An auteurist’s dream, the films of David Cronenberg have continued to express their creator’s psychosexual pet themes for half a century now, nearly without deviation. The ideas evolve and the perspective changes — this is why last year’s Crimes of the Future felt fresh rather than merely cumulative or self-referential — but, even when the genre shifts, it’s easy to see each new work is of a piece with those that preceded it. Sometimes reduced to a purveyor of body horror, Cronenberg is instead interested in bodies and minds, between which he draws no line. The physical, mental, sexual, psychological, and even technological are part of one whole in his work. This is what connects a dramedy about Freud to Viggo Mortensen fighting in a bathhouse with his dick out to Jeff Golfblum violently transforming into a fly. And while these predilections were apparent from the start of his career, it’s with Videodrome that they coalesce into the stunning thesis that would define his work up to the present.

On the level of craft alone, Videodrome represents a significant step forward for the director. With a bigger budget and studio backing for the first time, Cronenberg and his established collaborator Mark Irwin turned in work that looked better than anything they had made before, boasted incredible effects from the already legendary Rick Baker, and starred an actually great actor in James Woods, not to mention a great performance from Debbie Harry. But rather than a compromised big-budget studio project, Cronenberg used the money to go even further and untether his work from the conventions of genre. Where films like Rabid or The Brood fit the filmmaker’s concerns into easily legible subgenres — one a zombie film, the latter basically a giallo — the structure of Videodrome proceeds from its ideas. The result is a work that is both more upfront about its thematic concerns and more deliriously disgusting. It’s a dense, hard-to-parse discursive horror film that features a horrific sight as indelible as The Brood’s climactic reveal nearly every ten minutes.

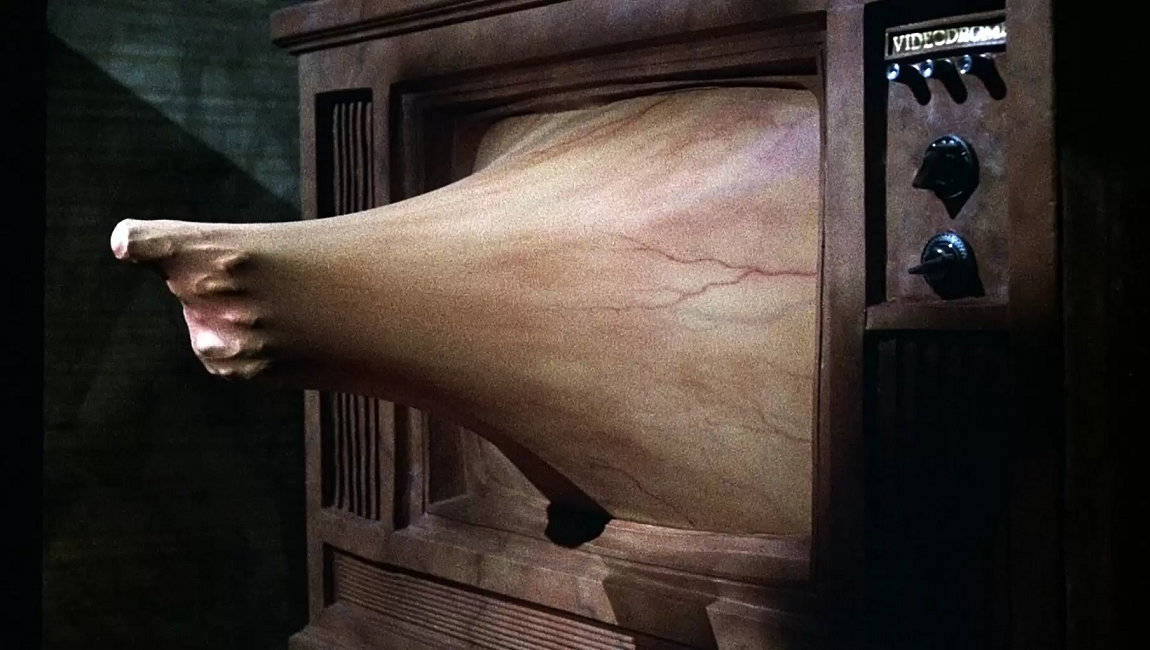

Released into an era as obsessed with images of sex and violence as it was censoring the same, Videodrome posits that all that visual stimulation changes the brain chemistry of the viewer. When soft porn-peddling TV exec Max Renn views the pirate broadcast of “Videodrome,” a program of BDSM snuff, he first tries to acquire it for his own channel before succumbing to its insidious, hallucinogenic effects. That the alleged signal is coming from Pittsburgh is perhaps a nod to George Romero’s influence on Cronenberg and everyone else; in the same way that the film’s delirious violence proceeds from Renn’s first viewing of “Videodrome,” so does all the horror of the ‘70s and ‘80s proceed from Romero. Viewing the program causes a brain tumor — or is it a new organ — to grow, leading to increasingly grotesque hallucinations that become impossible to distinguish from reality as the film goes on. Renn’s hallucinatory visions account for all the iconic body horror effects which don’t blur lines between sex, technology, and violence so much as destroy them — before any breathing VHS tape enters the vaginal flesh VCR growing on Renn’s stomach, he inserts a gun.

