Our sixth dispatch from the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival (here’s our first, our second, our third, our fourth, our fifth) offers an eclectic mix of takes: Terrence Malick’s return to more pastoral vistas, A Hidden Life; Venice award-winner Atlantis; Ken Loach’s latest social lambast, Sorry We Missed You; Benedict Andrew’s micro-biopic of the titular starlet, Seberg; and another four, more under-the-radar films of varying success — Pema Tseden’s Jinpa follow-up, Balloon; micro-budget sci-fier, The Vast of Night; Gael Garcia Bernal’s second directorial effort, Chicuarotes; and a collaboration of Canadian directors, The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open. Our final TIFF dispatch will run Friday, and will offers takes on all twelve features from the festival’s Wavelengths program (dedicated avant-garde and adjacent cinema).

A Hidden Life

From its title alone, Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life concerns itself with subjects that cinema often struggles to depict: the twin blossomings of consciousness and conscience. In telling the story of Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl), an Austrian farmer and conscientious objector during the time of the Third Reich, the notoriously reticent American director has returned to the histories of his pre-Tree of Life period, even opening with archival footage of a Nazi rally. But this vision of breathtaking natural expanses and solid manmade enclosures remains every bit as formally radical as any of his films this decade. Time flows ever-forward, moving Franz from a life of contentment in the alpen heights of St. Radegund, to the prisons of Berlin-Tegel, where he awaits his final verdict. And yet, A Hidden Life — previously titled Radegund — remains, per its title, startlingly interior, unfolding as an essentially epistolary work, with nary a full, back-and-forth conversation over its 173 minutes. The story of Franz’s romance with his wife Franziska (Valerie Pachner) plays out in a flurry of glances and charged edits, set to Pachner’s hushed voiceover; Franz’s eventual departure for the city, which is accompanied by black-and-white train footage, is set to narration about a recurring nightmare. No doubt some will say that refusing to externalize Franz’s unwavering decision renders the film beatific in the extreme — but can one really assume that his silence indicates an absence of doubt, or that Malick’s view is one of uncomplicated approbation? Indeed, what A Hidden Life ultimately evokes is belief as a state of constant affirmation — which perhaps remains beyond what even cinema can capture. Only when the images stop flowing do we fully ponder the unseen; only at this film’s end, through an epigraph as moving as one is liable to encounter anywhere, do we feel the overwhelming weight of a life lived with conviction. Lawrence Garcia

The Vast of Night

The Vast of Night opens with an assured and prefatory walk-and-talk, an extended tracking shot that first follows first Everett (Jake Horowitz), a local radio show host, and then adds Fay (Sierra McCormick), a student and switchboard operator — both young residents of 1950s Cayuga, NM. Not only does this formal choice introduce us to the principals (he, a quick and slick charmer, preternaturally professional and with ambition to burn; she, a techno geek, thumbing science magazines for fun and keenly aware of her oddball status), but it also orients to a specific place and time. The pair wanders in this unbroken shot and the camera pursues, as the town’s compact geography and mood begin to clarify. Our starting point is the school gymnasium, the bleachers riotous in the wake of the basketball season’s first game, colorful residents,descending upon the meager evening entertainment. Everett and Fay exit the din and pomp of pre-game revelry for the headlight-lit parking lot, and eventually the small town city streets, empty beneath a sky dense with dark in an era absent of light pollution. The Vast of Night is also genre fare, a context signaled immediately – debut director Andrew Patterson situates his film as a Twilight Zone riff, only here titled Paradox Theater, and The Vast of Night is presented as an ostensible episode. Opening to the image of an old-timey cathode-ray tube television, all rounded edges and wood panel trim, the camera then proceeds to zoom and colorize and unfuzz, passing into the tv, so to speak, and commencing the film in earnest. This entire set up, and the actors who sell it, demonstrates a remarkable confidence: Patterson saturates his visuals with period-specific flourishes, and prizes specificity (the culturally-bred stoicism of women, the risk of giving voice to black men on the radio) without ever descending into cheap nostalgia. The Vast of Night’s influences and touchstones — H.G. Wells, Rod Serling, Roswell lore, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Red Scare propaganda – are varyingly inter-, extra-, and subtextual, both interacting with existing material and subverting familiar expectations. But this is micro-budget cinema, something reminiscent of a lo-fi Stranger Things by way of Primer, and Patterson’s greatest trick, in defiance of budgetary limitations, is to perfect the movement and manner of his film’s kinetic action: both the blocking and choreography are consistently striking, and exhibit a theatrical understanding of the veritable stage, and the clear standout sequence is built on a prolonged medium-closeup of a switchboard, Fay’s movements and mindset increasingly frenetic even as she artfully manages the patches and plugs with something of balletic grace. Patterson integrates these spurts of deceptive, practical complexity into patient long takes, a strategy which forces viewers to recondition the modes in which they movie-watch, developing and trusting the character dynamism and intensely purposeful mise en scene rather than getting bogged down in any rehash of cockamamie alien chestnuts. A return to the represented era’s understanding of science fiction as a genre built on disquiet, and the intrusion of the unknown, The Vast of Night does not just upend its minimalist genesis, but also subsumes its spirit — and in the service of creating something grand from its well-worn parts. Luke Gorham

