Justin Bieber

Justin Beiber wants to sell you a narrative: that the once-dumb adolescent from Ontario has grown up, found God (ok, he’s always had that), gotten married, and become a changed man for the better. This is something of a foregone conclusion to the arc he started with 2015’s Purpose, his Bildungsroman that indicated a shift away from his early 2010s teenybopper roots and into a mature professional phase. It was a thinly veiled rebranding ploy after a series of absurd episodes (including abandoning his pet monkey in Germany) and public breakups (two of the biggest singles from the cycle were in response to his former belle, Selena Gomez), but skated by on its natural charms and a grand sense of sonic scale. Then, following five years of world-charting collaborations with DJ Khaled and Luis Fonsi, he dropped Changes, a lowkey, R&B-aspiring record in the vein of 2013’s Journals, which produced fewer hits — Bieber pitiably told his fans to stream “Yummy” at all times of the day, even they were asleep, in order to chart higher — was critically reviled, and presented JB with his first case of pure parasocial disconnection.

Justice, Bieber’s sixth album, has been hastily recorded and marketed as a corrective to this minor bump, though it does feature the similar, singular thematic vision that concerned his last release: that the Biebs loves his newlywed spouse, and gosh darn it, he needs you to know about it! That might come off as a tad malignant towards the young buck, but it’s an unsurprising reaction to how across-the-board facile his songwriting is over the project’s 16 tracks: He continues to strike upon the same mawkish subject matter with such blunt-force repetition that it becomes numbing, presenting himself as a hopeless romantic who’s hopelessly out of touch with what constitutes real human emotion.

While the lyrics are unified by the laziest, most soft-boy idea of what matrimony entails, the music here is anything but; in an attempt to make sure the project is a full-proof smash across all demographics, Justice hides behind the anonymity of shameless, amorphous genre-swapping. This ranges from saccharine new-age Christain gospel — “Holy,” with original wife guy Chance the Rapper supplying one of his more nauseating verses (“Life is short with a temper like Joe Pesci”) — to ’80s-inspired neo-pop (the type that’s done well with Dua Lipa and The Weeknd, so hey, why not) on “Die For You,” where Bieber’s wispy tenor vocal range is barely able to deliver on the size of the track’s production. There’s also warmed-over EDM on the chorus of “As I Am,” wannabe dance-hall ballads with obligatory Burna Boy and Beam features, another re-try at passionless R&Bieber with “Peaches,” where both Daniel Caesar and Giveon completely outshine Bieber and his tasteless adlibs. Point being, there’s a lot going on, and virtually none of it sticks.

Which is a dirty shame, since, from a strictly technical standpoint, this is easily the finest Bieber has sounded in a minute. In particular, “Off My Face” and “Ghost” are carried by sincere vocal performances and cutesy double entendres, and are the few instances of clarity on a cluttered record built on overpleasing. Yes, they’re still safe and predictable, but Bieber has clearly signaled his intentions thus far: that he desires to be as boring and inoffensive as humanly possible, that he’s learned from his previous errors and is now thinking straight (though, the liberal appropriation of Martin Luther King Jr.’s presence throughout proves he still have a few too many yes-men in his corner granting validity to awful ideas).

The issues that plague the album are underscored on the Benny Blanco/ Finneas co-produced closer “Lonely.” The morose track aims to put into perspective the quiet pain of growing up famous, and serve as the final note of reflection on Bieber’s past mistakes, but there’s little reckoning for his past transgressions — he goes after the media, noting “they criticized the things I did as an idiot kid,” which, fair enough, but feels like a total sidestep of the issue — and it comes off as a plea for unconditional sympathy. He meets the basic requirements of the song’s objectives, but it lacks any sort of authenticity, as the best he can do to convey the crippling trauma of isolation is stretching out the ominous title with a pitiful wail (“I’m so lo-o-o-onely”) with no actual specifics mentioned. It seeks to finish this affair on a Big Gesture, and it should be a defining statement for his career and him as a person — but like nearly everything else he shoulders on Justice, Bieber seems utterly incapable of selling the moment.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: Pop Rocks

