Red Rooms

In 2002, Olivier Assayas’ Demonlover premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival to a storm of controversy, eclipsed — for better or worse — only by Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible that year. The controversy bespoke radicality, and that radicality remains till this day: from its premise (two corporations vying for control over an anime studio producing 3D hentai) and themes (alienation, hyperreality, desensitization toward violence) to its nightmarishly clinical design, replete with enervating spectacles of corporate espionage and totality (even the film’s title neologizes the sacred and the profane), Demonlover marked a pivotal transition into cyberspace, cementing its fledgling world as amorphous, unknown, and incomplete. Assayas’ thriller was more than seductive — dangerous even — because of the uncharted and unchartable territories it sought to navigate; the rules of the thriller’s game had fundamentally altered in favor of actions, as opposed to actors. No longer could one recourse to the limits of epistemology as the world, having been confronted with an ontological crisis of faith in the aftermath of 9/11, stood on shaky ground; knowledge itself was found wanting and, in the words of Donald Rumsfeld, “there are unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

What we don’t know, then, forms the basis for much of our contemporary obsessions both profound and mundane. Philosophical skepticism has by-and-large filled the contemporary imagination at least since the Holocaust, but its practical realizations have nary seen such influence prior to the Internet. With breadth, depth, and anonymity permitted in the cyberspace, its users have taken their desires and tendencies to their logical conclusion, surpassing them where possible in manifestations of the imagination. Of especially grotesque concern is the capacity for anonymity itself to turn libertarian instinct into panoptic paranoia — we don’t know who each of us are, but we also don’t know who’s watching us — as demonstrated by its inscription into discourses of civil liberties, cryptocurrency, and, tellingly, horror. On the Internet, fear is democratized by the unknown and our impulses, as a result, plumb the depths in search for more: conspiracies, gore channels, pedophilia forums, as well as the stuff of many urban legends — red rooms.

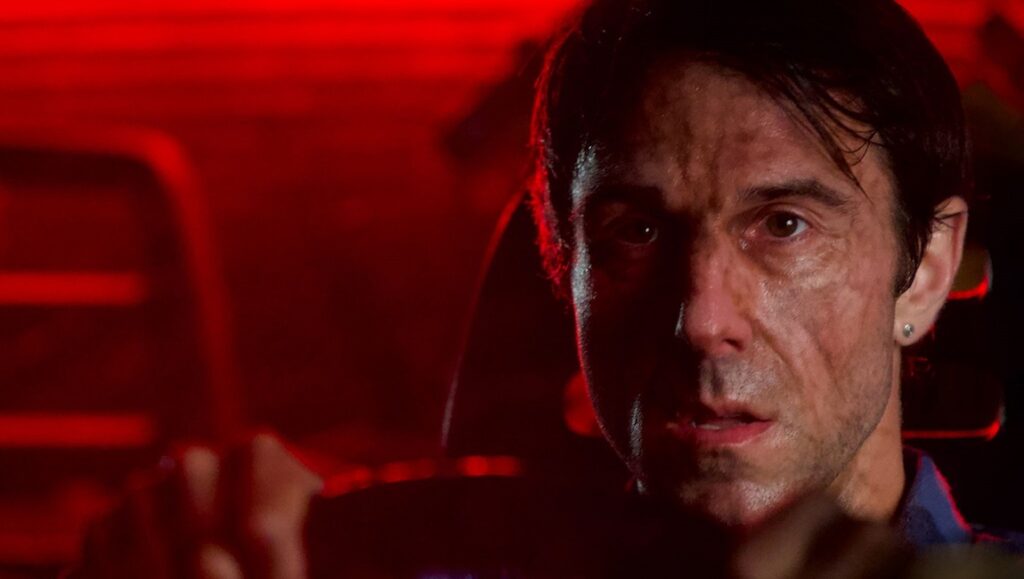

In Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms, this urban legend is assumed to be true. Hosted on Tor, a browser intended for anonymous browsing, the red room is a space that crystallizes human depravity and renders it expressible: viewers typically bid for the right to dictate the fates of human captives in these rooms, who are then slaughtered live on camera. In theory, it offers a strange comfort, consigning evil to a designated locale yet situating it close enough for queasy effect. In practice, supply and demand are equally accessible; where the hard-headed tend to camp within the latter, the paranoid are drawn to the former. Red Rooms takes as its starting premise the exhumation of several tapes from this alleged space as evidence for a crime perpetrated by one Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos) against three teenage girls. Yet the film, strictly speaking, isn’t about the crime, and neither is it really interested in Chevalier’s motivations for rape and murder. Instead, Plante shifts attention away from victim and aggressor, and onto the spectator, a lean and athletic young woman named Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy).

