In the summer of 2001, Lionsgate distributed two brutal films about young adults carrying out murderous conspiracy plots against their friends. The first, Larry Clark’s Bully, premiered at the performance-focused Method Fest in mid-June, and was distributed in the U.S. theatrically the following month. In late-August, Tim Blake Nelson’s O (Othello) saw release, following a recent cycle of Shakespeare adaptations reimagined for contemporary young adult milieus (Romeo + Juliet [1996], 10 Things I Hate About You [1999], Get Over It! [2001], etc.). Although Clark’s singularly vicious vision differs significantly from Nelson’s more conventional one, these back-to-back releases exhibit fascinating thematic and tonal convergences, most specifically in terms of their shared moral complexity.

Both films’ mutual resonances gesture to a burgeoning sense of pessimism in America at the turn of the century, the cumulative consequence of environmental disaster, reactionary politics, racial tensions, and national and military violence. Consider, for example, Richard Baumhammer’s racially-motivated mass murder in 2000; the ecologically catastrophic Martin County coal slurry spill the same year; and the inauguration of far-right George W. Bush as U.S. president in January 2001. Bully and O were also released two years after the Columbine High School massacre, which spurred several major studios to delay, cancel, or significantly rework any films depicting young adult violence. O was itself originally scheduled for release in 1999, but was ultimately delayed after Columbine High’s Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold murdered twelve of their classmates and one of their teachers.

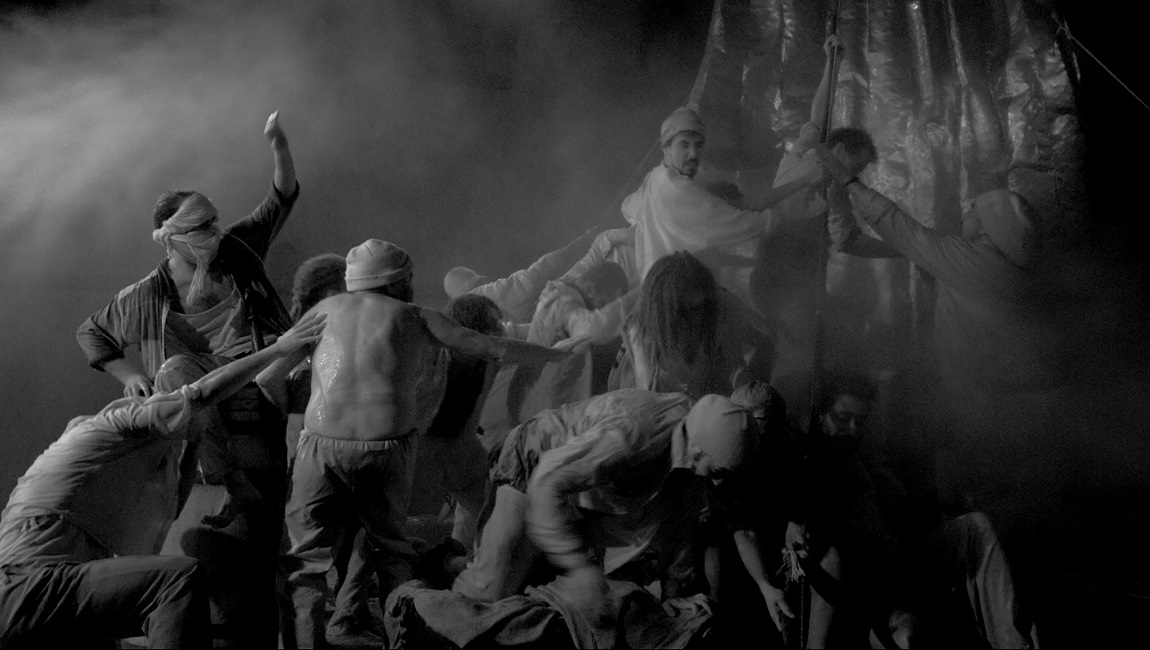

Neither O nor Bully use these bleak sociopolitical events as means to support alarmist representations of juvenile violence. Instead, both films offer serious and unpatronizing investigations of the darkest corners of contemporary young adulthood. O follows the plot of William Shakespeare’s jealousy- and obsession-focused tragedy Othello, with Josh Hartnett playing a renamed Iago (Hugo), villainous frenemy to Odin James (Mekhi Phifer). Where Shakespeare’s Iago is blatantly motivated by racism, O’s Hugo facilitates his plot to undo Odin with more obscured racist implications; he means to win his autocratic father’s (Martin Sheen) approval.

