The First Wave isn’t much more than an ornamental object, pointlessly self-assured in its distasteful aesthetic manipulations.

The compartmentalization that contemporary documentary tends to engender — divorcing thematic intent from aesthetic misguidedness — is undoubtedly exacerbated in the time of the COVID-19 film. Considering everything that has transpired since March 2020, the prospect of viewing Matthew Heineman’s The First Wave is reasonably and understandably demanding, a reiteration of the unknown capabilities of a virus that is still running rampant, all telegraphed from within Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York during the first few weeks of the pandemic. It’s a never-ending avalanche of new patients, of resorting to last-measure equipment, of rushing between rooms as varying alarms go off. Heineman occasionally cuts to drone shots of a depopulated New York City: an unnerving contrast of portent-laden stillness and frenzied, exhausted activity.

The sacrifice of generally everyday contact is made resoundingly painful: not only are family members only allowed to see their hospitalized loved ones via video, the iPads and tablets themselves are sheaved in reams of plastic. The pandemic has necessitated barrier upon barrier between human contact. The patients that are subject to the most focus are what have been termed “essential workers,” and Heineman is admirably intent on outlining how the virus worked its way through different working-class communities, how it could infect an entire household within only a matter of days. It’s impossible to deduce a pattern from both the recoveries and the deaths, as numerous doctors and nurses make clear, and it’s this uncertainty that colors much of The First Wave.

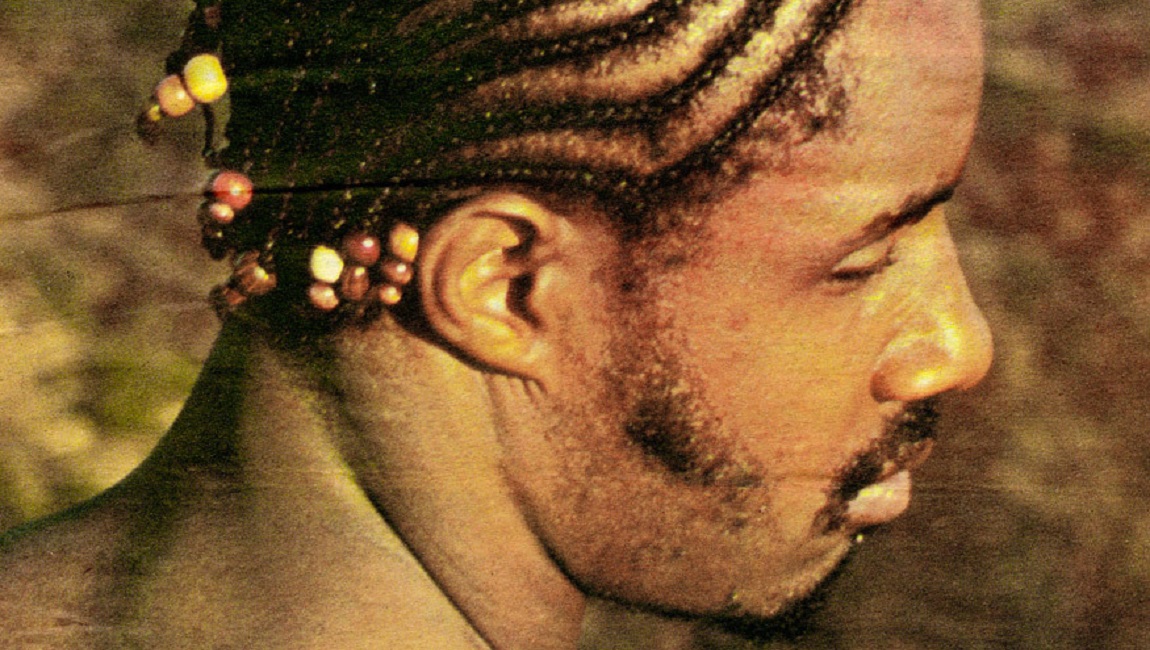

Heineman operates neither from a vantage point of hindsight, nor does he attempt to neatly cap off the pandemic at the end of his documentary (the title itself implies the continuing series of peaks and valleys we’ve witnessed). The time-capsule properties — the evening banging of pots and pans briefly makes its way in sometime around April; the protests of early summer rightfully occupy much of the last third — are the most intriguing, but much of the documentary otherwise buckles under the passage of time. One can’t chide Heineman for being attracted to his chosen handful of hopeful stories, but the subsequent aestheticization of Brussels Jabon and Ahmed Ellis’ recoveries sours the produced feeling of optimism. Uplifting music, incongruous slow motion, invasive closeups: it’s as if The First Wave doesn’t trust us to untangle the victories from the losses, though that’s what the entire world has been left to do these last two years. This unprecedented climate is crammed within a conventional framework. Even just excising some of the distastefully ominous soundtrack cues would’ve set The First Wave a few notches above its current placement. It should be said that it isn’t too soon to take the pandemic head-on in film, although it is untimely to render the resulting project as an ornamental object, one that is so pointlessly self-assured in its aesthetic manipulations.

Originally published as part of DOC NYC 2021 — Dispatch 4.