Kelly-Anne’s interest in Chevalier’s case exceeds the ordinary citizen’s. While its high-profile and grisly nature generates significant buzz and televised publicity, the courtroom proceedings take place behind closed doors, open only to a handful of members of the public (she among them). Over the span of months, both prosecution and defense attempt, respectively, to indict and exonerate Chevalier, while Kelly-Anne follows their attempts closely, forgoing her luxury apartment to sleep on the streets by the courthouse for guaranteed access each morning. Joining her is Clémentine (Laurie Babin), another young woman more disheveled in appearance and, in addition, convinced of Chevalier’s innocence, maintaining that the authorities have executed a witch hunt on the basis of physiognomy and sexist profiling to frame him. The mysterious and otherwise taciturn Kelly-Anne soon warms up to Clémentine, whether out of pure curiosity or loneliness, or from affection toward the latter’s naïveté.

The triumph of Red Rooms lies in this fleeting and tentative connection between its characters. Clémentine, clearly infatuated with Chevalier, resists the media’s sensationalism by importing her own (quite literally, having hitchhiked all the way to Montreal), whereas Kelly-Anne observes it dispassionately from a high-rise bubble of personal and financial success (by day, she models for a fetishist website; at night, she decimates competitors in online poker). Both embody the two primary sides of Internet-mediated obsession, as Clémentine seeks to reify the accused’s mind while Kelly-Anne directs hers down the rabbit hole, stalking the victims’ families as if to satiate her thirst for knowing. “You take your time, you’re patient, and you bleed them dry,” Kelly-Anne counsels her wonderstruck acquaintance on the art of poker. Their brief friendship, if it can be called one, invokes no Grand Guignol of romance or bloodlust, but settles for a rapport that teeters gradually into disillusionment.

Similarly, the film forgoes its titular suggestions of instant psychological gratification. It does not revel in the gratuity of the murders, and barely reveals the offending footage. Instead, the blood douses our protagonists’ faces through reflection, a crimson red emanating from the screen and enveloping the air in a dim, irresistible aura — the kind paradoxically referenced by Walter Benjamin precisely as that essence, or unique cultural context, of art which resists mechanical reproduction. In this light, their respective obsessive pursuits can be surmised as a perpetually deferred endeavor to access this haloed essence; to permeate, understand, or simply come face to face with a vision of society abandoned and superegos effaced. This endeavor is paralleled, in lighter terms, by the hubbub of legal drama, which Red Rooms smartly relegates to the periphery, save for a captivating sequence early on expounding on the matters of the case. Though its participants spar with evidence, the jury’s battle seems fundamentally doomed to the court of opinion.

At its heart, Plante’s follow-up to 2020’s eerily counterfactual Nadia, Butterfly (which was about its eponymous Olympic swimmer’s existential crisis after retirement) documents a deeply uncertain milieu where both physical and psychological terrains prove fundamentally unknowable. This milieu — in which “hurtcore,” or extreme child sex abuse material emphasizing bodily harm, proliferates on the Dark Web — lies at a discomfiting moral nexus easily blurred by accusations of sadism “inflict[ed]” on one hand and morbid curiosity on the other. We’re not sure where Kelly-Anne stands exactly: infinitely well-versed in hacking and cybersecurity, she maintains a quietly ruthless façade both in the courtroom and behind the screen, even as her excitement lets slip as the inevitable takes place and is uncovered. And therein lies the genius and aggression of Red Rooms as it reconfigures the landscape presciently surveyed by Demonlover into an uncanny and mature ecosystem of ubiquitous virtualization. Assayas, too, had a red room (the “Hellfire Club”), installed for sadomasochistic gratification. But Red Rooms is plural and indefinite, a cyber thriller teeming with the equal promise and peril of forbidden fruit. “It’s not your world. You shouldn’t see them.” Who will listen? — MORRIS YANG

