Some say the banners of John Talbot flutter still, upon the fields of Castillon. But you did not stay to witness them. Honorable demise was not in your character. So you threw down your sword and buckler, tore off George’s insignia, and sped into the wild. Days you straggled — toward the English Gascony. It was not for you to know old John Talbot was dead, and Gascogne French. Carrion-birds flew against your route; it seemed wise to contradict them. But you were no woodsman. Stumbling about the forestry, some spirit grabbed you by the ankle. You tumbled down, deep down, into the earth. All gloom, dark, the echo of tumult. It is now — only now — that your mind first strayed to the profound. That here, in this new hell, you should meet your final end. But you were wrong — this hell was not new. A flint and tinder gave you some light. Images were scrawled on the walls; horses, stags, a bear. Other, devilish creatures too. You wandered on, as though taken in trance. Minutes wind about hours. In the dimness of the cave — you knew now it must be a cave — you saw it at last. To the left, a rhinoceros — though you did not call it by that name. On the right, a bison. Below, some kind of bird. And in the midst: a figure you did not quite recognize. He seems both man and bird. He is splayed upon the ground. You felt akin to this man, or frightened of him. A deep foreboding rattled your breathing. But you could not look away.

So came the unfortunate man-at-arms to the cave of Lascaux, seeing before him paintings some 16,000 years older. But the nature of what saw spoke of a time far deeper. In the ancient days, before tilled fields, it was in animals that people shaped their vision of the world. Before ritualized reverence of the seasons, or the weather — both of which are essential in the management of crops — animals held the central fascination of early humanity. They were life, in that they were food. They were death, in that we were food. Of the many things non-human upon the earth, it was they that seemed most familiar. The Mi’kmaq, indigenous to Canada, are supposed to have a saying: “In the beginning of things men were as animals and animals as men.” A hunter often comes to imitate his prey: he lives among them; eats their flesh; drinks their blood; wears their skin. In the most ancient religion, or magic, the gods were not men, but beasts. In the most ancient art, images of animals far outnumber those of people. Perhaps we could see in the animal a readymade metaphor, or abstraction; perhaps in those starlit nights, we did not think ourselves as predominant, but a much smaller instrument in the great music. Birds have ever featured in these early reflections of the world. But perhaps their most abiding association is with spirit — with soul. As messengers that go into some beyond; or else as purveyors of that beyond. Death. Either portended or itself embodied. We may think to corvines — to crows and ravens — but many birds take this association. Cuckoos, whippoorwills, curlews, robins, wrens, owls — all have signified that final doom. The mystery of deep time survives. Perhaps that inconstant lackey of John Talbot would have recognized the signs. Our own culture has made no great break with its animalist roots. Still we see in the bird some spiritual device, or a representative of that unknown country. Twice, simultaneously, has the American cinema staked such a claim in these past months. In both The Crow and Tuesday do we encounter an ornithological emissary of the dead; ignoring all intermediaries, I will draw a line directly from the Birdman of the Lascaux cave to these films. The one implies the other.

After some thought, you identified the scene. The Birdman has thrown his dart, and disemboweled the bison. But his folly was hubris. The bison has knocked him down. He is struck dead, and rigid. He is not merely erect — though, certainly, he is erect — but taut in all his limbs. The moment of extremis was one of ecstatic defeat. In an act of bleak defiance, the rhinoceros defecates. But the bird below the Birdman appears sanctified. The spirit, in the midst of violent undoing, will persist. You thought then to Castillon, and the fluttering banners.

