Riders of Justice finds director Jensen hedging between the dank feels of his early scriptwork and the weirdo vibes of his later directorial output, to mixed effect.

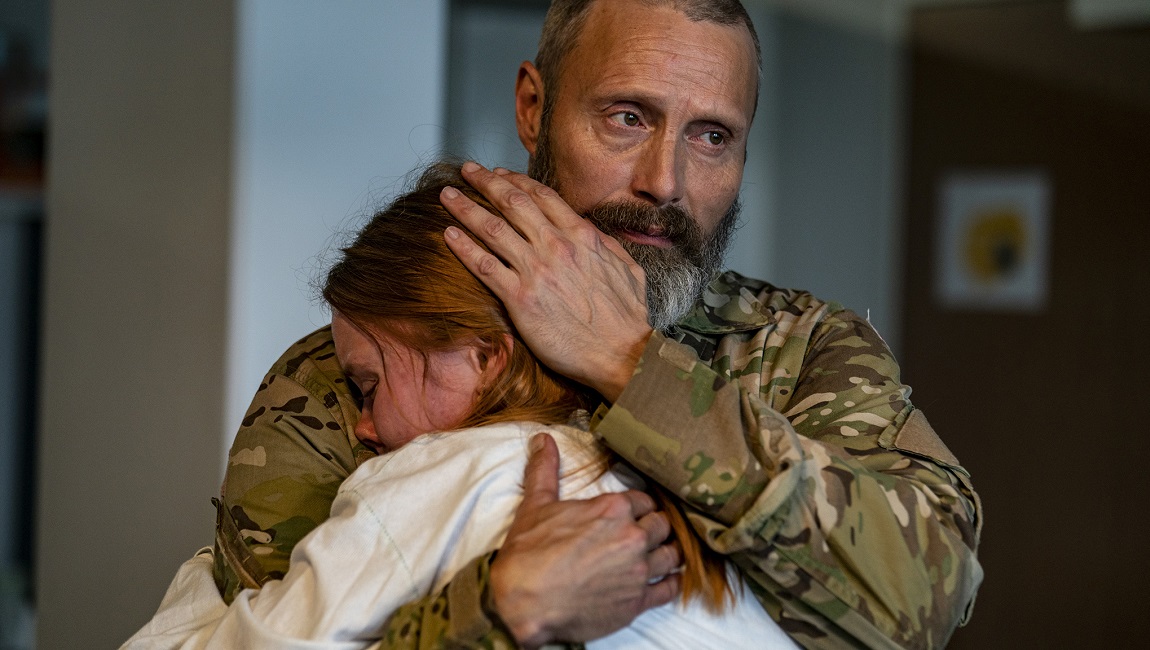

Riders of Justice bears a tone that will be familiar to those fluent in the collaborative work of director Anders Thomas Jensen and stars Mads Mikkelsen, Nikolaj Lie Kaas, and Nicolas Bro. The four have previously teamed up on The Green Butchers, Adam’s Apples, and Men & Chicken, all of which are recognizably dark comedies that also, to varying degrees, toe the line of farce. Jensen is also well-known for his screenplay contributions to Susanne Bier’s films, shaping his scripts to her more dour domestic tragedies. The latest reunion of the four Danish lads, then, finds the director blurring the lineation of these two disparate artistic worlds, to predictably mixed effect. Riders of Justice’s narrative is fairly front-loaded: Markus (Mikkelsen) is a soldier reluctantly returned home after the death of his wife in a train explosion in order to care for his daughter Mathilde (Andrea Heick Gadeberg), who survived. Also coming out scathed but sound is Otto (Kaas), a statistical analyst recently fired from his work developing an algorithm that would predict future events. After discovering that a Riders of Justice gang member who was set to testify against the brutal crime boss (Roland Møller) was also aboard and died (alongside myriad other signifiers, like a suspicious man who threw away an uneaten sandwich and drink moments before the explosion), Otto determines that the incident was no accident and, flanked by his eccentric hacker friends Lennart (Lars Brygmann) and Emmenthaler (Bro), seeks out the widower to convey his suspicions. A hardened, vengeance-minded man, Markus jumps at the opportunity to enact retribution against the eponymous criminal outfit, and soon, as such crime comedies go, all four men have become both hunter and hunted.

Given the personalities of the four men, the film’s gonzo comedy is fairly easily entrenched: Otto’s data scientist has frazzled, lite-Einstein hair, a bum arm, and a pathologically docile manner; Lennart is a distinct peculiarity, defined by his fascination with a large barn and the amount of psychological evaluation he’s endured in his years; Emmenthaler is cut from the angry nerd cloth, guided in most of his interactions by emotional fragility and a concomitant hair-trigger temper; and Markus is the straight man nucleus of the buffoonish quartet, a severe man with a severe haircut, and simmering with quiet rage. If these characters sound more like caricatures, that’s not far off, but Jensen effectively orchestrates sequences and punctuates his dialogue in a way that suggests a sub-Coens kinship — the plot convolutions and callbacks aren’t as neatly teased out and the attempt to mine pathos from absurdity falters toward the end, but the influence is evident. If the effect is ultimately limited, it’s at least not inconsiderable.

But as the film progresses toward its obvious destination, eschewing its heretofore meandering form — even if a few plot wrinkles are mixed in — much of the comedic texture is flattened in service of some unnecessary, even manipulative emotional catharsis. Seemingly inspired choices (using Mikkelsen’s familiar and imposing stoicism as foil to the surrounding, absurdist chaos) are soon diminished by lamely conventional ones (using Mikkelsen’s familiar and imposing stoicism to usher in a shallow study in trauma and some lachrymose happy-ending feels), and even the film’s potential moral knottiness is preemptively untangled when the baddies attempt to submachine gun the fellas first, thus lowering any ethical stakes. Even the big shoot-out is disappointing, the built-to sequence unduly protracted and the gunplay mostly banal. Pre-climax (and especially pre-coda), there’s a lot of outré fun to be had in Riders of Justice: Jensen borrows the bonkers grain of Men & Chicken and transposes it onto much of the interpersonal action here. The mistake, then, is that he sublimates his weirdo comedic instincts to more middlebrow aims. It’s understandable that the director wouldn’t want to indulge in mere rehash, but in kowtowing to the over-earnest emotionalism that defined much of his mid-aughts scriptwork, he largely mutes the singularity he’s been building toward as a director. The result of this odd marriage is a film that boasts frequent bursts of personality, but is ultimately rendered anonymous.

Originally published as part of IFFR 2021 — Dispatch 3.