Blackout

Larry Fessenden has co-starred in nine films between his last directorial effort, 2019’s Frankenstein riff Depraved, and his latest feature, Blackout. An elder statesman of modern low-budget horror, Fessenden keeps very busy, having produced or otherwise shepherded films by the likes of Jim Mickle, Ti West, Mickey Keating, Adam Wingard, and even Kelly Reichardt (people tend to forget that he starred in and produced her debut feature, 1994’s River of Grass). Dave Kehr once suggested that Fessenden was like “if Cassavetes had been working for Universal in the early ‘30s.” Indeed, the influence of those classic Universal monster movies coexists in fascinating tension with Fessenden’s own regional tendencies, scares and gore commingling with languid pacing and naturalistic, unaffected acting. In some ways, Blackout feels like a continuation of his 2001 film Wendigo — featuring another mythological creature — as well as 2006’s The Last Winter, in which environmental catastrophe (climate change) leads the ghosts of extinct creatures to rise up against humans. In other words, Fessenden has a lot on his mind, and while his films never devolve into simplistic metaphor-horror, he is nonetheless unafraid of loading his films up with meaning.

Curiously, Blackout reveals itself in form and ambience to have more in common with Reichardt’s First Cow or Showing Up than the next A24 effort. Here, a struggling artist named Charley (Alex Hurt) finds himself compelled to return to the small town he had previously abandoned in an effort to spare his loved ones from his lycanthropy. No spoilers here; Fessenden doesn’t play coy with whether or not Charley is actually a werewolf. He is, he knows it, and as the film begins, he is fleeing a roadside motel after waking up covered in his latest victim’s blood. Charley is determined to put things right before his next transformation, and this involves salvaging some kind of forgiveness from his estranged wife Sharon (Addison Timlin), while exposing his father-in-law’s illegal maneuvering to develop a new mountain resort. This man, local bigwig Hammond (Marshall Bell), was partners with Charley’s now-deceased father, and Charley must reckon with his own complicated feelings about his dad while battling his affliction. Meanwhile, Hammond is trying to pin a series of grisly, unsolved murders (all Charley’s handiwork) on a local Mexican man, Miguel (Rigo Garay). It’s unclear if Hammond is simply racist or, as Miguel suggests, has targeted him for daring to organize the immigrant labor that has been tapped to build the resort. It’s a complicated web, with Fessenden treating this small town as a kind of microcosm for America as a whole. Racism rules the day, of course, while unfettered capitalism paves over everything in its path. In a sense, Charley’s status as an outsider — a literal monster — makes him the perfect candidate to tackle these endemic hypocrisies. He has no place in this society one way or the other, and so feels compelled to burn it down before he takes his own life.

Even at a relatively brief 107 minutes, Fessenden’s insistence on following multiple characters through various narrative strands makes for an occasionally shaggy structure. The story frequently stops in its tracks to allow a couple of local cops to talk shop while investigating Charley’s murder spree, while lots of secondary characters (played by the likes of Kevin Corrigan, James Le Gros, Joe Swanberg, and Barbara Crampton) get their small moments to sketch in colorful locals (less successful are a couple of dimwitted yokels who are determined to catch Miguel and seem beamed in from a much dumber movie). But Fessenden is a fine filmmaker, and the loose vibes of the film seem wholly intentional — the hand-made, rough-around-the-edges quality is surely a feature, not a bug. But this is also an unabashed genre film, and the movie snaps into place whenever Charley transforms and goes on the hunt. To that end, Blackout doesn’t skimp on the horror goods; there are plenty of maulings and eviscerations on display. But it all hangs on Hurt’s performance, who brings a real physicality to the role. The makeup effects are cheap but highly effective, and, most importantly, allow Hurt’s facial features and movements to remain crystal clear. There’s no CGI overkill, just skillful makeup applications and Hurt’s own gestures to sell the change from man to beast (the first time we see him change, stuck behind the wheel of a speeding car, is an absolute masterclass in editing). Fessenden is also smart enough to allow Charley to be kind of an asshole, refusing to romanticize his bohemian-artist lifestyle or sugarcoat his copious drinking. Charley is filled with guilt, and fancies himself a kind of white savior, but Blackout takes care to suggest that he’s part of the problem, not the solution. — DANIEL GORMAN