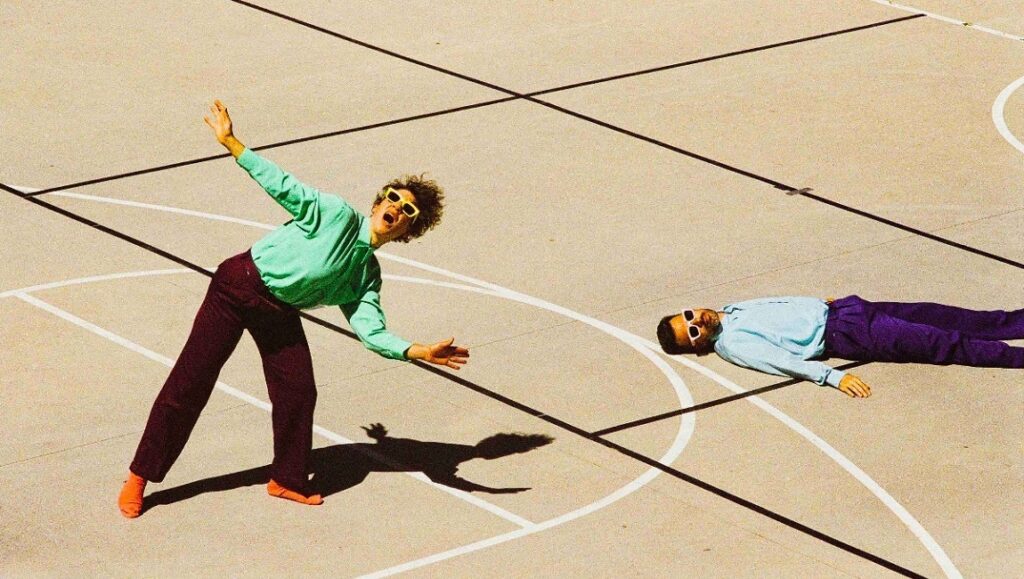

Tune-Yards

The music that Merrill Garbus and Nate Brenner have made under the name Tune-Yards (once stylized tUnE-yArDs) is born out of a collision of styles and influences gleaned from across the globe, wrangled together by Garbus’s use of looped vocals and percussion and Brenner’s complementary bass rhythms. But while Tune-Yards’ songs have always been complete and full, the seams at which their borrowed sounds are joined have always been proudly displayed — at once in homage to the loop-by-loop way in which they’re assembled, and also as an aesthetic parallel to the band’s thematic exploration of contemporary feelings of dissonance. This approach was cemented as early as the band’s debut BiRd-BrAiNs, back when Tune-Yards was a solo act and Garbus had to arrange each instrument herself, though each new album has borne out a concerted effort to rethink and reconceive in response to cultural conversations of the moment. 2011’s w h o k i l l remains the project’s peak, with Garbus articulating the nagging contradictions of our hypernormalised society long before this was a hot topic in mainstream American art. However, in hindsight, this album had its blindspots, with critics noting hit single “Gangsta”’s dubious, ironic appropriation of the title phrase, a choice that read as particularly glib on an album so liberal in its incorporations of afrobeats and jazz. These criticisms followed Tune-Yards in the years after, which presumably inspired their 2018 album I can feel you creep into my private life, a messy, electronic-skewing record that saw Garbus reckoning with white privilege and such accusations of cultural appropriation; an abrasive performance of self-indictment hard not to read as at least a little aggrandizing.

I can feel you creep into my private life was certainly Tune-Yards nadir, though it may have been a necessary reset, an exorcism of bad energies clinging on from years prior. Their fifth and latest album sketchy. implies as much, finding Garbus in much more confident form, though still very much in conversation with the woes and contradictions of our modern world. As with w h o k i l l before it, the title evokes the spirit of the time, in this case a malaise and uncertainty that permeates most of contemporary art and politics. Yet, sketchy. aims to do more than bemoan and bear witness, and it doesn’t patronize its audience with attempts to prescribe solutions to systemic and existential calamities. Instead, Garbus and Brenner have come together and produced an album inspiring in its pragmatic hopefulness, pop ballads celebrating self-affirmation and reconnecting with humanity. Which isn’t to say that the album’s tone is airy or benign; opening track “nowhere, man” starts things off with layers of clattering drums and Garbus chanting/shouting “Nowhere to run / Nowhere to hide” over them, a literal response to the 2019 Alabama abortion ban that works just fine as a summation of patriarchal terror. Elsewhere, Garbus takes on the spectre of whiteness once more on the song “homewrecker,” though this time adopting a theatrically arch perspective, talk-singing her way through the thought processes of a hypothetical gentrifier. But while songs like these and the cynically-minded “my neighbor” ground sketchy. in relatable human dourness, the album’s ultimate agenda resonates in singles “hold yourself” and “hypnotized,” the former an anthem infused with the spirit of Prince that allows Garbus to flex her impressive vocal range, belting in harmony with herself about striving to break free from humanity’s most toxic cycles. Alternatively, “hypnotized” once again layers Garbus’s vocals into transcendent harmony in praise of deep human connection and coexistence with nature. In this way, sketchy. is a grand balancing act of the sort that Tune-Yards has performed for us in the past, executed with a verve and generosity that had eluded them more recently. It’s something of a graceful return to form, unbeholden to nostalgia for what the band previously was.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: Ledger Line

