Writing about Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus is a challenge, not least because of its stark minimalism. I can’t recall a concert film as ascetically committed to documenting little more than the intimate dynamic between a musician and their instrument. Produced six months before the iconic composer died of cancer, this final performance encompasses a 20-song setlist of staples and obscurities spanning Sakamoto’s discography. But director Neo Sora imprints a distinct aesthetic that alternately valorizes and humanizes his father’s incomparable musical mastery.

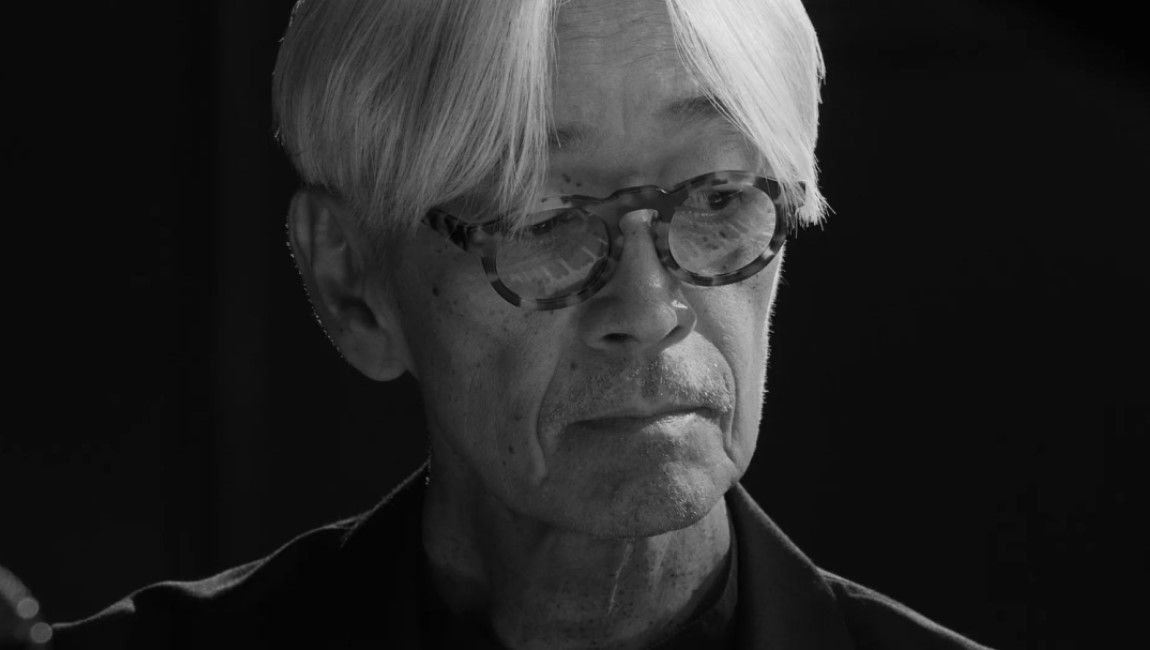

Sora and Sakamoto worked closely together in constructing the film, recording and organizing demos of the music the latter would play in the NHK Broadcast Center’s 509 Studio. Yet Sakamoto largely remains the sole human figure onscreen, the camera gliding around a grand piano ensconced by microphone stands. As one song blends into the next, the cumulative effect resembles the overriding emphasis on labor in Slow Cinema. Indeed, Sakamoto rarely pauses for long between songs, his soft breathing faintly heard beneath the swell of the piano. But the intense concentration on his expressive face counters the seeming effortlessness of his skill.

Labor is subtly alluded to in the panoply of wires snaking through the studio and made abundantly evident when Sakamoto makes a mistake, only to regain his composure. The poignant spectacle of watching him perform songs, old and new, is matched only by the film’s ostensible intermission when Sakamoto asks for a break. Mortality distinguishes our accomplishments by reminding us how flaws can be more revealing than impeccable craftsmanship. Sakamoto retains his dignity by refusing to occlude his imperfections, and, in the process, repurposes the cancer that would kill him into part of his performance.

Sora’s camera rarely veers from his father as DoP Bill Kirstein’s monochromatic digital photography accentuates the diurnal lighting that gradually casts Sakamoto in near-total darkness. In subject and tone, the film brings to mind Agnès Varda’s Jacquot de Nantes, which, as Andrew Winthrop notes in his superb essay, is also concerned with “someone lost, who was not lost at the time of filming.” Remarking upon the haptic close-ups in that film of Jacques Demy’s face, Winthrop described the “haptic viewing experience” as one that “often involves a degree of work for the viewer, regularly incorporating specific interpersonal notions or experiences.”

Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus achieves a similar phenomenological effect as light and shadow subtly morph the composer’s gaunt features and slender fingers. Watching Sakamoto play arpeggios, I was reminded of my own father playing the piano and subsequently seized with emotion. This empathic recognition of Sora’s haptic engagement with his father through his camera only enriched my appreciation for the artistic equilibrium achieved between both filmmaker and subject.

As a layperson in music criticism, this writer can only provide minimal insight into Sakamoto’s technical acuity or compositional versatility. Fans will doubtless recognize the symbolic placement of songs like “Happy End” and “Tong Poo,” first performed by the Yellow Magic Orchestra, at the tail end of the concert. Sakamoto was famously ambivalent about being thrust into the limelight by his work with the influential band, but the prominent appearance of those songs indicates an acceptance of that part of his legacy. By arranging his pop songs and film scores for one instrument, Sakamoto grants them equal significance within his corpus, though the climactic performance of his theme from Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is admittedly emotionally overwhelming.

Does anyone need to know all of this before seeing Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus? In some respects, it helps somewhat deepen one’s appreciation of the film as a distillation of an astonishing career. Yet without that knowledge, the film’s dialectical illustration of Sora’s and Sakamoto’s respective mediums remains a tremendously moving testament to making art as a form of expressing love. Sparsely recurring shots of negative space without Sakamoto anticipate the film’s final moments, which I dare not spoil. Yet their simple intimation of the work that remains is inextricably linked to the lingering traces of the artist in their tireless movement toward grace.

DIRECTOR: Neo Sora; DISTRIBUTOR: Janus Films; IN THEATERS: March 15; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 43 min.

Originally published as part of InRO’s NYFF 2023 coverage.