The Abandoned

Tseng Ying-Ting’s crime drama The Abandoned announces itself with New Year’s Eve fireworks, a pretty little ditty in the form of Yazoo’s “Only You,” and a cop, Wu Jie (Janine Chang), sitting in her car with a loaded gun, ready to end her life. Her plans, however, are interrupted by a young girl banging on her window, crying for help. Initially startled, Wu gets out of her car to see a flock of teenagers running away in terror. She decides to investigate, and comes across the body of a Thai woman that has washed ashore.

Gripped by something like determination (or perhaps obsession), Wu forgets about her desire for annihilation and gets on the case. In true cop movie fashion, she’s stuck with a rookie partner, the curiously named Wilson (Chloe Xiang), and is forced to put her loner disposition aside as more migrant women turn up dead, the specific mutilations — their left ring fingers are cut off and their hearts removed — hinting at the work of a serial killer. The film also introduces us to Lin You-sheng (Ethan Juan), who brokers deals for employers looking for cheap migrant labor to exploit. When a body turns up at a work site employing undocumented immigrants, Lin decides to bury the body — something he ends up doing repeatedly as bodies begin to pile up — and it’s not entirely clear whether he does this to protect his racket, the immigrants, or himself by obscuring his connection to the crimes.

It’s apparent that Tseng’s ambitions for The Abandoned exceeded the restraints of a run-of-the-mill police procedural. The film is as much about Taiwan’s reliance on exploitative labor practices as it is about the murder mystery at the heart of its plot. Likewise, Wu’s tormented psyche is explored through a series of flashbacks which detail how her once-happy life has left her lonely and suicidal. The film bears the trappings of a contemporary noir, but, when contrasted with a film like Diao Yinan’s Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014), Tseng can’t match that film’s oppressive, wintry atmosphere or the depth of the director’s social commentary. Black Coal utilized a genre framework to better articulate its views on contemporary (Chinese) society — something which even the acclaimed social realist Jia Zhangke pivoted to with 2013’s A Touch of Sin and 2018’s Ash Is Purest White — but The Abandoned merely leans into both genre tropes and the melodramatic tendencies that plague much of today’s “socially conscious” filmmaking.

By setting the story in the clandestine world of the illegal labor market, there is a certain element of tragedy and despair baked into the text, further emphasized by the color palette — sickly blues, deep blacks, drab grays — as well as the protagonist’s suicidal ideation. Death is everywhere: dead bodies, dead lovers, and the constant grim reminders of loss, most notably a nasty bloodstain on the ceiling of Wu’s car. And yet, The Abandoned feels bloodless, its drama conventional. Once Wu’s husband appears in a flashback, viewers with any familiarity with screenwriting tropes will likely be able to tell where the film is heading in that regard. The central dynamic between the disillusioned Wu and the eager, wide-eyed Wilson fares much the same; it will likely surprise no one that they manage to work through their initial awkwardness to try and solve the case as a team, and even begin genuinely caring for each other, if you can believe it.

The Abandoned isn’t a terrible work, but it is stunningly unremarkable. Its humanistic outlook earns some points, but as an indictment of capitalist exploitation or the marginalization of immigrants, it’s wholly unconvincing. Tseng’s instincts — both dramatic and political, although the former fares slightly better — are nowhere near as sharp as the cineastes he seems to be looking to for inspiration (aside from Diao, there are also shades of David Fincher, Na Hong-jin, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa), turning its murkier genre flourishes into hollow affectations and its stabs at dramatic heft into television-film emotionality. Tseng is a technician in need of a vision, and until one comes along, audiences are better served by his contemporaries. — FRED BARRETT

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose

One or two festivals ago, who can remember which — this time of year they all blend together — this critic wrote about Nomad, Patrick Tam’s 1982 Hong Kong New Wave classic about languorous young adults idling away their time in young love and angular fashions before suddenly finding themselves, in the end, the targets of a politically-charged, ultra-violent thriller. This was the standard approach of the New Wave: mixing the aesthetics and ideological concerns of modernist international cinema with the genre structures of the local popular cinema. As the directors of the movement emerged, one-by-one they were assimilated into that popular cinema, changing it as much as they were, in turn, changed by it.

