In Emmanuel Carrère’s Between Two Worlds, Juliette Binoche’s character, Marianne, is introduced as a credibly depressing symptom of the global economy. In her fifties and boasting an advanced degree, she hasn’t been regularly employed in more than two decades, having helped her husband run their small business. After he left her for a neighbor, she found herself on her own, desperate for any source of income and, with a 23-year gap on her resume, the best she can hope for is work as a cleaning lady (euphemistically called a “maintenance agent” by an employment specialist here). Living out of a sad, one-bedroom apartment in northern France, initially without a car and rapidly depleting savings, she attends job fairs where she has to pretend that cleaning is her passion and try and answer questions about her biggest flaw in a way that sounds like an attribute (she smartly answer that she’s “a perfectionist”). At a moment in time when white collar and middle-management jobs feel especially vulnerable to being made redundant — Marianne’s even told cleaning jobs are the future because they’re “always needed [and] can’t be delocalized” — it’s all rather sobering and very “there but for the grace of God…”

It’s also a well-orchestrated fabrication. Marianne is, in reality, a celebrated author researching a new book about the dire financial straits of the working poor and has gone deep undercover to live as her subjects do. The crummy apartment and having to navigate bus schedules at odd hours of the day are real, but, presumably, there’s a posh flat in Paris (not to mention the advance for the book sitting in her bank account) waiting for her once she has enough material for her to shed this persona. And therein lies both the central tension of the plot as well as the film itself: can art appropriate poverty for the express purposes of humanizing the plight of those afflicted by it without either inherently exploiting it or condescending to its subjects? Does the mere fact that Marianne chooses to suffer “needlessly,” scrubbing toilets for minimum wage and trudging out in the middle of the night in order to arrive at job sites by 6:00 AM cheapen the experiences of those who can’t escape from this life? Is there something inherently cruel in nodding along to tales of hardscrabble existence only being shared under the pretense that it’s between peers or allowing someone to pay their share for a tank of gas that they can scarcely afford to maintain a subterfuge in service of bringing an important issue to light? And what of the film itself, which casts one of the most glamorous actresses in the world in Binoche and asks her to not wear makeup or wash her hair, appearing opposite mostly non-actors playing barely fictionalized versions of themselves, all to inform an audience that attends the sort of arthouse theaters with wine bars in the lobby? Is there any way to navigate all of this without feeling kind of icky?

The answer is “it’s complicated.” Like Marianne, Carrère — who returns to directing after a nearly eighteen-year hiatus following 2005’s The Mustache — puts the work in, dedicating large chunks of the film to depicting the back-breaking effort of cleaning a public bathroom or turning over a ship’s cabin in 90 seconds. The film recognizes how underappreciated the work is without being precious about it, instead attempting to portray the dignity in being good at your job, no matter what it is. Most importantly, and in keeping with her role as an observer, the film positions Binoche as a reactive figure rather than a savior or someone who needs to be humbled to learn an important lesson about themselves. Putting to lie the idea that just anyone can do this type of work if they’re willing to degrade themselves enough, the film allows the character to be believably terrible at her job without being patronizing about it, even having Marianne get fired almost instantly from her first assignment for failing to show sufficient subservience toward an impatient supervisor. But mostly the character is there to listen and learn; serving as the eyes and ears of the audience and allowing her colleagues, mostly women of a certain age, to talk about their dreams and frustrations. As Marianne happily tags along for social gatherings and family outings, ostensibly as research, she begins to develop attachments with her subjects, muddling the ethics of the assignment.

