In 1993, when the third edition of Japan’s biannually held Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival took place, no one could have foreseen the seismic impact that this event would have, has really continued to have, on another country’s national cinema. That story isn’t exactly obscure anymore, at least for those with some knowledge of the minutiae of modern Chinese film history: A handful of young mainland Chinese documentary filmmakers, all invited to YIDFF ’93 to screen either their first or second features, by chance attended a festival showing of Frederick Wiseman’s Zoo and found themselves enthralled with the American documentary giant’s use of what they’d soon recognize as direct cinema.

Various interviews and oral histories have been published about this encounter — notably, a recent piece for Chinese Independent Film Observer by Akiyama Tamako, a translator at Yamagata, sketches out not only the excited conversations that she overheard taking place between the young Chinese filmmakers after that fateful Zoo screening, but also details how the most well-known member of this group, Bumming in Beijing director Wu Wenguang, managed to bring back from Yamagata bootlegged VHS tapes of many of Wiseman’s other films with him to China, where he held screenings for peers who were not able to travel abroad. Through my own research on this subject, I discovered that these VHS tapes were not only screened at Wu’s home, but also copied, at a CCTV studio nonetheless, and distributed, serving to further the reach of their influence — and going some ways toward explaining why so much of the so-called New Documentary Movement in China bears a striking resemblance to Wiseman’s cinema.

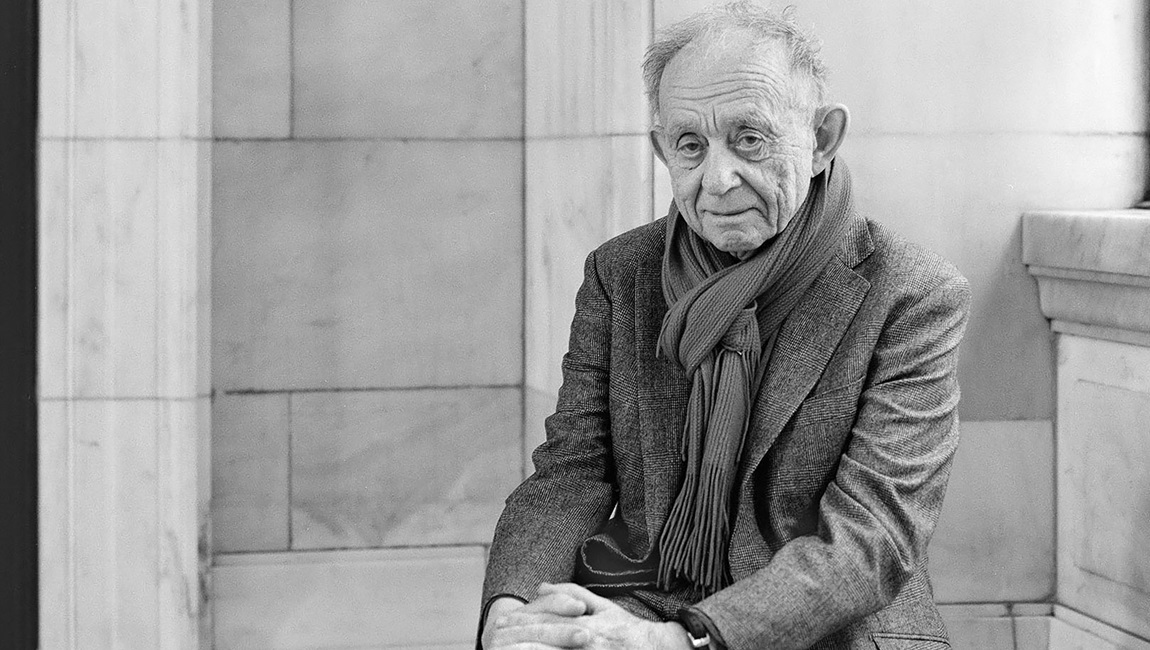

There’s one person, though, who hasn’t commented all that extensively on this subject, and that’s Wiseman himself. And so, when afforded the immense privilege to speak with the 93-year-old filmmaker, I couldn’t resist but take a sizeable detour from the subject at hand — the release of his 44th documentary, on the family-run operation of three high-end restaurants in the pastoral French countryside — to explore his awareness of, and his apprehension toward, the use of his films in China, from the impact that he had on that first generation of filmmakers in the early 1990s to the evidence of his influence on Wang Bing, one of the most prominent documentarians on the film festival circuit today, Chinese or otherwise.

