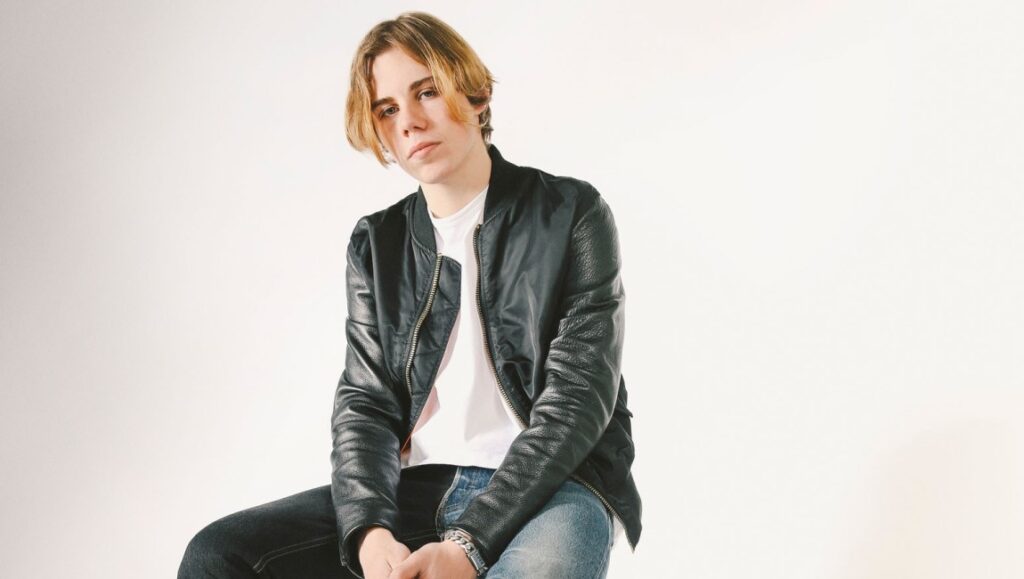

The Kid LAROI

The story of The Kid LAROI thus far, for those not in the know (which, to be fair, would be the majority of the music-listening public up until a few weeks ago): Aboriginal Australian Charlton Kenneth Jeffrey Howard, at age 14, is discovered by Juice WRLD on tour, is brought back to the States and signed to Lil Bibby, then benefits immensely from his mentor’s post-death stimulus package, goes on SNL to perform a duet with Miley Cyrus, and now, at age 17, is being managed by the modern-day Berry Gordy (Scooter Braun) and is b-ball besties with Justin Bieber. To call his recent rise in popularity meteoric would be an understatement; he’s now comfortably coasting on a career trajectory toward pop stardom, fulfilling the promise that was unfortunately never able to be fully manifested by the late Juice. But he hasn’t exactly come out of nowhere either — unless you consider Sydney nowhere, which, fair enough — and his ever-evolving F*ck Love mixtape provides something of a basic outline of his career for newcomers. There’s the first in the series, opening with the now classic “Booty Call” (skit) and following through with a seemingly endless collection of e-boy, emo-rap heartbreak anthems that found LAROI wailing away about the endless number of backstabbing bitches who’ve ruined his life — and, obviously for a pubescent, the endless amount of Hennessey he’s consuming to numb the pain. It’s deluxe edition, titled SAVAGE, found him upgrading his features list (Lil Mosey replaced by NBA YoungBoy, natch) and digging deeper into the raw timbre of his voice, sounding as if he was about to break down and collapse in the recording booth at any second.