Floating Points / Pharoah Sanders / London Symphony Orchestra

Promises — a ravishing collaboration between Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders, and the London Symphony Orchestra — opens with a wisp: A bright smattering of notes played on harpsichord and celeste, wafting and twisting like a leaf in the breeze. You’ll hear that same little motif repeated over and over, and probably assume it to be a prelude of some kind; a gentle ripple across still water before something more majestic storms through. You might even make it halfway through the album before you realize that the motif is never going to evolve or resolve the way you thought it might; that it’s not a harbinger of something bigger, but rather is the thing itself. This is one of many ways in which Promises teaches you how to listen: by slowing down, resetting expectations, and clearing your mind. Every virtue that the album asks of its listener — patience, tranquility, attentiveness, an openness to discovery — it embodies with all the discipline of a zen monk. It’s possible that Promises doesn’t only teach you how to hear it; it may also be teaching you how to be a better person.

It is music of such self-possessed integrity, such quiet confidence, such utter seamlessness that to divide it into parts would be folly. Though your favorite streaming service will chop it up into nine distinct movements, Promises is very much a coherent, 46-minute suite, and there is no context in which you would ever listen to it in bits and pieces. Nevertheless, the music can’t be described without noting the contributions of each of the three principals. Floating Points is the stage name of Sam Shepherd, a British composer, DJ, and electronic music visionary. He wrote that wispy little phrase that opens the album, and lets it drift in and out of spirited jazz improvisations and robust orchestral flourishes. Though it doesn’t seem quite right to call this an electronic project — even the album’s many synths feel warm and textured, as if simulating the pleasures of acoustic instruments — Shepherd obviously carries lessons learned from ambient composition and studiocraft: Promises draws its power from its length, from its repetition, from its minimalism, and most of all from its refusal to hurry. Then there’s Sanders, recording for the first time in almost 20 years, and largely leaving the violent skronk of his early days behind him. His graceful appearances on Promises feel measured but heartfelt, conveying both the earthiness and the searching qualities of jazz in a series of prayerful improvisations. Now in his early eighties, Sanders has the bearing of an elder statesman, and experience seems to have taught him how to savor the moment rather than constantly strive: The single best episode on Promises is when Sanders drops his horn and instead starts gently scatting, with all the playfulness of a toddler discovering all the fun sounds they can make with their mouth.

The London Symphony Orchestra enters in earnest about midway through the piece, adorning but never quite subsuming Shepherd’s ambient motif with opulence, dripping emotion, brazen romance. It’s a roar of ecstasy, in the midst of an album that seldom rises above a whisper, and ultimately fades into funereal organ, and a rare moment of real extravagance. But even in its more austere moments, Promises feels generous in its bestowal of beauty and serenity. That’s something else we could all stand to learn from, and Promises is a master-teacher.

Writer: Josh Hurst Section: Obscure Object

Zara Larsson

Ever since Zara Larsson broke through in 2015 with “Lush Life,” her career has been defined by a hit-or-miss anonymity. To approach songs without a clear and carefully manicured personality is, to be certain, a strategic move: it lends naturally to Larsson’s modish nature, and when the production and songwriting are strong enough, her songs can project some semblance of universal emotion. The singles that followed “Lush Life,” including “Never Forget You” and “Ain’t My Fault,” made her pop formula obvious: sing with enough bravado, and with lyrics that could signify the most basic of feelings, and the instrumentation could elevate a club banger to something more than its clunky parts.

Poster Girl doesn’t change much for Larsson despite it seeing an expansion of her sound. Lyrically, she aims not for self-mythologizing, but is instead comfortable with expressing simple ideas forcefully. At times, it’s lightning in a bottle. On her 2018 single “Ruin My Life,” she warbles and whimpers, allowing all the power to rest in a breathlessly-spoken chorus accompanied by a rumbling synth bass. Its brazen attitude is its greatest asset, making the scorching “I want you to fuck up my nights” confession feel like a private thought uncontrollably bursting at the seams. Her second-most successful single here, “Love Me Land,” is less stunning: regal strings, neon synths, and a lurching bassline provide the scaffolding for a confident and cool atmosphere, but Larsson’s stuttered coos are unnatural to a fault; they’re too obviously in service of an interesting hook.