This interview was edited for clarity and concision.

Sam C. Mac:

Thanks so much for doing this with me. You’re in Paris now, right?

Frederick Wiseman:

Yeah.

SCM:

I’m really excited to do this interview. I hope you’ll indulge me a little bit of a sidetrack conversation. My research is focused specifically on Chinese film and Chinese independent film specifically. And I’m really, really interested to talk to you about that. We will definitely talk about your new film as well. But I’d like to talk to you about the influence that you had on young Chinese documentary filmmakers coming out of the Yamagata Documentary Film Festival in 1993. Is that okay if we talk about that first?

FW:

Yeah, sure.

SCM:

Great. I really appreciate that. So I’ve looked for other interviews that you might have conducted on this subject, and I haven’t found that many…

FW:

I don’t know of any. The whole question of influence is hard for me to comment on because I haven’t seen their films.

SCM:

It’s more just about understanding that period in time. I’m aware of at least some of the minutiae of this history, and I wanted to talk to you about it to see how much of it you’re aware of and how much of it maybe you haven’t heard. But obviously, in 1993, at the Yamagata Documentary Film Festival, you showed Zoo…

FW:

Right.

SCM:

…And there were three filmmakers that were there at that festival from mainland China. One was Wu Wenguang, who I believe you know personally…

FW:

Right.

SCM:

…and the other two were Duan Jinchuan and Hao Zhiqiang. Do those other names ring a bell?

FW:

No.

SCM:

That’s fine — one out of three is enough. When Wu Wenguang came back from Yamagata after seeing your films, he brought VHS tapes with him back to China. And Hao Zhiqiang, who worked at CCTV at the time, used his studio at CCTV to make copies of VHS tapes of your films and circulate them to a number of other young Chinese documentary filmmakers. When I interviewed Hao this year, he told me the story about making these copies and distributing them. And if you’ll forgive me a bit of an analogy here, but you have to understand from talking to these filmmakers, from my perspective anyway — and I think from their perspective as well — in a sense you’re kind of like the Beatles to them at that time. There’s this huge explosion of interest in your work and you see it reflected in the films from that time as well. But before I talk too much — can you tell me a little about your recollection of meeting some of these filmmakers in 1993, and just what it was like being at Yamagata that year, based on your own memory?

FW:

I can’t remember when I first met Wu Wenguang, whether it was Yamagata or if he called me up when he was in the States and came to visit me. I’d have to go over my records, because I don’t remember which came first. [Ed: It would have been at Yamagata first.] But Wu and I got along very well, and we talked; he came to visit me up in Maine when I was editing something or other, I don’t remember what I was editing… And I’m a bit ambivalent about the use of my films in China, because I would’ve preferred that they had asked my permission to make copies. I understand — they probably didn’t make too many copies — but my films are very popular in China, and I think I’ve only arranged for the sale of one there. And one thing I share in common with Chinese filmmakers is that I like to eat. So I understand all the arguments — they didn’t have much money — but I probably would have given them to them had they asked. I don’t like the idea of just making copies and circulating.

SCM:

I completely understand that concern. The thing I’m interested in now is talking just about why they were so popular in China, because I think you understand to a certain extent, but also because I’ve talked to these filmmakers… Anyway, what’s your impression of why they were so popular in China?

FW:

Well, I don’t really know. I’ve heard they were popular in China, but I’ve never…that’s about as far as it goes. Nobody’s ever told me the use they were put to or how they might have influenced them, and I can’t make any judgment about that, not having seen their work.

SCM:

Sure. I understand.