Atlantis

With Atlantis, director Valentyn Vasyanovych (also editor and cinematographer here) has created a dystopian nightmare out of the Ukraine’s current political and social quagmire with Russia. Like some kind of unholy amalgamation of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Sergei Loznitsa’s 2018 film Donbass, Atlantis imagines a futuristic, liberated Ukraine that nevertheless is in ruins. Huge swathes of land are uninhabitable, drinking water is scarce, and bombed-out factories litter the landscape (any similarities to Chernobyl are clearly intended). Of course, part of Vasyanovych’s point here is that, despite the vague sci-fi genre trappings, things don’t look that different from the normal stages of late capitalism (even more intriguing? The notion that this nod towards speculative fiction gives the film, and filmmaker, some cover from government meddling. Regardless, Mad Max Fury Road this is not). Atlantis consists of 28 individual scenes, each a discrete unit separated by a hard edit (with one exception involving an uncharacteristically gentle dissolve). By my count, 5 of these scenes involve camera movement of some sort; otherwise, the compositions are locked down master shots, with a shallow depth of field that creates a kind of large-scale tableau. It’s a disturbing distancing effect, as we watch Serhiy (Andrii Rymaruk), a former soldier dealing with PTSD, first working at a huge metal refinery and then taking to the road to deliver potable water to areas affected by the war. Along the way, we gradually learn a few scattered details about what has happened. But traditional plotting isn’t particularly important here. Serhiy eventually meets Katya (Liudmyla Bileka), an archaeologist who now volunteers with an organization that digs up, and identifies, bodies of soldiers who were left behind enemy lines during conflict. In her words, she is giving the families of these men closure, allowing the war to finally end for them. The great lost city of Atlantis has been part of the popular imagination for centuries; here, the myth is reconfigured to suggest a kind of subterranean society that exists just below the surface, a world of corpses, victims of torture and other atrocities. As we watch several scenes of graphic autopsies unfold, in real time, it becomes clear that Vasyanovych is interested in a moral reckoning of sorts, a clear-eyed confrontation with the past. The first scene of the film is an overhead view of three figures beating someone to death, and burying them. It’s filmed in infrared, obscuring the more grisly details and turning bodies into ghastly digital artifacts; the overhead position suggests a god’s-eye view, or a drone or satellite (or an implied audience). The end of the film is shot in the same way, as Serhiy and Katya embrace. By imposing the same visual graphics over a different scene — a scene of great tenderness, it should be noted — Vasyanovych seems to be suggesting that the act of violence that opens the film has colored everything that has come after. Serhiy and Katya are alive, but they haven’t really escaped; they’ve become the ghosts, while the past will live on, whether we want it to or not. Daniel Gorman

Seberg

Seberg is just the latest film to signal its interest in issues of racial injustice, and progressive commentary, only to counterproductively build itself around the travails of the privileged instead — specifically the rich, white, beautiful movie star Jean Seberg (Kristen Stewart). Conceiving the film around such an iconic, complex personality does certainly ensure bankability. But if we take things less cynically, there is at least a story hinted at here about the American government’s all-consuming obsession with maintaining the social status quo —even to the point of targeting society’s most visible members — due to status as sympathizer or ally. Even still, conventionality is the guiding force in a film whose moral core is a principled FBI officer, a cipher onto which audiences can project their own self-congratulatory decency. Several aggrieved black characters are pushed to the periphery in favor of Seberg’s more histrionic and palatably white-people storyline. There’s also the token villain, predictably arch, on which to direct all ire, and a laundry list of government officials who exist to embody the inherent corruption of agenda-driven intelligence agencies. Stewart, for her part, is an actress of distinctive presence, but one who can feel alarmingly incongruous if miscast. Here she’s both: her unsettled nature works in the film’s second half, as paranoia seeps in and instability shines out, but the composed, charismatic Seberg of the film’s initial stretch never fits. Ultimately, the problem here isn’t execution — director Benedict Andrews functionally, if unexceptionally, navigates through a suspense-building narrative that’s beholden to its particular structure — but rather the failing of Seberg is one of conception. In dismissing the tragedy of these characters in ways other than how they relate to Seberg, a movement’s systemic oppression is implicitly diminished and made byproduct of conspiratorial melodrama. Luke Gorham

