Light Matter’s fourth 2023 program is titled “Blurred Lines.” Though lines literal and figurative blur within many of the constituent films, the title refers more to the blurring of the boundaries of film and art brought on by the propagation of machine learning. Though not all of the technologies with which the program’s artists interface are nearly as arcane as systems like ChatGPT or Midjourney that have provoked over the last year or so, even festival mainstays like Victoria Schmid and Blake Williams — the latter of whom’s 3D film Laberint Sequences, which finishes the program, InRO covered earlier this year — mediate the image as captured by their cameras in some way.

The program begins with ‘PROTOTIPO, a recording of a live collaboration between artist Tina Frank and musical duo General Magic, which isn’t so different from the visualization you might have seen 15 years ago in iTunes or Windows Media Player. The piece holds more visual interest than that — the side-by-side images (perhaps the result of collapsing two channels into one) feature a more compelling mix of forms, light, and color, oscillating more erratically and more distinctly matched to the percussive soundtrack, a mix of live drums and digital clipping/noise. But on its own, it might not feel like much more than the excerpt from a larger performance, which it presumably is, transposed into a cinema. It sets both a tone and a mission for this program, however, in featuring a more traditional generative artistic practice, one through which the boundaries of art were resolved decades ago.

Nini Korkalo’s The Best Lover is a bit of a swerve, its new age bent as striking as it is quaint. The film begins with a guided meditation over a black screen, giving way to a montage composed mostly of stock footage of animals and landscapes. To make eye contact with another being, even with the remove of projection, of the generic origin of the footage is a direct experience rarely matched within the program. Once the screenplay kicks in, the film features three characters: the Therapist, represented by a forest; the Collective Mind, a swirling galaxy; and a retired Barbarella, portrayed in a live-action performance (again, rare for this program of films!) by Sari Lilliestierna. In a dialogue between the first two characters on love, the perspective of the latter ties most into the program’s themes, processing through available definitions of love as a machine learning model might. Korkalo’s film, though, is still largely grounded in the organic, an anchor that is ripped out as the program progresses.

The next film, Mandy Eugeniou’s KOMPROMAT, makes very different use of stock footage — or, more precisely, the Commons — from which its “orphaned and ‘poor’ images” are exclusively taken. Mundane shots — of cats being cats, of food being chopped — are abstracted by cutting, pixelization, and zooming. Eugeniou’s narration doesn’t isn’t any clearer than the images. Sometimes, it seems as though she’s commenting on the images themselves, and sometimes on her film (chopped to pieces like the peppers or tofu within); or perhaps this lack of clarity is itself the comment. KOMPROMAT is alienating in its obscurity, but also distinctly human. Words and images may be employed in a manner detached from their meanings, placed together in ways that further elide meaning, but they were placed; by a human voice, by recognizable modes of editing. Perhaps this is a humanist reclamation of the unsettling babble we’ve seen produced by machine learning.

Victoria Schmid’s NYC RGB is perhaps the most traditional “experimental film” in the program, and also is quite fitting for this particular festival as it most literally and creatively takes light as its material. Filmed in a New York City apartment, each shot was conducted in sequence with red, green, and blue filters, such that static subjects appear in full color, but anything that moves appears monochrome. Smoke drifts in three different directions, shadows overlap into distinct secondary colors, and clouds dissolve into a ripple of hues, all while phantom cars and people travel the street. The effect is gorgeous; having first viewed this film at TIFF earlier this autumn, it was a pleasure for this writer to see it again, the work seemingly lending itself to new discoveries with each subsequent viewing. NYC RBG reflects the process we see throughout the program at its most natural scale: the reconstruction of dispersed images.

Michael Mersereau’s Haxan: Reducida evokes traditional film only notionally, as an abridged recreation of the 1922 film Häxan, juxtaposing more “poor” images with machine-generated video. This isn’t the first film in the program to make use of that technology; two of the included films feature “A.I.” (a term it’s otherwise best to avoid so as not to contribute to the stark weakening of its definition) in their titles. If the goal here is blurring, the film mostly falls short. It’s clear which images are machine-generated — with one distinct exception: a diving board wiggling over a backdrop with the same color and texture, paralleling the unnatural wiggling often generated by computers. Perhaps this “failure,” though, is fitting for a remake of a documentary about witchcraft, and one machine-generated sequence in which a humanoid figure rises out of a non-existent chair, which itself recedes into the background, is particularly striking.

In Lilan Yang’s The Perfect Human, another reimagining of an older film, this time Jørgen Leth’s 1968 film of the same title, lack of clarity reaches a peak. The quasi-pointillist animation brings to mind a zoomed-in newspaper or comic image, but it’s initially unclear if this is the result of traditional animation, rotoscoping, or some type of machine-learning generation or post-processing. Some of the animations do more clearly bear a live-action source, but Yang’s artist statement suggests the film was created through a hodgepodge of methods. Here, traditional and new filmmaking methods are successfully blurred. The film’s voiceover eventually falls victim to a similar crisis of identity when it exits recognizable English. Is this another language, perhaps Danish in deference to Leth? Or is this nonsense? If it’s nonsense, is it human improvisation or red room-adjacent post-processing? Or is the voiceover machine-generated as well? Perhaps the perfect human is no human at all.

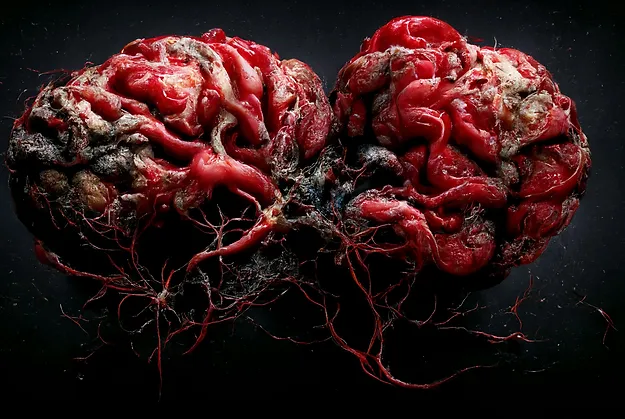

The tenor of peak reached in Ian Haig’s AI Lobotomy is one of unpleasantness. A percussive score even louder and even less organic than that of ‘PROTOTIPO overlays a rapid succession of presumably machine-generated and frequently grotesque brains. According to program notes, the title refers to a “hypothetical scenario where an AI system is deliberately limited or ‘lobotomized’ in terms of its cognitive abilities in order to prevent it from developing consciousness or becoming a threat to human beings,” and we’re clearly not seeing a desirable scenario. Alex Broadwell’s Refuse 2 (Disc) returns to digital obfuscation, but this time in the familiar form of the artifacts of a damaged DVD, while Sarah Ballard’s to be with you (grotto) takes advantage of both digital and film (finally more 16mm) artifacts in order to obfuscate both images and written language before the program ends with Williams’ aforementioned and inventive film.

Perhaps the elephant in the room here is the ethical debate over machine learning, particularly the objections that have been raised by artists whose work was used without permission. Sometimes, it feels like this issue can be elided by pointing out that despite all this input, machines are still outputting untenable images and language, but here, that’s often the point. And then there’s the elision on the other side, that these machine learning models are here and can’t be put back in the box (absent a lobotomy); thus, any existential debate is moot. Without staking out a “pro-AI” position, this program exists more in this latter space, exploring the technology as it exists and contrasting it with other technologies, new and old, used by experimental filmmakers. Its discursive function is as an invitation, expressing both caution — with The Perfect Human in particular as a centerpiece of ambivalence — and excitement as we look toward the future of experimental film.