FW:

So obviously I’m pleased that they liked my films and the technique that I use. I know from the one short visit I made to China [that the technique] is very adaptable to life there. It’s adaptable to life anywhere, but… you know, I’m troubled by talking about anything that’s unique to China. But if I’m correct in thinking that filmmakers’ — independent filmmakers’ — activity was throttled for a long time and suddenly, and for a period of time, the possibility of working independently without any government control or minimum government control may have opened up. I can see why people would like this technique. You can make a film about anything as long as there’s available light.

SCM:

(Laughs) True.

FW:

And you don’t need much money if you’ve got the equipment.

SCM:

My takeaway from talking to these filmmakers about why your approach resonated so much with them is interesting because I think it actually cuts against what you use that approach for a lot in your own work. And what I mean by that is these filmmakers… you have to realize, at the end of the 1980s, which basically you’re about a 10-plus-year period into being able to even see documentaries, because of the Cultural Revolution. And, at that time, the only documentaries that they were seeing really were State propaganda, State TV. But there was starting to be a bit of a development away from that. And filmmakers, especially because of the change in technology and the more accessible filmmaking technologies, were trying to do things differently. But what’s interesting to me is I think what resonated with them when they saw specifically Zoo in 1993 [at Yamagata] is they saw in direct cinema this ability to make films that are not propaganda, but that are instead in this observational mode, and in a sense even a passive observation. Or at least it doesn’t have to be read as politically antagonistic.

FW:

I don’t think that’s accurate. No, passive observation is not an accurate description of what I do. Because it’s passive in the sense that there’s no intervention, but it is not passive in the actual way the films were made.

SCM:

Absolutely.

FW:

Because they require thousands of choices.

SCM:

Well, I think what’s so interesting is that their experience with it bore this out. So, there’s a film called The Square, from 1994. It was one of the first films that was made in China that was really clearly influenced by your work, and it was only a year after they had that exposure to your films. It’s an observational portrait of Tiananmen Square in 1994, and they’re trying to just observe what it’s like to see the police presence there and to see the reporters there. And they tried to think of this as being not politically antagonistic. But the State clearly did not see it that way. [Ed: It was banned.] And so, I think they had this feeling they could use the aesthetic as a way to not be politically controversial, and the exact opposite happened. And then you see a change throughout Chinese documentaries over the course of the 1990s.

The next point I wanted to touch on, and this is really an oral history question, but you did go to China in 1997, and you gave a keynote address at a film festival there, and also did an interview with CCTV. Can you tell me a little bit about what you remember from that visit?

FW:

I hadn’t thought about my trip to China for a long time, but I remember I got off the plane and they had a meeting arranged already, and I think Wu Wenguang was there, but some high Chinese official also, they were waiting for me. They waited a couple hours for me to arrive from the airport and go to the hotel and take a shower, et cetera, because it was a long trip. I didn’t know in advance that this meeting was to take place. And, it was naive of me, but I was struck by the sort of obvious hierarchical nature of the relationship of the people in the room to each other. But I don’t think I had anything startling to say. I talked about the way I make films, and I responded to their questions, as I would respond to yours. There was nothing obviously ideological in my comments, except insofar as the way I work is, by implication, contrary to what was usually acceptable in a totalitarian state.

SCM:

Do you remember any of the questions or what you talked about in the interview that you gave on TV?

FW:

I have no idea.

SCM:

I’d love to find that interview somewhere, but I haven’t been able to.

FW:

I know I never had a copy of it.

SCM:

And were you able to see… I think I’ve read some interviews with you where you have said that you’ve seen some of the Chinese documentaries from that time.

FW:

I’ve seen some work by Wang Bing. But only in the last year or two. And I met with him in Paris. We’ve met a couple of times.

SCM:

That’s actually where I was steering this conversation, because I talked to Wang Bing a couple months ago. He was giving a workshop at Harvard [Ed: This interviewer works at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University, where Wang Bing recently taught a workshop on documentary filmmaking]. So I have to say that I have a book project, it spans from 1989 to 2002, and Wang Bing made his first film [West of the Tracks] in 2002, which was a real departure from a lot of other documentary films that were being made in China prior to that time. And actually, it’s a departure in the sense that it’s probably the film that’s the most like your work than anything else that came before.