Now we have F*ck Love 3: Over You, a deluxe edition of SAVAGE, which makes this a deluxe edition of a deluxe edition — it should also be noted that there’s a Over You+ deluxe edition that’s also been released, so a deluxe edition of a deluxe edition of a deluxe edition of a supposed standard mixtape — and on streaming services, this latest edition is stacked on top of the older ones like a series of Russian nesting dolls. Since these are all updates of one release, they’re counted as one collection on the charts; it’s a marketing move that’s equal measures genius and horrifying, foreshadowing a future where every mainstream release is this playlist-length frankensteined amalgamation of algorithm-approved metrics. Which is fitting in this circumstance, because as much as The Kid LAROI likes to scream about being blackout drunk and cutting these hoes off, he’s about as basic as this type of angsty music gets. On “Don’t Leave Me,” you have G Herbo and Lil Durk both sounding like they’re baring their souls for all to witness, begging their lovers to come back and for the Lord to forgive them — then you have LAROI coming off like he’s just been grounded from playing Fortnight for the week and name-dropping The Weeknd as someone he eats sushi with. You can find the artist in pure simp mode on “Still Chose You,” claiming he’s in love again over a boring Mustard beat, which sorta defeats the whole purpose of this ever-changing opus, but whatever. And then there’s his big breakout moment, the star-making “Stay” featuring the aforementioned Biebs — a blatant “Blinding Lights” rip-off that sounds like what you get when you ask Charlie Puth to do Max Martin’s job — which is smooth, straightforward, hits quick, is a little thrilling in the moment, but is entirely forgettable in every other respect. It reflects LAROI’s most overt move into the spotlight yet, and one can only assume the levels of celebrity he’ll ascend to once he capitalizes further on F*ck Love 4: The Henny Chronicles.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: Pop Rocks

Vince Staples

When Big Fish Theory dropped in 2017, it implied a whole new direction for Vince Staples, an artist who had arrived on the scene seemingly fully formed, outfitted with a defined perspective and style already evident on his early Shyne Coldchain tapes. His casual, direct delivery and appealing annunciations mapped on to classically-minded gangsta rap production quite nicely, making him a natural collaborator for the likes of No I.D., who produced his debut LP Summertime ‘06 in full. That album, and the EPs fixed on either side of it, positioned Staples as an artist who could navigate the rap generational divide quite naturally, though these initial projects generally paid more favor to less contemporary aesthetics. Arguably, Summertime ‘06, with its lengthy double album format, took this preference about as far as it could go, and so Big Fish Theory, backed by a stacked line up of contemporary electronic producers like Flume and late icon Sophie, offered a savvy and exciting step forward for Staples that he has yet to surpass.

But the rapper has kept busy since then, quickly following up Big Fish Theory a year and a half later with the slight, L.A. radio-themed FM! (appropriated and reworked by Tyler for Call Me If You Get Lost), while taking on an Adult Swim voice acting project (Lazor Wulf) and kicking off a Vevo show (something with Netflix coming soon). And now we have the self-titled Vince Staples, another sparse, 22-minute album in the mold of FM!, though without that one’s unifying concept and playful sensibility. Reliant entirely on production from Greenwich, Connecticut’s own Kenny Beats (largely responsible for FM! as well), Vince Staples finds the Long Beach rapper coasting and uninspired, leaning on well-worn tropes and the corporate competency Beats brings to the table. Staples remains an exceptional rapper and a cool, charismatic MC, but unchallenged by the straightforward material provided by Beats, Vince Staples mostly serves as a reminder of its artist’s technical prowess and little else. Taking a tonal turn toward the grim and downbeat, Staples uses this album’s 10 tracks to reflect once more on his fraught, violent youth, and present-day paranoias. A switch up from FM!’s sunnier vibes, Vince Staples goes somber more often than not, returning to memories previously articulated on Summertime ‘06, though now with the benefit of a few more years hindsight.

Staples remains a savvy lyricist, able to articulate large chunks of narrative with a couple quick, precise phrases, but the writing here is otherwise frustratingly uniform from song to song, looping back to the same ideas, each virtually indistinguishable from the next. In theory, Kenny Beats’ superficially eclectic production style should provide enough of a freewheeling backdrop for Staples to get away with enacting this inert drama, but the majority of his genre change-ups don’t hit (reggaeton guitar on “Take Me Home” entirely fails to register, for instance), and his stylistic dabblings never really sound better than their reference points (“The Shining” sounds like Pi’erre Bourne’s “Sunflower Seeds” but less good, “Taking Trips” like a flat take on a Migos-type composition). Vince Staples is a strange album, obviously born from earnest emotion and a desire to be candid with its audience, but it otherwise scans as a perfunctory exercise, a placeholder maybe (there’s the much teased Ramona Park Broke My Heart on the horizon, after all). This tension isn’t not interesting, and one could imagine it becoming something greater if it were approached with intent, but that’s something generally lacking from Vince Staples, a largely unmotivated album that frustratingly never sparks to life.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: What Would Meek Do?