Half a decade after Nomad, Tam was working for producer John Sham, who had just finished a highly successful (commercially and critically) run in charge of the D&B studio. That pair’s 1989 film, My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, capitalized on the Heroic Bloodshed trend that was then dominating the Hong Kong market in the wake of John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986). But, true to form, Tam gave it a modernist twist, both in its visual style and its approach to story. Rather than a straightforward tale of blood and honor among men of violence — as in the films of Woo, Ringo Lam, and their imitators — Tam’s film is a true romance, a tragedy about people who are constantly finding themselves in traps where the only way out is to sacrifice their body for the person they love, which in turn would only lead to more violence and more heart-breaking dilemmas. Call it Romantic Bloodshed, and loop in the films that followed it: Benny Chan’s A Moment of Romance (1990), Johnnie To and Patrick Yau’s The Odd One Dies (1997), Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), and many more.

In My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, Kenny Bee plays Rick, a happy-go-lucky guy hanging around a beachside bar run by Lap (Joey Wong) and her father, Cheung, played by Kwan Hoi-san. Cheung is a retired gangster, and one day he’s obligated to help smuggle a kid across the border from the Mainland. He gets Inspector Tang (Ng Man-tat), a corrupt cop, to help, but Tang turns on him, and the result is that the kid dies, Rick needs to escape, and Cheung gets captured. Lap sells herself to Shen, another gangster (played with elegant menace by Michael Chan), to free her dad while sending the unaware Rick off to the Philippines. Six years later, the dad is a drunk, Lap’s a kept woman looked after by another man named Cheung (Tony Leung), who is sweet but callow, and Rick returns as a killer hired by Shen’s right-hand man, the toupéed and psychotic Lai Liu (Gordon Liu). One thing leads to another, as every man, in turn, tries to win Lap, either through love and sacrifice (Rick and Cheung) or violence and rape (Shen and Lai Liu). It doesn’t go well for any of them.

From its first moments, My Heart Is That Eternal Rose announces its modernity, taking the sleek swimsuits and rectangular spaces and framing of Nomad and giving them a neon sheen (it was shot by David Chung and Christopher Doyle, the key New Wave cinematographers of the ‘80s and ‘90s, respectively), which, along with the beach setting and Danny Chung’s synth score, evokes Miami Vice better than any Hong Kong movie ever has. Lap’s bar is an idyllic oasis, a place where everyone can hang out, listen to the surf, and gamble light-heartedly on bar games. Later in the movie, after the tragedies of the prologue, the bar has been sold off, turned upscale — with fancy tablecloths and uniformed staff. It’s now completely lifeless and empty, hollowed out by capital. Just as father Cheung’s generation of gangster is lost in the modern world, where honor takes a backseat to personal lust and greed — as it would for Kwan as well in Hard-Boiled, where he plays the old boss wiped away by Anthony Wong’s ruthless new boss. Rick, Lap, and Cheung are stuck in this new world, each desperately hoping to find a way out, a way to leave Hong Kong behind. The final half-hour of the film, where all the heroes, in turn, try to rescue each other by convincing them to leave the other one(s) behind, plays like a screwball escalation of Casablanca’s finale, piling one sacrifice on top of another, hoping each will be the thing that keeps the others going; hoping that, in the end, it will all amount to something more than a hill of beans. — SEAN GILMAN