With Poster Girl, it’s increasingly clear that Larsson’s in a peculiar position as a vocalist: she’s at her best when she’s just a vessel for catharsis rather than a pop star with discernible history and personhood. As such, when we’re reminded of her anonymity, or see failed attempts at her straying from that mold, the results can be awkward. On “Talk About Love,” the rabid pace at which the titular hook is sung makes it feel like she stepped into the studio and simply followed the melody that a topline writer provided; there’s no feeling, just melodic rhythm. It makes for a bloodless pairing with Young Thug’s feature, his delivery far smoother even in this most pop-friendly of modes.

The great conundrum of Larsson’s music is that she seems incapable of expressing any emotion convincingly. This is why she falters on songs that don’t have a stirring instrumental. “Look What You’ve Done” is one of the worst offenders, its disco-funk gloss in need of an actual diva to sell the pageantry. Instead, Larsson sounds like she’s straining to sing, failing to make the song her own. When it tumbles into a trap-inflected bridge, she sounds more market-tested than ever. “What Happens Here” fairs better, but it’s a post-Ariana trap-pop song that coasts along with little palpable consideration for its words; Larsson sings a line like “Spending time don’t mean that I’m dependent” with little conviction, and the structuring of its lyrics makes the “I don’t give no fucks” hook feel unassured. Even on Poster Girl’s most memorable cuts, like “Need Someone,” she feels uncomfortable in her own pop skin. The album’s title, then, proves apt: Larsson is here, but she remains two-dimensional.

Writer: Joshua Minsoo Kim Section: Pop Rocks

Lost Girls

“In the beginning, there is no word, and no ‘I’ / In the beginning, there is sound / In the beginning, we create with our mouths” prolific Norwegian singer Jenny Hval states in the opening moments of Menneskekollektivet, both the 12-minute song and the album, the debut full-length LP by duo Lost Girls (the other half of the group being guitarist Håvard Volden). The sparse, ambient electronic instrumentals, which are paired with poetic, carefully composed language about the body, are typical of both Hval’s sound and her explorations — her recent output includes a masterful coming-of-age album about menstruation and a strange novel that reeks of piss. “I reach for a vowel and it’s so soft / I can’t distinguish a Y from a thigh,” she later says on the track, as the production around her builds, her vocal unwaveringly committed to the spoken word. Finally, after many minutes, Hval’s singing voice at last emerges, and it sounds as beautiful as ever, luxuriating in opaque language and steady rhythms that take on an almost anthemic tone against the mesmerizing, repetitive instrumental now featuring a two-toned beat and some laser-ish, spacey synth discharges. Later, in “Carried by Invisible Bodies,” one of the most cheery-sounding tracks Hval has ever produced, she speaks about storytelling and the double fiction of creation in modernity. Much like Proust detailed a double fictitious, decade-long account of writer’s block across his In Search of Lost Time novel cycle, Hval and Volden have here written a fictitious account of the writing process, even of writing Menneskekollektivet itself.

This synthesis happens beyond the lyrics, too: most of the album’s runtime is split between the titular track and centerpiece “Love, Lovers,” which similarly builds piece-by-piece as instruments are layered with crude intentionality, the album slowly unfolding as listeners tune in. Indeed, it’s the strangest sounds and moments that propel this album forward. Starting with some unassuming drums, chimes, and bubblings, it’s a moment a bit more than five minutes in that earns the song its title; as Hval speaks about the failures of language, a riotous tambourine points toward an impending breakdown. “Words just don’t hold things like love, lovers” Hval states, delivering it like a vocal flub, a slip of the tongue before then repeating it in her head voice. Almost imperceptibly, the track builds into a cacophonous, krautrock sound, fully utilizing Volden’s talents across multiple soloing instruments. This fabulous solo work continues on to the album finale, a psychedelic track that cleverly ties the album together, capping things off with a moodily-delivered coda, completing the cycle of creation: “Where we die we become paper / Charcoals and a marker pen / Meanwhile, we are merely content / Creators of what is called real life.” Nearly a decade after their improvisatory, folk outing as Nude on Sand, Hval and Volden have returned with something entirely different, equally as unrestrained, even more curious, and with the welcome addition — literally and figuratively — of electricity.

Writer: Tanner Stechnij Section: Foreign Correspondent

Miko Marks & The Resurrectors

In the mid-2000s, Miko Marks recorded a couple of albums of straight-down-the-middle mainstream country that came and went with minimal notice and even less industry support. As Marks recently shared with Rolling Stone’s Jon Freeman, a Music Row executive told her, “We don’t think there’s a place for you,” and referred her to another label that was promoting “innovative” projects. Despite her obvious talent and the fact that her music had been fully aligned with pop-country trends of that era, Marks was told that she didn’t have a place in the country music mainstream. There’s simply no denying the institutional racism at play, and Marks, like countless other black women who have been shut out by country music’s gatekeepers, was never afforded the opportunities that her talent certainly deserved.