The Wallflowers

The existence of a new Wallflowers album — arriving a full nine years after the sleek, vaguely funky Glad All Over — can’t help but raise the question: What’s left to distinguish a Wallflowers recording from one of Jakob Dylan’s solo LPs? Certainly not personnel; Dylan is the only person who’s played on every single Wallflowers album, and he and producer Butch Walker fleshed out Exit Wounds with a gang of studio ringers. Perhaps the distinction is more a matter of vibe. Though there exists no Wallflowers signature sound to speak of, the songs on Exit Wounds benefit greatly from a sinewy full-band sound, pitched somewhere between bar band and heartland rock, and a far cry from the subdued introspection of Dylan’s solo albums. Dylan obviously wanted to make some noise with this one, and he does: The album crescendos with “Who’s That Man Walking ‘Round My Garden,” three minutes of cowbell and pounded pianos, as gloriously trashy and throwaway as anything in his repertoire. And even when Exit Wounds isn’t stirring up a ruckus, it still feels robust and full-bodied; opener “Maybe Your Heart’s Not In it No More” takes its time exploring a spacious groove. It’s also one of several songs here that features prominent harmony vocals from Shelby Lynne, an invaluable and high-profile backup singer.

The album’s loose, leathery sound befits Dylan’s usual world weariness, and it highlights his gift for songs that manage to be unfussy without being bland. He occasionally gestures toward the theatrical —”Move the River” churns with a majestic, E-Street locomotion — but his sweet spot is conveying jadedness and disappointment through simple conceits (the Tom Petty-ish “The Dive Bar in My Heart”) or wry self-deprecation (the singalong “I’ll Let You Down [But I Will Not Give You Up]”). A lot of songs are about lovers who have either parted ways, or at the very least reached the end of their rope, and typically the narrator knows it’s his fault; “the best thing about me is that I used to be yours,” Dylan deadpans, the closest he comes to really cracking a joke. Maybe it’s not a conventional party album, but it is a resounding testament to Dylan’s ability to write about uncertainty and loss from a place of empathy rather than self-pity; and, to the enduring pleasures of his roots-rock craft. With any luck, he’ll pull together some guys to make yet another Wallflowers record before another full decade passes.

Writer: Josh Hurst Section: Pop Rocks

Wavves

So great was the thirst for music festival-friendly indie rock in the latter half of the 2000s that for a moment, garage rock revivalism caught on, mainstays of the scene like Black Lips and Thee Oh Sees became more broadly visible, newer artists like Ty Segall and Jay Reatard helping to glamorize what was seen as unsophisticated. It was a phenomenon few benefited from more than Nathan Williams and his band Wavves, which began life as a lo-fi, DIY-type project backed by drummer Ryan Ulsh, before transforming into a trio, absorbing Jay Reatard’s bassist and drummer (not long before his untimely passing) and losing Ulsh following a much-publicized freak-out at Primavera Sound Festival. Though that moment quickly became integral to the band’s mythos, the more traditionally arranged three person version of Wavves, with Stephen Pope on bass, has persisted far longer and with considerably less incident, releasing a string of studio albums and a couple EPs over the course of the last decade, the best of which remains 2010’s millennial-iconic King of the Beach (plus follow up EP Life Sux). Not as thoroughly committed to the garage rock thing as the aforementioned artists, Wavves remained fresher than most of their contemporaries longer by staying open to a variety of sounds, most obviously incorporating surf and pop punk (it wouldn’t be unfair to give them some credit for the latter’s recent normalization), but also hip hop-influenced looping and sampling (Williams’ Sweet Valley side project opened for Killer Mike and GZA concurrent to Wavves post-King of the Beach success). 2013’s Afraid of Heights was still a pretty good album, bolstered by a more expensive production budget, but the posturing bratty nihilism that had long been the underpinning of their artistic perspective was already beginning to wear thin, its credibility tied pretty directly to youthfulness.

