An inconspicuous FedEx parcel starts its journey on a desolate Texas dirt road, goes “snowbound,” and ends up in post-USSR Russia a few thousand miles away, placed in the capable hands of Mr. Cowboy. This simple yet global exchange of capital, as outlined, makes up roughly the first five minutes of Cast Away’s 143-minute runtime. This small, faceless interaction, condensed and streamlined, also serves as one of the many theses that run throughout Robert Zemeckis’ island-set epic: the ways in which fate and chance (in this case, the unpredictability of the natural world itself) guide and shape our lives, even down to the minute details. As systems analyst Chuck Noland (a pudgy Tom Hanks) points out, if one FedEx delivery truck is only a few minutes late, that tardiness will slow down the next delivery; then, the next will be even more behind schedule, resulting in a series of small failures. What may first appear to be a small goof ends up building into something greater, reverberating outward and affecting anyone in the wake of this blip. This is why Chuck is so concerned with time, you see: it instills order within chaos — or at least tries to, even when things are still clearly in disarray. Chuck wears a wristwatch, carries a pocket watch with a photo of his girlfriend Kelly (Helen Hunt), and asks about the time at every turn; yet, he never seems to have any for himself or his loved ones. During a Christmas meal with his extended family, Chuck remains beholden to his job and checks his pager non-stop.

This all changes for Chuck rather quickly. He takes what should be routine a job in Malaysia, where, instead, his plane crashes into the sea (with a heavily-strobed sequence that could be mistaken for a flicker film when removed from its original context) and he washes ashore onto a desert island located somewhere in the South Pacific. Now, Chuck has nothing but time. So much time, in fact, that the island itself becomes a zone of temporal destabilization, one where days begin to casually slip by into weeks, where months eventually turn into years. Bird calls and insect buzzing have been all but removed from the audio mix; instead, all we hear is the calming white noise of the crashing ocean waves. It’s here where the film enters into a far more relaxed pace and rhythm, where Zemeckis’ traditional long takes — which, during the film’s first half, are texturally crammed and almost frantically scurrying about — become less mobile and outright stationary as Chuck becomes accustomed to his new environment. Extreme long shots repeatedly display the comparative insignificance of Chuck’s plight in the grand scheme of things, with his bouts of physical rage leaving next to no impact on his immediate surroundings. When he stumbles upon a dead pilot’s body and buries it, he makes note of the uncaring blitheness of the situation: “So that’s it?” he openly asks to an uncaring world. He never receives a verbal response; maybe that in and of itself is the answer Chuck was looking for anyway.

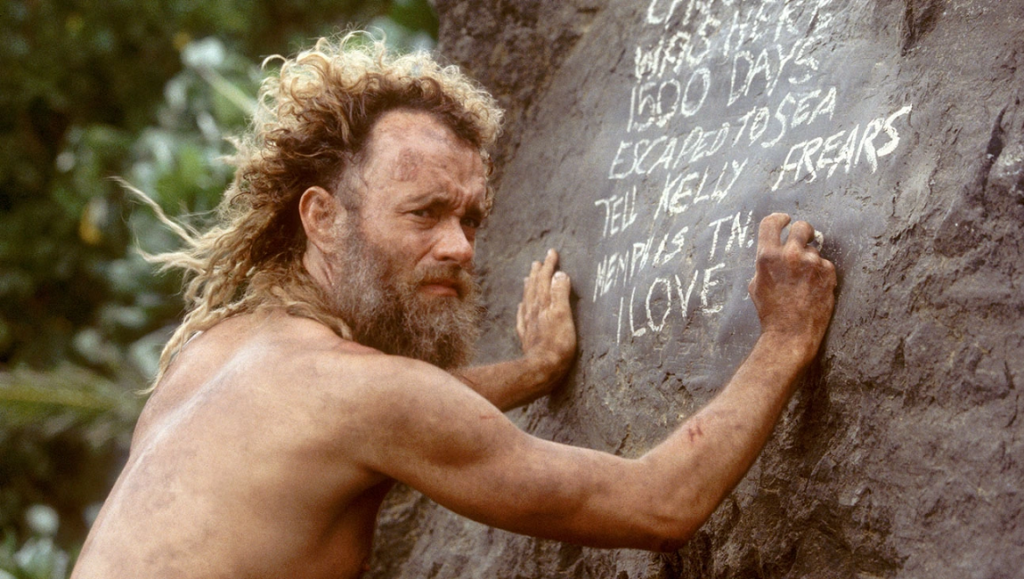

There’s an instinctual drive to Cast Away’s middle section that borders on primitive, once it’s finally removed from the too cute, almost winking quality of the homebound first 10 minutes, where cheap lines like “I’ll be right back” are crassly scattered about for easy emotional payoffs later. The first thing Chuck does when on the island is call out for help; when that doesn’t work, he writes “HELP” onto the sandy beach; when the tide erases the message, he uses a series of logs to spell out “HELP” again. The logic that follows from each action is clear and precise; this the type of narrative coherence, exploratory in its approach, is one that doesn’t need obtrusive things like dialogue or exterior motivations in order for it to make sense. But that doesn’t stop Zemeckis and screenwriter William Broyles Jr. from tacking those sorts of contrivances on anyway: while the inanimate object known as Wilson is a beloved figure by many, it’s fundamentally a cheap prop meant to get Hanks talking again after a long stretch of semi-silence. Soon, the theatrics come out; what was turning out to be Hanks’ most reserved performance proceeds to fly off the rails.

Things get even more dire once Zemeckis and co. move off the island, which constitutes the film’s final act — realistically speaking, this should serve as the opening for another film entirely. There’s just, conceptually speaking, too much that should be going on in terms of the psychological fallout related to these particular set of circumstances. In order to truly envision the horrors of being completely cut off from the world at large for four years, one has to take that step-by-step in documenting the slow rehabilitation of Chuck back into society. Well, we don’t get that, or really anything that comes close to that. If anything, it’s an achievement how little the ending of this movie actually achieves in terms of an emotionally satisfying payoff: Chuck reunites with Kelly, now married with children, but can’t go through with it. Even through all of that, Zemeckis and Broyles can’t envision Chuck as anything other than a nice guy; you’d think that, with all that time gone, he’d be more than willing to make it up any way humanly possible, that his many brushes with death would have pushed him to embrace his respect of time even more. It’s this that proves to be Cast Away’s essential problem: while the adventure it conjures proves to be an exciting bit of technical filmmaking for a stretch, there’s ultimately little here that attempts to complicate the narrative and transform it into anything legitimately melancholy or pensive.

Part of Robert Zemeckis: Movie Magician

Comments are closed.