Thirteen years removed from her stint in Nashville, though, Marks has assembled an ace backing band and has recorded a new album, Our Country, that from its very title finds this extraordinary singer-songwriter staking a claim for what is rightfully hers. The country music industry has increasingly been taken to task during the past year over its historically and presently racist foundations, and Marks’ tremendous album — which draws evenly from folk and roots music, accessible contemporary country, and vintage soul — provides another example among many that, when it comes to country music, black women have been here and are certainly here in this moment. Our Country is steeped in of-the-moment politics, with “We Are Here” explicitly referencing the litany of injustices inflicted upon Flint, Michigan, and “Goodnight America” interpolating patriotic hymns into a meditation on the current status of the American Dream that Marks knows as well as anyone isn’t accessible to every American. “Ancestors” is a gospel rave-up that finds Marks seeking guidance from her spiritual and musical forebears, while “Pour Another Glass” and “Water to Wine” showcase a refreshing, playful approach to matters of faith. As an exploration of struggle and resilience, Our Country digs deep and offers a singular vision of the internal strength that drives a person to persevere. Beyond that thematic heft, the throughline on the album is Marks’ voice. Her technical skill is unimpeachable, but it’s her thoughtfulness as an interpretive singer that is perhaps most impressive. Her rendition of “Hard Times” is the album’s centerpiece, and the different decisions that Marks makes with her phrasing across each repetition of the chorus, paired with the easy power of her voice, create a truly riveting performance. It’s maddening to think that Music Row tried to silence a voice so extraordinary, but with Our Country, Miko Marks reintroduces herself as one of the most vital artists in country music today.

Writer: Jonathan Keefe Section: Rooted & Restless

Tokyo Jetz

What’s worse: cancel culture at large or the swath of artists aiming to capitalize on their recent popular downfalls? At this perilous moment in time, it seems as if responding to being de-platformed in any marginal way has become its own cottage industry of sorts — primarily by many male (usually white) comedians with Netflix stand-up specials astutely titled something like TRIGGERED MUCH?!? and with massive fan bases that eat this material up like slop-sucking piggies at a trough. And while there are elements of this new hyper-sensitive media landscape that could be considered as simplifying certain issues or constructing the world into a strict good-and-evil binary, these pieces of art really aren’t looking to add nuance or substance to the conversation: they seek primarily to position the act of taking accountability as a byproduct of woke scolding, implicitly arguing that those who demand abuses of power be met with appropriate gravity and rectified are being ridiculous, unfair, and unreasonable. Add to the list Tokyo Jetz, who was supposedly “canceled” last summer for joking (in the most wildly insensitive use of the word) to a male companion that she would “George Floyd your motherfucking ass,” and has retaliated nearly a year later with an album named after the subject, with cover art decorated with targeted vitriol she received in the aftermath of the incident. So she’s playing the injured party, nothing new from this brand of self-victimization thinly disguised as owning the libs, but this all bears in mind one simple question: how is one to be “canceled” if they’re altogether irrelevant in just about every way? One of the online snipes that greet the guaranteed low number of listeners sums up the entire enterprise succinctly: “Everyone saying Tokyo jetz cancelled… welll when tf you ever heard someone say ‘play that Tokyo’ tf.”

But, almost thankfully, Cancel Culture really isn’t about what its title suggests — there’s some brief lip-service paid at the start and finish, with observations made about how evil clout is — and is, instead, a nondescript rap album uninterested in introducing its star performer as someone with anything interesting to say. She’s technically proficient but utterly nondescript; each song passes by almost unnoticed, all under three minutes, and all begging to end from the moment they begin. The most obvious comparison one could make here is with the work of fellow Florida bad bitches the City Girls (the beats are snappy, the lyrics raunchy and amorous) but while JT and Yung Miami are festive and funny, Tokyo Jetz is decidedly humorless and uninspired; she even has a song titled “Flu Game” to point-blank demonstrate how stock her shtick is. Her Grand Hustle label boss T.I. — who now has a running history of signing trouble-making female MCs — appears at one point to do his Yosemite Sam-bit, which results in an apathetic chorus where he rhymes “shit” with “shit” and “business” with “business.” And if he’s not engaging with this product in any substantive way — ya know, the thing you would expect your employer to have some stake in — then another question has to be asked: why should you?

Writer: Paul Attard Section: What Would Meek Do?

Comments are closed.