One might then ask: “What does Wavves have to say in the year 2021?” The answer, unfortunately, is more of the same, though less convincingly. This latest album, Hideaway, their seventh, arrives four years after their last effort, the loop-centric You’re Welcome, and brings the band back to more traditional vox-guitar-bass-drum compositions. Williams, Pope and new drummer Ross Traver are totally comfortable making music this way, unchallenged even, but the former artist’s hooky pop songwriting prowess is still apparent at least, and several songs on Hideaway are quite melodically satisfying, catchy at the very least. But the album is mostly directionless, taking us on an aimless journey from thrasher punk material (openers “Thru Hell” and “Hideaway”) into janglier pop material with psych undertones (closers “Planting a Garden” and “Caviar”). Produced by TV on the Radio’s Dave Sitek and featuring faux-Dalian artwork, one might expect Hideaway to be a more experimental record than it works out to be, but in fact, this might be Wavves’ least adventurous work to date aesthetically. Meanwhile, Williams is as petulant as ever, his lyrics mostly revelling in the disdain he has for the women he romantically involves himself with and his general indifference toward commitment. Granted, no one’s asking for a wholesome version of this band, but the one that ultimately shows up for Hideaway is simply too unpleasant and tedious to want to spend much time with.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux Section: Ledger Line

AKMU

Although they’re under the K-pop umbrella, sibling duo AKMU (brother Lee Chanhyuk and sister Lee Suhyun) make music that’s different from the usual idol-pop sound you might associate with the genre. Their work, which is largely self-composed, leans toward poignant singer-songwriter impulses and live instrumentation, which has made them favorites of the Korean general public. Although it’s been almost two years since AKMU released a studio album, the break has proved to be worth it: their new project Next Episode is one of the best, most well-balanced K-pop albums of the year.

Episode is a collaboration album, with each of its seven tracks featuring a prominent Korean artist singing alongside the siblings. In order to complement these features, the production runs through a wide variety of genre signifiers — there’s disco, R&B, funk, and soft-rock all intertwined with traditional pop hooks. Perhaps the most impressive part of the album is how smoothly the tracklist progresses through these different features and genres, making every transition feel like a natural progression despite the stylistic shifts that occur from song to song. It’s an impressive feat for a project of this length: seven tracks is too long for a hyper-focused EP and too short for an exploratory full-length, so you need perfect execution and vision to make your album both cohesive (without getting stuck in a rut) and stylistically daring (without that cohesion falling apart). AKMU pulls it off.

Next Episode opens with the pre-release single “Hey Kid, Close Your Eyes,” a muted, disco-influenced song featuring Lee Sun Hee. Retro concepts have been the most popular trend in K-pop for over a year, and with every new K-pop act that jumps onto the retro bandwagon, it seems like the trend gets closer to tiring itself out. Yet, after months and months of synth-saturated comebacks, K-pop artists are still finding exciting new ways to push the sound. The rise of “sophisticated disco” has been far and away the best recent development in this area, with huge names in the Korean music scene turning in groovy but delicate retro singles that, rather than exploding outward in a burst of neon, seem meant to make quiet moments more special (see: Heize’s “Happen,” IU’s “Lilac,” Taeyon’s “Weekend”). The smooth, subtle production and featherlight melodies of “Hey Kid” make it a top-tier entry in this field, but what really sets the song apart is its solemn tone. “Hey Kid,” whose Korean title translates to “Battlefield,” is part apology, part coming-of-age lesson for a younger generation forced to inherit a world scarred by war: “Hey kid, close your eyes / Hang in there just a bit, although it’s suffocating / Because here on the battlefield / Once your ears stop ringing / There’s gonna be screaming.” The video features somber black-and-white scenes of children play-acting a battle; the synth motif that ends each chorus could almost be a siren. Don’t worry, the rest of the songs aren’t nearly as grim, but as the first single and first track on the album, “Hey Kid” showed listeners exactly what to expect from the songs that follow — thoughtful, skillful writing and production that only improve with repeat listens.