Sorry We Missed You

For over fifty years now, Ken Loach has specialized in socially conscious dramas about working class British folk, and in our current economically fraught times, Loach’s films have particularly acute relevance. Still, at 83 years old, the power of Loach’s visualizations of these issues remains undimmed, and in recent years he’s delivered some of his finest work. That includes his latest film, Sorry We Missed You, a blistering indictment of the gig economy, where being an “independent contractor” is sold to people as a way to be your own boss but in fact proves to be an illusion, and actually traps many into high-pressure, inadequately compensated positions, with none of the protections of regularly employed work. The film goes about its indictments through the close observation of a single family being undone by these nefarious practices. Ricky Turner (Kris Hitchen), a laborer who’s proud to have never been on the dole, seeks to get his family out of debt and move them out of rental housing and into their own home. To this end, Ricky signs up to be a van driver for a package delivery company that uses independent contractors instead of regular employees. Ricky sells the family car to purchase a van for the deliveries, and thereafter embarks on long, stress-filled days getting packages to customers, accompanied by a GPS scanner that constantly tracks his location. It’s appropriately called a “gun,” since it’s a weaponized form of surveillance, determining both earnings and sanctions for not meeting delivery goals. Ricky’s harried work life is crosscut with that of his wife Abby (Debbie Honeywood), who, similar to Ricky, is contracted as an in-home caretaker to a revolving set of clients. She cares for them as if they were her own family, and while she has good relations and camaraderie with her clients, she feels increasingly stretched thin and frazzled. Ricky and Abby’s long working hours leave them precious little time to look after their two kids, who are developing their own problems. The beautifully written screenplay by regular Loach collaborator Paul Laverty gives us a visceral sense of the fragility of the family’s economic and emotional situation, where even the smallest crisis threatens to completely upend their well-being. The quietly shattering conclusion shows us what the gig economy has wrought for those trapped within it: the all-encompassing pressure of work and an unending Sisyphean struggle for survival. Christopher Bourne

Chicuarotes

Gael Garcia Bernal’s Chicuarotes tries to defy expectations for a film in which the actor-director himself plays a performer, committing itself to an exploration of the particular Mexican reality of unsettled youths, a realm where the laws of the street reigns. But Bernal so superficially roots his film in the specificity of this subculture that it falls into the trappings of the overly familiar youth-crime genre, even as the richness and distinctiveness of the language benefit from this treatment. The details, then: Two young Mexican street clowns, Cagalera and Moloteco, wish to escape the oppression of poverty and familial obligation, and they decide to do it by robbing at gunpoint the same people they tried to make laugh just minutes before. A brush with a failed robbery crystallizes for them the idea that true freedom will require something far bigger, and to that end they decide to kidnap a kid, the son of a local butcher. But no amount of local color or specific linguistic tics prevents the script from indulging in mostly conventional and clichéd narrative beats, specifically grating here as it applies to the consequences of two inexperienced young adults’ spontaneous decision to kidnap for profit. The violence present in the film might be rough for some, but it isn’t as raw and necessarily gritty as is needed to bear its thematic aspirations. For a film that so clearly prides itself on its access to and representation of the lives of the often invisible people who live in the slums of Mexico City, it prescribes to a frustratingly bland and familiar formula. A failed, stock attempt at social shock that doesn’t deliver any insight, Chicuarotes is a shallow study which seems committed only to continue down a cruel path that revels in the oblivion of its main characters. Jaime Grijalba Gomez

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open is a less garish film than its prolix title would suggest: instead, co-directors Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn have actually delivered a determined study in interruption, understated but never relaxed. The film traces a single day’s intersection in the lives of two First Nations women, Áila (also Tailfeathers), a young professional who’s disinterested in motherhood and riddled with anxiety, and Rosie (newcomer Violet Nelson), an even younger woman, of lesser economic means, who’s pregnant and deeply entangled in an abusive relationship. When Áila finds Rosie shoeless and crying, standing in the rain while her boyfriend threateningly hollers and approaches from across the street, she whisks Rosie away to the haven of her middle-class apartment. From here, The Body… delicately explores the psychology of these two women, both individually and as colliding atoms, their disparate understandings of womanhood resulting in a marathon conversation, often suspended by lulls of tension and doubt, its rhythms echoing the approximate strain or security of any given moment. The strength of the interplay between these two women is made even more impressive through the film’s formal approach: after brief introductory scenes for both characters, The Body… proceeds in the manner of a simulated, unbroken tracking shot (with impressively executed hidden cuts), the camera patient and investigative, digressing with one character here and another there, but always emotionally close. Of the two actresses, it’s Nelson’s presence which is most crucial to this film’s success: her non-professional acting allows for many moving transitions between expressions of bravado and woundedness — and her best moment comes when Áila is briefly absent from the screen entirely. With the camera trained on her face, moments after placing Joni Mitchell’s Blue on the victrola and queuing up “Little Green,” Nelson manages to wordlessly convey a history of pain – not specifically just that of women, or of First Nations peoples, or of the working class victims of wealth culture, but implicitly all of those, and untold other shades of hurt. The Body… suggests that life rarely offers easy answers — and, so, appropriately, the film offers few of its own. And while that does not make for the most complex message, nor the boldest film, it still succeeds as an elegant study in the symbiotic sensations of pain and hope. Luke Gorham