The Sacrifice Game

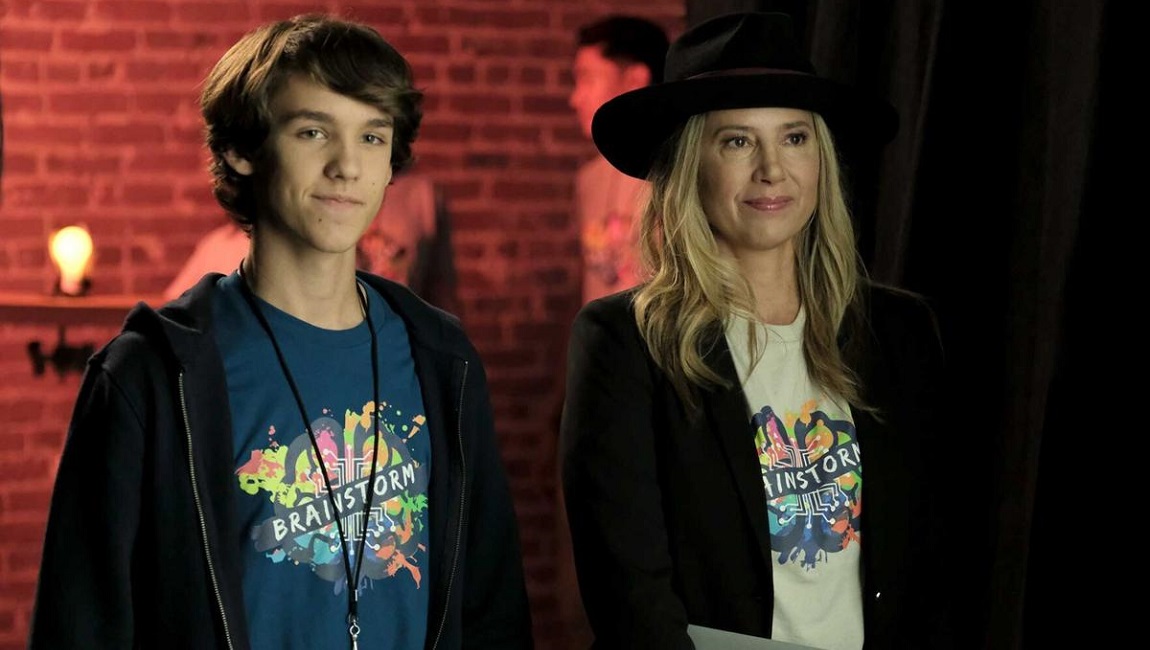

The words “A Shudder Original” don’t exactly convey a distinct meaning — not yet. While Shudder has released dozens of films, the platform is rather indiscriminate as a programmer, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It simply means that you don’t know what you’re going to get. Jenn Wexler’s The Sacrifice Game falls into this kind of machinic genre assemblage, yet it manages to stand out by shaping into something achingly cute and, at times, unexpected. Set in a girls’ Catholic school in the 1970s, the film is clearly inspired by the Manson murders. A group of killers breaks into the school over Christmas break in order to release a demon, and only Samantha (Madison Baines), Clara (newcomer Georgia Acken), and teacher Rose (Chloë Levine) are left in the school for the holidays. They alone must face off against this group, led by Jude (Mena Massoud, the former live-action Aladdin clearly playing against type and proving quite funny and occasionally menacing in his latest role). If nothing else, The Sacrifice Game is an achievement in casting, as everyone seems very clear on the film they are making — so often a problem with these sorts of movies — and what their position within the ensemble entails. Filmed in the Oka Abbey outside Montreal, there’s an intense, eerie atmosphere to the abandoned environment, naturally accentuated by the production design and set decoration, but also originating from the location’s aura — the filmmakers claim several unexplained hauntings took place during production.

This mixture of Black Christmas, The Strangers, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, and Helter Skelter isn’t afraid to tout its homages proudly, and Wexler and her team have the wit and artistry necessary to overcome these easy comparisons or accusations of mere derivation. The Sacrifice Game upends expectations in the third act, cleverly exploiting the audience’s awareness of horror tropes to push for a narrative more in line with what the characters, particularly Samantha and Clara, seem to demand. One may assume them both to be socially awkward misfits unable to fit in with the rest of the girls, but the pair reveal much more depth and eccentricity as the film progresses; Baines and Acken are certainly up to this task — Acken in particular, who gets an “And Introducing” credit and thrives in what turns out to be an incredibly tricky role to pull off.