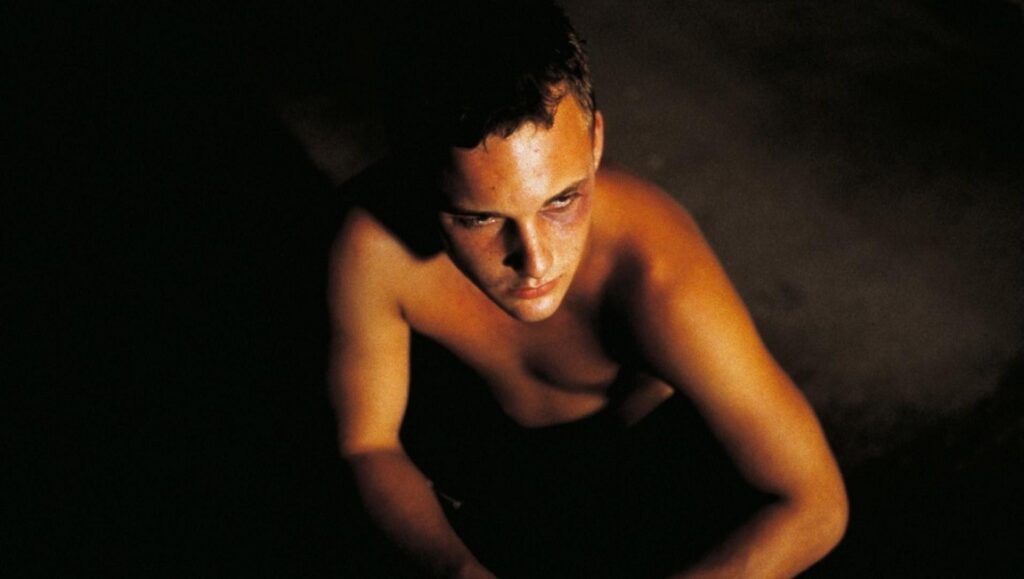

Based on Roger Pullis’ true crime book of the same name, Bully follows a group of aimless young adults conspiring to murder their own friend, serial rapist and abuser Bobby Kent (Nick Stahl). Unlike O, the target of this young adult murder plot is a substantially less “innocent” character than Odin. But in both films, the murder target grapples with his own conflicted masculinity, and with his father’s domineering and subtly sinister presence.

Both films also mine their grim stories for nuanced and complex dealings with group morality. The films’ central acts of violence are dislocated from single guilty parties, arising instead from stews of personal, familial, and social factors. O’s Hugo acts as the film’s devious narrative architect: he manipulates others to join his plot to exterminate Odin, whom he perceives as the ultimate threat to his masculinity. Bully finds its own Shakespearean plotter in the scheming orchestrator of death, Lisa (Rachel Miner), a contemporary approximation of Lady Macbeth — it is no coincidence that, after her friend group viciously butchers Bobby in a remote glade, she frantically insists that she can still smell the young man’s blood, even despite her accomplices’ assurances to the contrary.

In both films, Manichean moral systems falter. Neither Hugo nor Lisa represents a one-note cipher of evil. Instead, Bully and O grant their dark Shakespearean puppeteers a human pathos — Clark’s film emphasizes the intensification of Rachel’s insecurity and low self-esteem under her boyfriend Marty’s (Brad Renfro) abusive and dismissive behavior, and O locates Hugo’s quiet pain in the presence of Duke, his belittling, emasculating father and coach. Bully and O further emphasize their respective diffusions of guilt through the structures of ensemble drama — Bully’s drug-hazed group collectively (and haphazardly) plans and executes the murder of Bobby, while O’s Hugo depends heavily on sycophantic classmate Roger (Elden Henson) to set the stage for his nefarious scheme.

Clark and Nelson’s films parse their engagements with guilt by drawing subtly on their sociopolitical milieus — interestingly, Gus Van Sant’s 2003 minimalist high school shooting drama Elephant explores related ideas to similar effect. Bully and O are awash in contemporary cultural signifiers, soundtracked by ‘90s and ‘00s hip-hop, prickly with the recent Columbine massacre’s implications of rage-filled, adolescent male disenfranchisement. O’s wealthy, white, handsome Hugo is suffocated by the imposition of his father and school’s rigid class and gender expectations (bound up in subtle and not-so-subtle forms of racism); and Bully’s largely uneducated, hopeless youths drift hazily through an environment typified by drug dependency, existential purposelessness, and casual misogyny.

Indeed, these films are brutally confrontational in their portrayals of socialized sexism: in a red haze of jealousy, O’s Odin rapes his girlfriend Desi (Julia Stiles); Bully’s Bobby exorcises his repressed queerness by sexually humiliating and trafficking several friends, including his best buddy Marty, and by raping his on-and-off lover Ali (Bijou Phillips) while forcing her to view gay pornography. In O, Desi minimizes her own experience as a victim; in Bully, Lisa laughs aside her friend Ali’s trauma. Lisa’s moral murkiness connects to her more generalized state of tragic denial, flippantly proposing the murder of Bobby Kent and daydreaming about the possibility of sharing a child with Marty, even despite his abusive response to her pregnancy. O’s own complicated “villain,” Hugo, devotes his entire sense of self-worth to the masculine spectacle of high school basketball games, injecting HGH, and forming malicious schemes off-court to fill his psychopathic void of self-comprehension.

Certainly, these films share a fundamental interest in the moral quagmire endemic to their contemporary America. Clark affords his sweaty, lusty, Florida-set Bully the same textual immersion and brutal verisimilitude that had permeated his oeuvre up to this point — from his stunningly brazen 1971 debut photography collection, Tulsa, to his harrowing, Cassavetes-esque 1995 debut film, Kids, to his texturally vivid 1998 crime-drama Another Day in Paradise. Bully is a film centered on images, befitting an auteur whose cinematic expression is steeped in his experience as a photographer: Clak exhibits a pruriently eager obsession with his cast’s bodies and sexualities, and he places pictorial emphasis on their milieus (the film is sticky-hot with the texture of beaches, middle-class domiciles, video game arcades, and humid Florida streets). Though O does not reach Bully’s level of bold aesthetic sophistication, it does deliberately relegate most of its drama to the basketball courts and residences of its high-class prep school, stressing Odin’s visible racial marginalization within the almost ubiquitously wealthy whiteness of its student population.

These films’ visual particularities supplement their overarching visions of doomed American adolescence. To watch Bully and O is to experience the bleakest of turn-of-the-century, young adult American cinema. The pictures are exemplary in their brutal honesty, ethical opacity, and pessimism. And while their dramas are distinctly intimate, Bully and O transcend the notion of a narrow scope, gesturing to far larger cultural anxieties and crises.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 7.