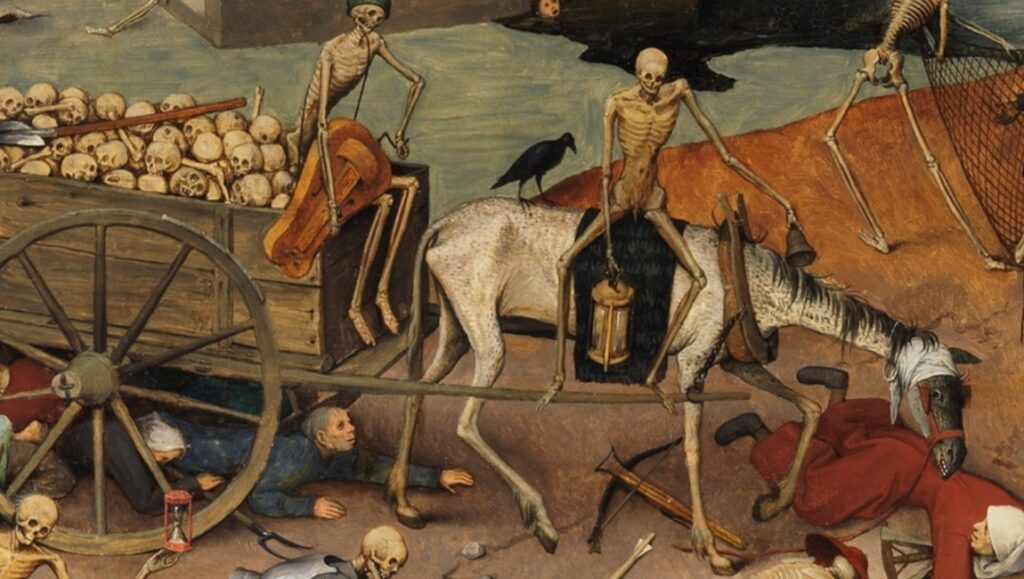

The Crow begins, after its credits sequence, with a pair of animal images. Eric arrives home to find a horse caught in barbed wire. Crows circle above. Death weaves into every association. One shot is remarkable: a closeup of the horse’s eye, in which we see a reflection of both Eric, and his halo of crows. We might reduce the image in a series of ways: the horse is dying (which means death), and the horse is white (which means death); and above fly the crows (which mean death). And then the eye: a surface that both perceives and projects. The horse sees Eric, and we see Eric in the horse; and in that gloomy reflection we see Eric and the crows made into a single, inset image. We cannot yet prise a narrative from these many associations. We know only that death has visited this boy; that death has marked him. The film takes its next phases conventionally: the grim (he must be grim) teenager falls in love, only then to meet death once again. She is killed; he is killed. Both thrown into the river, or so we might imagine. Thereby they meet another attribute of the crow. These birds, and ravens (with whom they have essentially interchangeable qualities), portend flooding, and rainfall; they can lead a person to water, or call the water to the person. It seems appropriate that the bird most synonymous with death might also relate to water; which is to say, can relate between two states, and the motion between. Being submerged — going under — finding oneself on some other side. Eric is spared, or spared in a manner of speaking. He finds himself in a liminality — a damp, abandoned train station — where he is tasked with avenging the people that killed himself and his lover. He is not, in this respect, freed of death. Rather he is to become death. In a later scene, the ritual is made literal: a crow swoops down and into his body; he is now the Birdman — an envoy from the other side, in whom exists the animal-spirit of that attribute. He becomes the omen: a man, representing a bird, representing death. He is the crow perched on a wretched horse, as Bruegel painted long ago.

It was to Bruegel your thought now turned — or it would have been, had Bruegel yet been born. You looked again at the composition, and saw something different. You saw the legendary reversal of the hunter: the Birdman is defeated by his prey. The archetype gone awry. But — and you thought to the hills and woods you traipsed just yesterday — all else appears unbothered. The bird perches on its branch. The rhinoceros looks elsewhere, and defecates. Life goes on. The tragic doom of the Birdman is just one fragment of a larger image, and it is not that which determines all else. Death — disembowelment — defecation — erection — indifference. These seem all the natural constituents of a mercenary world.

In Tuesday, we also begin with an eye; or rather, the cosmos as contained or reflected within an eye. It is a wider image than in The Crow — more grandiose — and yet comes to a similar point of emphasis. As we zoom out, we find the eye to belong to another kind of bird. It is nestled beneath the tear duct of yet another eye. There, where the waters spill. Darkly feathered, but not a crow. In fact, much the opposite. A macaw — a bird that does not come much to symbolize death, save for its sickle beak. The Bororo tribe believes macaws to be messengers from their ancestors in the beyond; this is about the limit of the macaw’s association with death. Otherwise, parrots are probably more famous for dying than for death. After all, they live a long while — the death of a parrot is momentous. Charles Alkan wrote a death march for a parrot; Rumi composed a story in which parrots seem to communicate by pretending to die. Indeed, the parrot’s pretend-death is what frees it from its cage. There is a metaphysic in that kind of dying. But I suspect the contrariness of the macaw with death is perhaps the reason for its choosing. When it is washed in the sink, the darkness of its feathers is washed too. He stands arrayed in his rainforest colors, not grim but beautiful. All of which indicates a somewhat more humane reading of the reaper — not the violent avenger of The Crow, but a necessary function of the turning world. The narrative is then one of resistance. A kindly victim shares a joke with death, and so he delays her passing for a little while, so that she might say her goodbyes. When the victim’s mother discovers this clemency, she attempts — vigorously — to destroy death. She clobbers death with a textbook, sets death alight, and then eats the charred remnants. In so doing, she too becomes the Birdman. She too must take on the aspect of the bird, and serve its purpose. She must, also, become death, and restore order by the swinging of a scythe. This bird, too, leads her to the water: it is by the sea that she comes to understand a life spent on the edge of the unknown, ever delaying the plunge.