As much as it might be tempting to reduce this to an especially delirious parable about how TV is probably bad for the brain, there’s little in the way of a moral framework here. Instead, it’s an observation of capitulation to overstimulation. Debbie Harry’s alluring Nicki Brand is first introduced as Renn’s counterpart on a television panel — along with Brian O’Blivion, the man who never appears on television except on a television set — about the effects of sex and violence on television, where she states that “We live in overstimulated times” and that the constant state of media consumption can’t be healthy. But, far from a hypocrite, she’s the first to admit to living in a state of stimulation herself; when she goes home with Renn, she reveals herself to be much kinkier than him, into knifeplay and burning her breasts with cigarettes. She feels the allure of “Videodrome” more strongly than he does, though their attraction is entirely different. When she disappears to Pittsburgh, she does so in search of an experience, actual sexual gratification, an earnest curiosity, and appreciation of the debauchery on the screen. Max Renn is a cold, corporate sort of pervert who likes “Videodrome” because he sees the profit in it. When the film’s actual villains are revealed, the creators of “Videodrome” are people like him seeking a corporate takeover of his own television channel. When you’re distracted by sex and violence on TV, you miss the real story of the 1980s: the damage of unfettered capitalism.

Beyond what is on the screen, Videodrome is about the screens themselves. As the “media prophet” O’Blivion puts it, “the television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye,” an extension of the human body and one of many new organs in the Cronenberg oeuvre. Obviously, it’s an organ for sight, and what is seen on television functions as the mind’s reality, the same way Cronenberg does not differentiate much between hallucination and reality. But its organic function goes beyond the obvious implications of that statement. It’s also a new brain by which to achieve religious ecstasy and philosophical thought. And for O’Blivion, television has replaced his entire physical existence. Murdered by assassins in the employ of “Videodrome,” he now exists only in the form of thousands of videotapes, achieving an afterlife of being wheeled out on a TV screen. Most thrillingly, this extension of the body is a sex organ. Repeatedly, we watch Renn either seduced by a television — literally sucked into Nicki’s lips as they appear on the increasingly convex screen — or engaged in some other sex act with one, as when he whips the fleshy CRT set in his own experience on the show.

Compared to the technosexual thriller at hand, the film’s strange spiritual dimension is harder to untangle. O’Blivion and his daughter Bianca run the Cathode Ray Mission, a religious organization that gives those in need doses of television like a soup kitchen for video. Television is the new religion here, but for most of the film, there’s not much interest in exploring the dimensions of his ministry. But in the last stretch, religious allegory is pushed closer to centerstage. As programming videotapes are inserted into Max Renn, switching his allegiances repeatedly, he eventually emerges as an emissary for the O’Blivions in their fight against “Videodrome,” repeatedly saying “I am the Video Word made flesh.” Brian and Bianca O’Blivion’s ministry finds its unlikely messiah in these final minutes as Max Renn is reborn and martyred for their cause. Admittedly, it’s hard to find the allegory here especially cogent instead of simply another provocative part of a stew of signifiers that point in many directions.

Good science fiction does not strive to be predictive, but becomes prophetic by projecting a paradigm shift in the present moment that will reverberate for years to come. Videodrome’s psychedelic idea that television screens are an extension of the human body has, in reality, only evolved as the number of and uses for screens in daily life has increased astronomically. It’s at this point passé to suggest the science-fictional idea that smartphones are cyborg-like augmentations to the human body, new organs through which we perceive the world around us and now literally use to have sex, but that is what Cronenberg already posited about television in 1983. Videodrome is in everyone’s pocket, all the sex and violence in the world at your fingertips. Cronenberg resists applying too much morality because what would be the point? We might still live in overstimulated times, in a nearly numbing fugue of constant arousal, but there’s no going back. We are remade in the image of our technology. Long live the new flesh.

Part of Kicking the Canon — The Film Canon.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 5.