The next few tracks on Episode showcase different, equally compelling takes on the retro trend. “Nakka,” the big release-day single, features K-pop legend IU and is one part “Blinding Lights,” one part Taeyeon’s “Something New” — a bit sleek and synthy, a bit funky, and just a little bit ominous. “Bench” (with Zion.T) is built around a gloriously cheesy “Black or White”-style guitar riff and has one of the best opening lines of the year (“Sometimes I just wanna lie on a bench / Fall asleep for a day, and wake up / To find everything gone”). Track 4, “Tictoc Tictoc Tictoc” (with rapper Beenzino), can best be described as “chill AKMU beats to study and relax to” and marks the turning point of the album as it transitions from dance-y retro sounds to more relaxed singer-songwriter fare. The last three songs are all midtempo tracks with R&B and rock-leaning instrumentation, and among them, closing track and Sam Kim duet “Everest” is a highlight: Starting out backed by nothing but a quiet acoustic guitar, it gradually builds up into a swelling soft-rock song (check out the live performance, which may be even better than the recording). Smartly written and produced, perfectly balanced between vocal and instrumental focus, ambitiously varied yet cohesive: AKMU’s newest work is a highlight of the year in pop so far. Despite being an album based on collaboration, what comes through most strongly are the voices and vision of Chanhyuk and Suhyun, who pull the project’s disparate influences together into a strong statement of identity. As the duo’s first release since renewing their contracts under YG Entertainment earlier this year, Next Episode feels like a milestone in AKMU’s career — and, hopefully, a sign of more just-as-great music to come.

Writer: Kayla Beardslee Section: Foreign Correspondent

EST Gee

It’s so far been a big year for the big-foreheaded Yo Gotti and his CMG record label — also known as the Collective Music Group, who previously went by the less marketable and far-better namesake of the Cocaine Muzik Group — between the recent success of Detroit’s 42 Dugg and continued rise of Memphis’ Moneybagg Yo, who’s affiliated with CMG via a management deal. Both are huge accomplishments in their own rights and worthy of celebration for the CEO newcomer (not counting whatever Blac Youngsta is doing these days), but there’s no slowing down over at Gotti’s office. Now, it’s Louisville’s EST Gee’s time in the spotlight, who signed with the label early in 2021 after the popularity of his Ion Feel Nun mixtape, and its appropriately titled sequel, I Still Don’t Feel Nun — he was also shot five times and lived to tell the tale, in case you weren’t in the know — and has recently dropped Bigger Than Life or Death to continue this professional winning streak.

Opener “Riata Dada” sets the stage well enough: you get these blaring horns over this loud, grimey trap beat, the type Jeezy would rap over in 2004, as Gee delivers this slurred, snappy stream of consciousness rant where he’s connecting these elongated independent clauses like he’s some bookie simply rattling off statistics (he even cheekily makes note of how his “semi spit like a run-on sentence”). His boisterous confidence borders on pure arrogance, his swagger is completely unchecked, and his delivery barrels through like a runaway train; simply put, he’s a relentless dude who couldn’t give a fuck less. Which, in small doses, is thrilling and provides its own unique pleasures: “Make It Even” and “Sky Dweller” find him in a similar mode of operation, and when he teams up with Pooh Shiesty on the piano-heavy highlight “All I Know,” the two quickly get down to brass tacks and sound gleefully savage while doing so. In fact, one could say Gee is something of a veteran when it comes to getting to the point of things, as most of his songs comfortably stick to the two-to-three minute range while also ditching the usual fundamentals of musical structure (choruses, complex arrangements, bridges) in the process; he would probably claim that all of that stuff is unneeded, and for him it probably would be. But that leaves a lot of tracks that don’t have much of an end game beyond being loud and aggressive, and by the time Gee’s label mates start showing up again and again to help pad out the project’s length, one starts to become a bit numb to the experience (that might actually begin when Future, on the “Lick Back” remix, makes a rather bizarre claim that he’s “suckin’ this bitch titty like I’m tryna get some syrup out it”). It’s a bit too much of a good thing, yet never outright invalidates what’s come previously; in that sense, Bigger Than Life or Death functions best as a brief showcase for the raw potential its star artist regularly exudes. Or better yet, and perhaps a bit more accurate: as warning shots for those still not in the know.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: What Would Meek Do?

Comments are closed.