Again you found yourself disconcerted. You did not see a mercenary world, but a fine comb of symbols. Each part seems significant, within and without the whole. Here the Birdman represents the virility of death and rebirth. The spear pierces the bison through its bowels and out of its anus — or through its anus and out of its bowels? The direction of process is scrambled, inverted, confused. Beneath the Birdman is a totem — not unlike the bird through which the Annunciation is so often depicted. And thus those six orbs, not the projectile defecation of a rhinoceros but rather esoteric imagery that feeds into a shamanistic apparatus. Note the spear thrower — discarded beneath the Birdman, and the angle it produces against the spear, and against the perch of the bird totem, relative to the Birdman, and then the six orbs. The bison, the thrower, the spear, the totem, the rhino, the Birdman — six elements. This is a cosmogony; an arrangement of systems; a map of the stars.

The point of convergence between The Crow and Tuesday is then a curious point of perspective — of the seeing, reflecting eye — insofar as both films effectively take the avian point of view. In both, the birds serve as envoys of death, and in both are the envoys embodied in the protagonist, and in both situations the requirement of death is positive and necessary. The films, each in their contrary aspects, represent an essentially pro-death narrative. Or to be less glib, they are films opposed to immortality; opposed to the total absence of death. In The Crow, Vincent Roeg has made some bargain with the devil: if he supplies innocents to Hell, he might live forever; he must pervert the balance so that he might evade what should be inevitable. Eric is therefore tasked with the enforcement of mortality: he must reassert the precedence of death and therefore set right the metaphysical design. He becomes the inversion of Roeg: a deathless man whose ultimate objective is (for Roeg and, in the way he has arranged it, himself) death. He can only be sated when the two immortals are together undone. Tuesday imagines a scenario in which death is vanquished: in which no person or creature may die. Immediately, an apocalyptic haze falls upon the world: birds banging their heads endlessly upon windows (another infamous bird omen), a swarm of deathless flies, men without legs hobbling about. However grim the visage of death may prove — in either case — a universe without death is immediately perverse. And yet in death is implied resurrection. Eric decides he will change places with his beloved; he will take her place in the water — passing into the other world — so that she might live. In Tuesday, the perspective is once again inverted: the daughter dies, as she must, but in her dying she ensures that her mother must live. No longer will Eric, or the mother, linger on the liminal shore, but firmly step either into or out of the waves. The birds— the crows and the parrot — are not then foreboding. They are restitution. They are the necessary order. They are the still point of the turning world. In all the warp and weave of time, the birds look on.

And you looked again. Perhaps it was the rhinoceros that gored the bison, and the Birdman who paid for it. Perhaps the Birdman is no man at all, but a man wearing a mask. Perhaps the man is screaming. Perhaps, in this slew of image, no true thing can be discerned; a scattering of disconnected coincidence, that just so happens to appear simultaneously. Is there, you thought, an absolution hidden in this picture, that so long has dwelt beneath the fields of France? Your kindle flickered, grew dim, then out. But you went not with it. You stumbled about, you felt the curve of those ancient walls, as long your ancestors did. You found the light; you clambered out; a low sun gleamed. Soon came the stars wheeling over, as you made opposite your first march. Now you did not defy the carrion-birds, but followed their flight. Night gave way to day; day to night; in the wilderness time is assured. Then came you to the field. The carcasses were stripped and pilfered; the rot had become stench; the birds did not quit their feast. And still flutter the banners of John Talbot, upon the fields of Castillon.

Comments are closed.