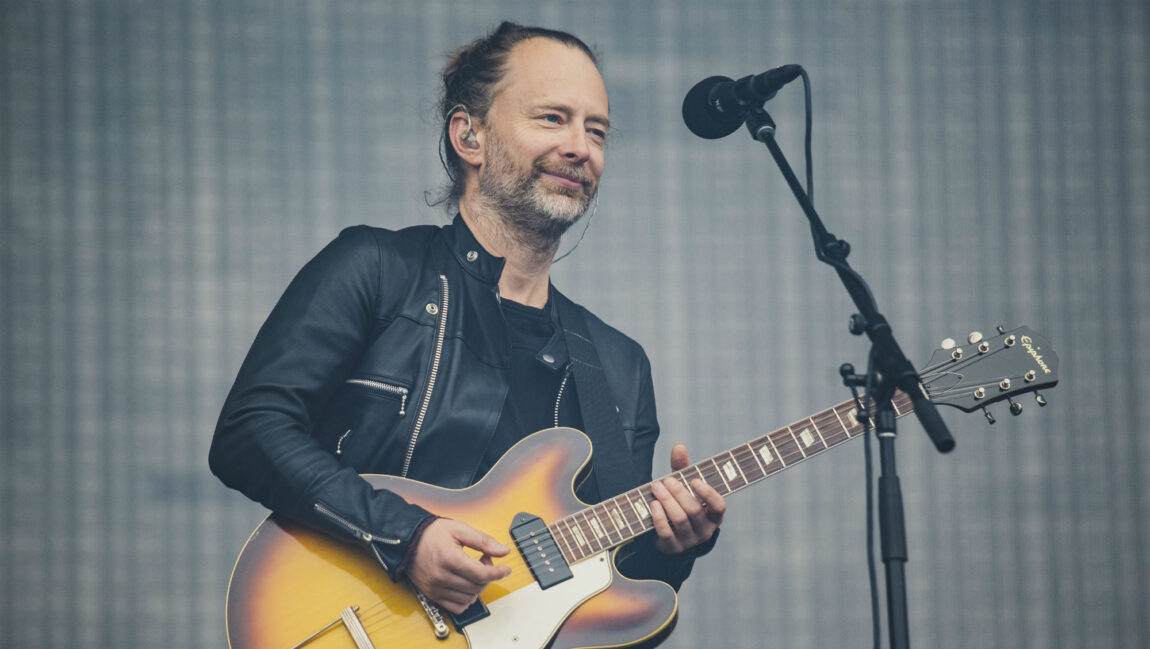

Yet, instead of adapting the so-called Great American Novel this time around, Lurhmann and his three other credited co-writers have been tasked with dramatizing the first Great American Rock Icon who wasn’t named Chuck Berry or Little Richard: here, Elvis is conceived of in the same mystic, hushed tones as Jay Gatsby, an inscrutable figure gazed upon and idolized from afar, one who himself is chasing something the entire world can seemingly never deduce. His motivations and intentions are left purposely opaque, as Luhrmann’s never been one for psychological depth — though, there are an amusing number of Freudian undertones that emerge once his mother dies — except at a few clunky junctures where he turns into a woke whiteboy and the film feels the need to spell out his appreciation for the Black musicians he stole from, or shed a single tear for a slain MLK Jr., which, considering the narrative perspective the film assumes — that of Elvis’ nefarious manager Colonel Tom Parker, played by a too eager Tom Hanks, caked-up in purposely gaudy prosthetics — the nebulous nature of Elvis’ worldview makes sense: his image has become so detached from any semblance of humanity that declarations such as “personal convictions” become afterthoughts. Besides, these are all minute details anyway: Elvis doesn’t position itself as being historically accurate either, instead choosing to engage in pure exhibitionism for its own sake — there’s an attempted stab at mythic deconstruction by the end, but the film’s a tad too enamored with itself to ever say anything too self-critical. Regardless of its qualitative merits (which are, of course, the most perfunctory qualities of the picture: Butler, the sound design, a pretty alright Doja Cat track), there’s an intensity to the vision here that feels all too lacking in contemporary blockbusters of this size and scale. Fuck it: let’s just call This Baz’s Malcolm X.