FW:

The shooting is very much like my work. It’s not as highly edited.

SCM:

He uses long takes in a different way, but there’s one thing that makes it more similar to your work, compared to Wu Wenguang’s films. Wu did sort of gradually move away from this, but Wu’s early work — which he says was influenced by you — is actually more cinema verité than direct cinema, because it intersperses these very intentional, on-camera interviews. Wang Bing, though, really moved away from that entirely when he started, and instead embraced the direct cinema mode.

So I want to transition a bit to how Wang Bing thinks about direct cinema — since he’s really an endpoint for me in the evolution of Chinese documentary — to how you think about it. Wang had a quote from a recent event here at Harvard that I thought was really interesting, and when I was watching your new film, I was thinking about it, and how you might feel about it. It’s a bit esoteric. He said, “in cinema, there’s no composition, only time and space.” Now I know that composition is important to you, but I do wonder, how important it is in terms of hierarchal considerations. Where does composition sit exactly?

FW:

Well, I care about it a lot. I’m making a movie and I like the picture to be as good as possible. I mean, whatever my definition of “good” is. I’m very aware of composition, both during the shooting and in the choice of shots in the editing.

SCM:

On the topic of composition, it has to be a very different way of thinking when you’re shooting in 16:9 as opposed to 4:3. How do you approach composition when it comes to framing different aspect ratios?

FW:

I mean, it’s just the way it looks to me. It’s not any kind of formal process. A Couple was shot in 16:9, but for the documentaries, I prefer the 4:3.

SCM:

Obviously a lot of your films are focused on institutions, but recent ones have also been pretty focused on the sort of space of the institution. For this film, though, it does wander, it wanders outside the institution, or maybe you consider these other spaces that it goes to an extension of that institution?

FW:

I don’t have the precise definition of institution that I originally conformed to. So that’s not an issue for me. I don’t say an institution has to be a four-story building with 22 rooms. It’s more the feel of the people. City Hall, I mean, I call it City Hall, but it takes place in Roxbury and Dorchester and Brighton, et cetera. But it’s focused around the activities of the people who work out of City Hall. And Belfast, Maine is… there’s 6,000 people, and it covers quite a large area. So I’m not wedded to the precise definition of institution. And I went outside the physical confines of the restaurants because I thought I wanted to show a sense of the system, it was important to show the suppliers and the relationship to those suppliers. And also the manufacturers of the products that they use, like the cheese or the wine.

SCM:

I think it’s interesting how it goes outside and then it comes back inside the restaurant at the end. When you were shooting all this footage, did you have any sense… I know you often find the film in the edit, I think that’s what you’ve said. But did you have any sense of the structure that you wanted here? Did you always want to go outside and then come back inside? Or was that something that came to you when you were putting the film together?

FW:

Well, obviously, when I shot the outside stuff, I thought I was going to use it. I had no idea how I would use it, or where I was going to use it, but I thought it was important to collect it and make the decision on how it was going to be used later. Because I never make, as you just said, I never make any decision. I mean, I don’t really think about structure in any precise way during the shooting.

SCM:

I think, in general, you’ve often said that you don’t like to have a lot of preconceptions going in, you don’t want to do research about the subjects to a certain extent. You want to be able to discover the subjects of the film by filming the subjects. In this case, for this film, on a somewhat sliding scale, did you have more preconceptions or less preconceptions than you’ve had compared to your other films?

FW:

No, I had no preconceptions, because I think I had eaten at a three-star restaurant only a couple of times.

SCM:

You’re ahead of me, then.

FW:

I made the original visit and then one other time. But I was basically completely ignorant.

SCM:

Since you were ignorant going into this, what were the conversations like with the restaurateurs when you said you wanted to make this film? What were the things you talked about and the guidelines?