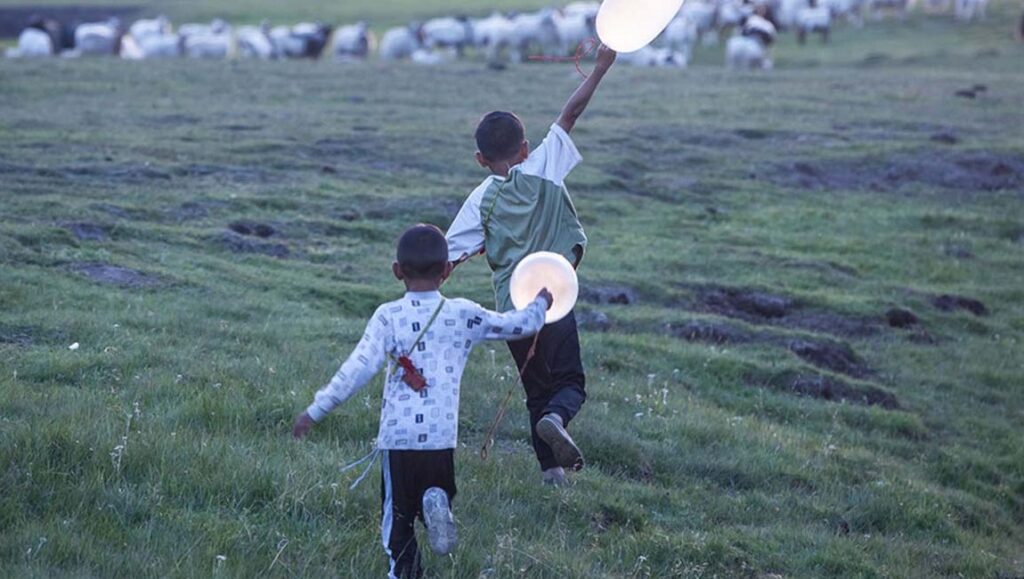

Balloon

Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s artistic intention, in both his films and short stories, has been to realistically depict the daily lives of Tibetans, without the exoticizing lens employed by others who’ve made films about them — especially those made by non-Tibetans. Balloon continues this mission, with a potent yet subtle streak of surrealism and mysticism. The film is set in the early 1980s, shortly after China imposed its one-child policy (which was slightly relaxed for ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans), including stiff fines for violators of the policy. This is the historical backdrop through which we view the lives of a rural Tibetan family of farmers. Dargye (Jinpa) and his wife Drolkar (Sonam Wangmo) live with Dargye’s father and their two rambunctious young sons, whose playful acts of mischief play a large role in driving this narrative. Initial scenes often play as a subtly droll sex comedy, as the kids play with “balloons” (which turn out to be actually blown-up condoms given to their parents by the local clinic for family planning). Dargye has a very pronounced sex drive — he’s jokingly compared to the rams he herds for a living — which causes potential financial danger for the family, as he must be careful not to get his wife pregnant again, lest he incur a fine. His boys, who continually find hidden condoms, cause all sorts of trouble for the family, who live in a very conservative and easily scandalized rural Tibetan community. (Much humor is mined from the fact that the farm animals have far more sexual freedom than the humans who raise them.) A more serious subplot concerning Drolkar’s sister (Yangshik Tso), now a Buddhist nun, serves as counterpoint. She runs into her old lover (Kunde), whose perceived mistreatment drove her to the monastery, and he gives her a novel that he wrote, which was inspired by their relationship, hoping to clear up, in his words, a “misunderstanding” about what happened between them. Tseden relates this beautifully told tale through intimate, expressive camerawork, vivid depictions of the dreams and visions of its characters, and vibrant performances by actors who exhibit the authenticity of non-professionals — even though they mostly aren’t. The Tibetan Buddhist belief in reincarnation figures largely in this story, and Tseden cleverly connects this with China’s state-imposed family planning to deliver an unstated, but unmistakable, indictment of the ways religious beliefs and authoritarian governments collude to deny women control of their own bodies and destinies. Christopher Bourne