As with any horror-comedy, a number of the jokes don’t land as intended, going too broad when the script should be more trusting of its crowd, particularly since it does exactly that when it comes to genre motifs. Wexler also struggles at times to balance her movie’s divergent tones, which may be inevitable when a screenplay ambitiously attempts to bring together so many styles, influences, and aesthetics in the hope that it coheres into something all its own. The Sacrifice Game almost gets there, even despite coming up short of such lofty goals, and succeeds enough on its own pleasurable merits. It may not reinvent the horror-comedy wheel, but The Sacrifice Game packs plenty of punch, especially near its denouement, and is a worthy addition to any streaming library. — JAKE PITRE

Aporia

Jared Moshé’s Aporia is a rare thing indeed: a high-concept, hard sci-fi head-scratcher that still feels human-scaled thanks to sensitive performances and focus on familial dynamics over mere hardware. The film boasts a compelling setup: Sophie (Judy Greer, magnetic in a rare starring role) is a recently widowed mother suffocating under mountains of stress. Her deceased husband Mal (Edi Gathegi) was the emotional fulcrum that maintained the family’s stability — since his passing, their teenage daughter Riley (Faithe Herman) has started acting out at school and refuses to socialize with friends. Sophie’s day job is extremely demanding, and the drunk driver that killed Mal is walking around free on bail while a trial date keeps getting pushed back.

The film opens with Riley being suspended from school and Sophie having to call a neighbor, Jabir (Payman Maadi), to pick her up. Jabir and Mal were friends and also scientists whose chosen careers were cut short, although Jabir tries to help out when he can. Witnessing Sophie’s dire circumstances firsthand, he decides to reveal a monumental secret — before Mal’s death, the two scientists had created a kind of time machine. It can’t send a person anywhere, but it can send an energy burst into the recent past and kill one person. Jabir’s reasoning is very simple: if they kill the drunk driver that hit Mal before the accident ever occurs, Mal won’t die and Sophie’s life will return to normal. Sophie is, of course, taken aback by the suggestion that she should murder anyone, but the idea nags at her. She eventually capitulates, thanks to grief and anger, and gives Jabir her blessing to use the machine. It works, and Mal returns as if nothing ever happened. It’s a big bold hook on which to hang a movie, flush with wide-ranging moral and ethical implications, which writer-director Moshé takes pains to explore. Naturally, there are unforeseen complications to this initial decision, and now that a sort of Pandora’s box has been opened, Sophie, Mal, and Jabir must decide how, or if, to use the machine.

There are a few obvious antecedents here: Richard Matheson’s short story Button, Button, Richard Kelly’s filmed adaptation The Box, and Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder all spring immediately to mind. Like any good time travel (or time travel-adjacent) movie, Aporia carefully explains its ground rules, mostly so that audiences can anticipate what will eventually go wrong. In Moshé’s conception of this peculiar time paradox, anyone in the room with the machine when it is used will remember everything that happened in the interim, while things outside of the room will inevitably change. In other words, Jabir and Sophie are “constants,” observers and keepers of various alternate realities that only they remember. This leads to some confusion, since the resurrected Mal has no idea that he was ever gone, or why Sophie is so emotional when she lays eyes on him. There’s also a bit of gallows humor, as the three characters must navigate changes to whatever reality they emerge into. This means Riley also has no idea about the other timeline where her father was dead for six months; she is still the science-loving youngster who does math and looks through telescopes with dear old dad.

Things begin to get complicated when Sophie decides to look in on the widow of the drunk driver that she (for all practical purposes) assassinated. Sophie assumes that he was abusive, but is startled to realize that the man barely ever drank, and that his wife dearly misses him. In another wrinkle, the woman has a daughter afflicted with a degenerative disease and little means to afford the medical care necessary to treat her. Sophie is wracked with guilt, while Jabir reminds her that thanks to him, she has Mal back. For his part, Jabir dreams of stopping school shootings and terrorist attacks, while Sophie and Mal are reluctant to use the machine at all. The trio decide that if they are in fact going to use the machine again, they have to think through every possible ripple effect that a change to the past might cause in their present.

To describe more of the plot would be unfair to viewers; Aporia isn’t a film based on big twists, but there are some surprises in store for our intrepid timeline explorers. The narrative proceeds with a careful attention to detail and a kind of inexorable internal logic, one decision leading to another and then another as consequences pile up. Moshé doesn’t dip his toes into notions of “fate,” but instead relies on a more materialist notion of concrete cause and effect. It all builds to a thrillingly opaque ending, seemingly engineered to make audiences leave the theater with different interpretations as to what it all means. It’s a bold gambit that has torpedoed many films before, but Aporia thankfully earns it. — DANIEL GORMAN