FW:

The whole thing came up by chance because I took some friends of mine there for lunch one day to thank them for putting me up in their house (which is about an hour away from Troisgros) during the month of August, in 2020. And when César came over to the table after lunch, just as part of the routine meet-and-greet, I blurted out “I make documentary movies.” We considered making a movie about the restaurant. I hadn’t planned to ask, actually; my documentary spirit was aroused. And he said, let me talk to my father. He came back half an hour later and said, “Why not?” I discovered, a year later when I showed him the film, that his father wasn’t there that day — what he’d done, he told me, was look me up on Wikipedia. And I’ve never read what Wikipedia says about me, but I guess he liked it, so he said, “okay.” And then we corresponded a couple of times, and I went there and I met [the family], and we exchanged some letters; I waited until the spring of ‘22 to make the movie. But to go back, to be more precise about the preconceptions, I had been to the restaurant twice. I knew nothing about restaurants as I know nothing about most of these subjects before I start [making films about them]. And maybe even people think they know nothing about them when it’s finished. But what I learned is what you see in the film.

SCM:

I’ve read you say something to the effect of “the lens doesn’t change the people’s behavior.” That interview was from many years ago, so I wonder if you still feel like that’s the case? Do you still feel like, especially now — your notoriety and prestige has only risen in the decades since whenever that interview was — do you still feel like you can make these films and be behind a camera and be who you are and not have it affect the people in front of the camera and how they’re behaving?

FW:

Well, you see the result. I made Troisgros in ’22, and while I like to think that everybody’s heard of me, that’s not true. And I think the explanation is more rooted in human behavior. First of all, people like the idea that somebody’s sufficiently interested to want to make a movie. Secondly, people aren’t good enough actors to change their behavior — if they don’t want the sequence shot or if they don’t want the movie made, they say no. In my experience, it’s extremely rare that anybody says no, either to the getting of permission, or to the particular sequence. And as to whether people act for the camera, most people are not really good enough actors to suddenly change their behavior because their picture is being taken. The level of acting in Hollywood and Broadway would be much higher than it is, because you would have a vast pool to choose from. I think the issue is the same as, I don’t know whether you interview a lot of people, but anybody who meets a lot of people, in order to survive, has to have a good bullshit meter. Because if you don’t, you’re going to get conned. And certainly, when you make one of these movies, if you think somebody’s putting it on for the movie, you stop shooting.

SCM:

Yeah, that’s what I was getting at basically: Whether or not you’re still looking for those moments when people are sort of crossing into performance, demonstrating more of an awareness of the camera. Were there times on this shoot where you were conscious of that and you had to stop the camera?

FW:

No. It’s very rare that it happens, but it has happened.

SCM:

There were a couple scenes [in Troisgros]… the scene when they were talking about bullying at the restaurant and having to be aware of how they talk to each other and things like that; to me that was an example of where I wondered, “Is that a kind of conversation that they would be having in the same earnest terms that they were having it if they weren’t on camera?”

FW:

That was stimulated by a letter they received from one of the restaurant associations. They had a big meeting about that letter, but it was too long to include in the film, so I used the consequence of the letter, which was the talk of the head waiter to the staff, because it was more specific. But the restaurant association circulated a letter among, I guess, lots of restaurants in France, saying this harassment is a problem. It’s worse in some places than others, but you’ve got to be aware of it, and you’ve got to report back to us what you’re doing to deal with it. So, in no way — it was stimulated by the letter, not provoked by me.

SCM:

That’s interesting context. The other thing I wanted to ask about is the last part of the film. Obviously, every part of the film is intentionally edited by you and you care about what you’re communicating. But for the last part, I really kind of took notice of how you edited together these sequences where a lot of things that hadn’t been talked about throughout the film are now coming to the fore: The oral history of the restaurant, the awareness of the younger generation — there’s the speech that the chef gives about younger winemakers and being so impressed by the new techniques that they’re using — just this marrying of different discussions that are taking place. Were you trying to, and I know you don’t like to talk about the statement that you’re trying to make, but if you just maybe talk a little bit about editing that last part of the film, and whether or not you feel like there were any different considerations taking place there?