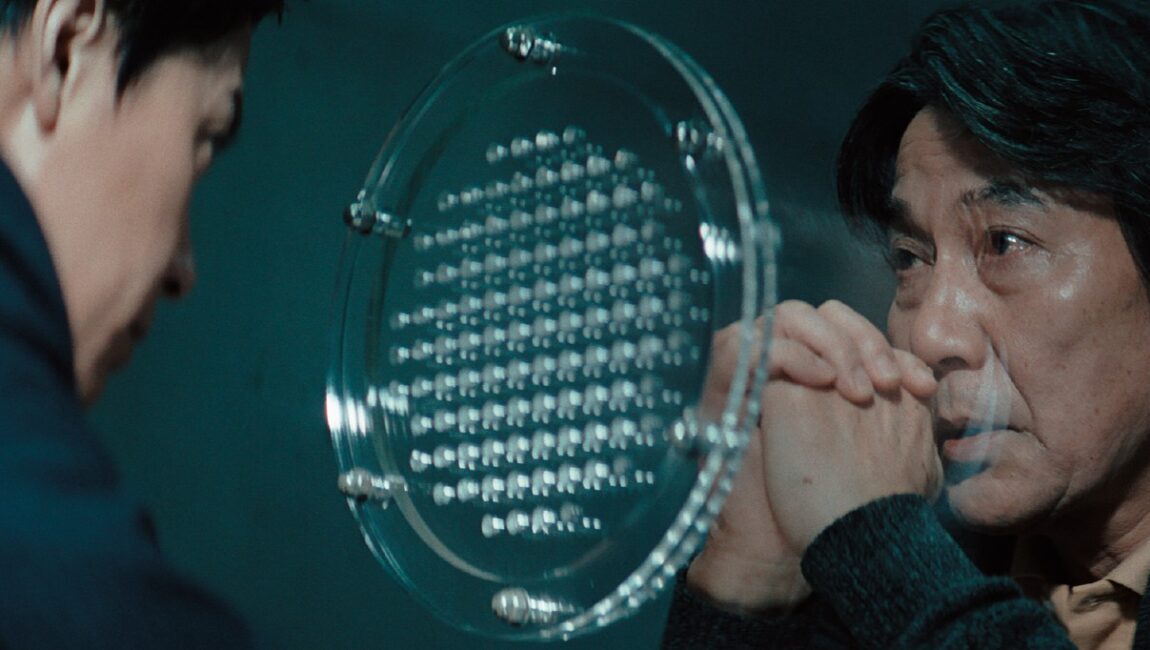

None of the women make a greater impression than Christèle, a single mother of three young boys, played by first-time actor Hélène Lambert in a revelatory performance. First introduced at the same employment office where we meet Marianne, screaming at civil servants because her welfare has been temporarily cut off and leaving her to loudly inquire how she’s supposed to feed her children, Christèle remains in the film’s orbit, sourly attending training sessions for the umpteenth time so that she can retain access to job placement and government subsidies. The character is pragmatic, resourceful, and utterly free of bullshit, and her resolve stirs Marianne, particularly her willingness to walk miles in the dead of night to report to work. The two women grow close after Marianne volunteers to drive Christèle to a job cleaning a ferry that sets sail daily from the port city of Ouistreham — which gives the film it’s actual French language title — with the younger yet more experienced Christèle viewing her new, formerly bougie, friend with wry curiosity and ultimately empathy (she’s genuinely tickled to learn Marianne used to employ a maid). And Lambert is giving an affectless, thoroughly lived-in performance here, betraying little while conveying warmth entirely through her eyes and a crooked smirk, which is the closest the actress comes to smiling.

The more Christèle takes Marianne under her wing, sharing her homelife and demonstrating generosity at the expense of her own needs — Marianne catching Christèle snooping around in her wallet is paid off in a scene that sweetly upends our expectations — the greater the emotional toll it all takes. Binoche plays these later scenes as though the truth were trying to claw its way out of her body; the actress responding to moments of camaraderie and kindness with an overpowering desire to come clean and, accepting that’s not possible, repeated attempts to swallow her feelings. When her cover story finally does give way, as it invariably must, the film is honest about the fallout, acknowledging the feelings of betrayal as much as it does appreciation of the effort. The film tempers any self-congratulatory impulses, noting for every person who feels seen by Marianne’s benevolent stunt that there’s still someone anonymously emptying trash cans and cleaning out cubicles while she’s back to having her hair styled and attending book signings. The film ends on a deflating, uncertain note, calling into question whether anyone’s life has truly been improved by celebrity activism or if it’s all merely an act of penitence to assuage a guilty conscience (without entirely shooting down whether it’s worth the attempt in the first place). Whatever your feelings on the subject, the film seems to have internalized them as well, and is attempting to grapple with them in earnest.

DIRECTOR: Emmanuel Carrère; CAST: Juliette Binoche, Hélène Lambert, Louise Pociecka; DISTRIBUTOR: Cohen Media Group; IN THEATERS: August 11; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 46 min.