Malcolm and Marie is an affecting meditation on the private life of relationships and the closed-door conflicts that arise in the absence of an audience.

When film and television production came to a halt last March due to the rapid spread of COVID-19, the entertainment industry panicked. With multi-million dollar productions on the line — many just beginning their theatrical rollouts — executives re-conceptualized models of distribution in an attempt to recoup losses. Whether that meant 20-dollar rental fees for Video-on-Demand or simply, inevitably, pushing back theatrical release dates for a full calendar year, such tactics showed that studio execs were willing to test these new waters and, in the process, demonstrated an openness to breaking from industry norms. But despite efforts to hold onto the market, major Hollywood studio offerings in 2020 amounted to a good deal of critical and commercial misfires: among the designated releases were projects that had been shelved for years and lost causes with no real hopes of turning a profit. For all that, there were still plenty of new films, (TV) shows, and mini-series finding release, but most were afforded little-to-no publicity. Netflix provides perhaps the best example: the streaming service allocated a large portion of its marketing budget to promote a coveted lineup of “prestige pictures,” films through which to inundate Academy voters, and left themselves spread too thin to promote other projects. New films from David Fincher, Spike Lee, Ron Howard, Aaron Sorkin, and Charlie Kaufman all brought Netflix attention — though, all of them, during a period with little competition.

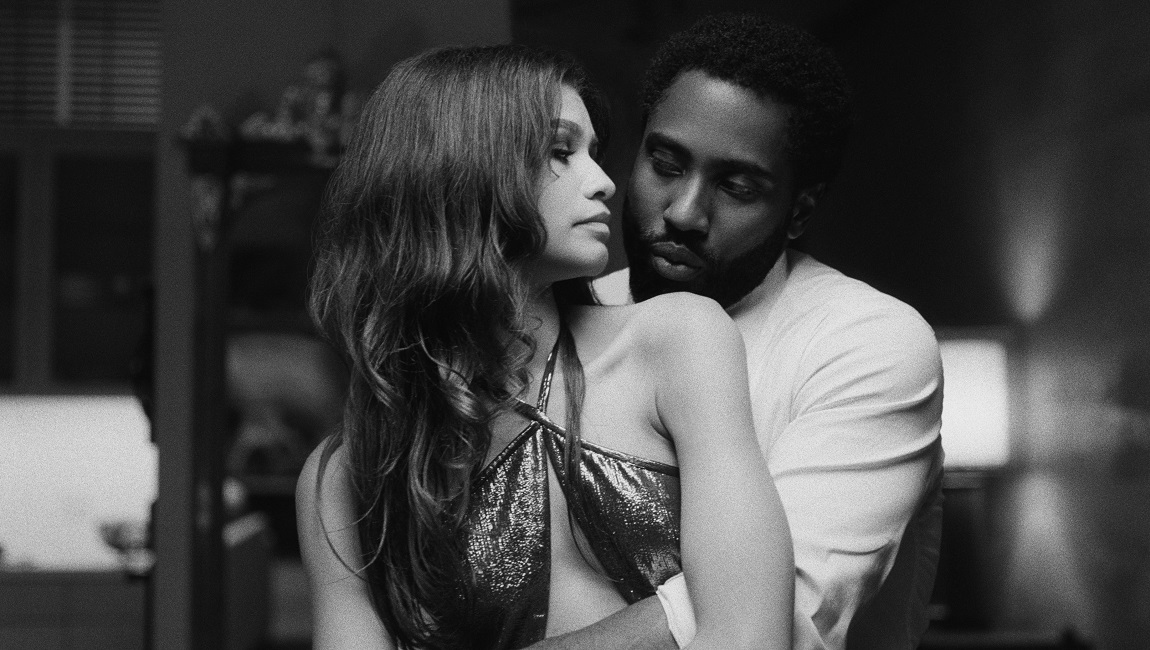

Cue Sam Levinson’s Malcolm and Marie, emerging in lieu of the much-anticipated second season of Euphoria, which had been scheduled to begin shooting in mid-March of last year — just days before national lockdowns started. Shortly after Euphoria’s production halted, the series’ lead actress, Zendaya, reached out to Executive Producer Levinson to see if he would be interested in writing and directing a movie during quarantine. Within less than a week, Levinson came up with the idea for Malcolm and Marie, which follows a filmmaker (John David Washington) and his girlfriend (Zendaya) through one emotionally fraught night; the minimalist production consisted of just two dozen crew members, and funding was provided by the film’s two stars, along with Levinson, his wife, and a few other long-time associates. That budget amounted to a relatively paltry 2.5 million, but without ties to other backers, the project was afforded a creative freedom that it might not have otherwise been granted. Ultimately, Netflix bought it up for 30 million, but only after a contentious bidding war with other competitors.

Malcolm and Marie opens with Washington and Zendaya’s title characters returning from the premiere of his new film. An egotistical director, Washington’s Malcolm rambles on about the rapturous response he’s received, all the while revealing trace insecurity beneath his self-aggrandizing monologue. Marie (Zendaya), meanwhile, steps out onto the veranda to smoke a cigarette and attempt to drown out Malcolm’s vainglorious eccentricity with the sounds outside. Back in the house, Malcolm is framed through windowpanes, a spatial barrier that cinematographer Marcell Rév uses to emblematize the inharmonious state of Malcolm’s relationship with Marie, underscoring the couple’s simmering resentment by evoking a kind of emotional dissonance. This alienation allows for a respite from the couple’s dialogues, while also asserting their individual perspectives. Close-ups of Malcolm and Marie bring us inside both of their headspaces, and the characters’ inner-monologues take root in the viewer’s consciousness. Malcolm’s self-absorption seems to prevent him from recognizing the disjunction of his relationship with Marie; his disregard for the lack of value Marie feels in their relationship acts as the dramatic foil to the dependence and loyalty she finds she still feels toward him. Marie, who’s younger than Malcolm, recognizes that she’s become the inspiration behind his art — her lived experiences inform Malcolm’s artistic success, even as he lacks his own such experiences. Across the film, then, this dispute over the conjunction of artistic and romantic collaboration leads to continuous debates that build and develop the couples’ polarization.

Malcolm and Marie was filmed at Feldman Architecture’s Caterpillar House, outside Carmel, California — a low-lying building topped with an angled, overhanging roof, floor-to-ceiling glass walls, and contemporary ranch-style architecture — and that made for a perfect location given the COVID restrictions. Despite this confined setting, the film mercifully avoids feeling like a stage-play, thanks to the camera’s active spatial engagement; Rév takes time to capture and highlight the film’s images of architecture — which work to reinforce its intimate, emotional scaffolding — while also seamlessly maneuvering between rooms to keep up with the narrative’s action. Notably, Levinson doesn’t use the pandemic as a diegetic backdrop here, as many films made during lockdown have; instead, he captures the nature of romantic spectacle during a specific moment of broad emotional alienation. In the absence of any more overt proclamation, Malcolm and Marie, then, becomes an affecting meditation on the private life of relationships, and, more specifically, the conflicts that arise in those relationships behind closed doors, when people find themselves isolated from society.

You can catch Sam Levinson’s Malcolm and Marie in theaters this weekend or stream it on Netflix beginning February 5.