FW:

It was shot on different nights.

SCM:

Yeah. So it was conscious to put those things together, is what I was saying.

FW:

It was very conscious. From my point of view, every aspect of the editing is conscious. Or an effort to be conscious.

SCM:

But did you feel like, for that section, there were certain considerations different from the rest of the film?

FW:

Well, because I wanted those kinds of…I dunno if “issue” is the right word, but one of the things the film is dealing with is the transition from one generation to another. And several of those conversations that Michel has, you’ve seen illustrations of that earlier in the film. For example, where they’re talking about the kidneys and the fruit de la passion, or whether there was enough sriracha in the fruit de la passion and the preparation of the kidneys… Michel is giving a masterclass in taste, and César is there. César makes a face because he’s his father. But the face he makes, he’s also saying, “You know, I know all this. You don’t need to tell me this.” And so you get a slight sense of generational conflict there, but not a serious one, because they got along extremely well. And in the scene with the guy from the vineyard who’s turned over complete control of the vineyard to his sons, Michel then talks about how he was in the process of doing that, but he hadn’t done it yet. And now it’s been done. That conversation was related to the early one about the kidneys, and related to the one that follows it, where Michel talks about the history of the restaurant and his father and his grandfather, who in turn passed it on to him.

SCM:

Yeah, that makes sense.

FW:

It’s a little way of saying all that’s very deliberate.

SCM:

One quote that resonated with me was when Michel says: “When you have such a beautiful workspace, you can manage the kitchen without raising your voice.” Obviously a lot of people, a lot of Americans who come to watch a documentary about chefs and cooking in the kitchen, will have that Gordon Ramsey thing on their mind, and that kind of stigmatism or thinking about how kitchens are usually run. What was your impression, in terms of why the way that this establishment is run is so different than that perception that a lot of people have about how kitchens are run?

FW:

Well, I haven’t seen any of those other films. I’d heard that there was a lot of yelling and screaming in some of them. Not here, and not because I was present, but because they were very well organized. The people knew how to work together. Michel, at some point when there was some visitors in the kitchen, says we don’t have to talk very much because we know how we work together. And he says that César can convey what he wants by a gesture or the wink of an eye. So, I mean, I’d been told about cooking shows and the yelling and screaming, but I hadn’t seen them. And what you see in the film is what I found.

SCM:

When he says It’s easy to not have to raise your voice when you’re in such a beautiful place — do you take that as a certain kind of class commentary too, or not class commentary, but obviously it’s a high-end restaurant. Do you think that if you went to a much less classy restaurant in France, basically, that you would have experienced something like this? Or do you think it really is about…

FW:

I don’t have much experience, not at a restaurant. But for instance, Leo, one of the sons you see in another restaurant, he didn’t [inaudible] me either. And I don’t think there was a class thing. He was just simply saying, it’s a great workspace, and the countryside surrounding it was beautiful, which it is. You see it outside the windows of the kitchen and you see it in the shots of the neighboring countryside that I used.

SCM:

Okay, I only have one more question, which is just about people. I think you have observed people in a real-life context, but through a lens, through a camera, more than probably almost anybody at this point. Just the amount of people and the amount of films that you’ve made and the amount of time that you’ve been making these films. Are there certain types of people that you recognize that you gravitate toward? And of those types of people, do you see yourself in them, or do you see them more as someone very different than yourself? A very different type of person?

FW:

Well, I mean, I resist any generalizations, obviously, about people, but I think I probably gravitate toward people whose work I think is similar to my own, whether it’s actors or dancers or the Troisgros family, because I think they’re artists in every aspect of their work. But it’s not only concerned with the taste, but the look. [The chefs here were] very concerned about plating. One of them always inspected the plate before it left the kitchen to go to the dining room, and if a strawberry was a 25th of an inch off place, they had tweezers and moved it, so that the design on the plate was as attractive as possible. And at one point, Michel says to one of the sous chefs, you have to think you’re arranging flowers. And he’s talking about arranging John Dory fish.

SCM:

I left the film really craving John Dory fish.