Traditionally, dramas dealing with characters moving on from relationships follow a three-part structure: the chronicling of the youthful highs of the first passionate relationship and circumstances leading to its dissolution; the devastating aftershocks of that dissolution (with the former either being deployed linearly or emerging as a flashback after establishing the latter); and finally, the eventual overcoming of the paralysis induced by the loss, either through filling the void with a seemingly disparate substitute, or, more “maturely,” shaking off the past and the romantic ideals associated with it through a change of outlook, with some films even sappily doubling down on this line by injecting a renewed vigour for life in its protagonist through shopworn truisms. Wong Kar-wai, on the other hand, chooses to luxuriate in this very paralysis which received (cinematic) wisdom has counselled against. 2046 (2004), his film made on the heels of In the Mood for Love (2000), keeps circling around the events of his most acclaimed film, and more implicitly, his oeuvre itself. To many critics at that time and even fans of Wong, this is nothing but an admission of defeat, a crippling inability of moving on from a “storied” past, and thereby being nothing more than a pretty pastiche, one which people can readily get behind for its beautiful surfaces but can’t endorse as a work of a “mature” artist. But the paralysis induces questions which we readily brush aside in our forward-looking efforts to move on, narrative and relationship-wise. How do we lunge into the unknown future without dimming the intensity of the passionate past? Or, in the words of Anna, one of the protagonists in Simone De Beauvoir’s The Mandarins, “Of what use was my impassioned remorse if it was ordained that I would one day awaken in indifference?”

Though 2046 is itself centered on the aftermath of In the Mood for Love’s unfulfilled relationship, Wong knows that the above questions are not just a matter of love and romance alone, but those which can be easily extended to both aesthetic and political spheres, although Wong deals with the latter more obliquely. Excavating a memory also projects it into the realm of possibility, molding the world in the misshapen memories of the past that also spark visions of the future, and it’s this very collision of the idealized and imagined pasts and futures that distorts the interactions with the present. Our repeated viewing and reimagining of our favorite movies and cinematic memories make us follow the trail of dust they leave behind, collecting and reshaping them into kernels of aesthetic modes, possibilities, and directions. To a passive observer, this circularity is merely an elegant metaphor of an ouroboros, beautifully surmounted but essentially saying nothing new. For Wong, a serious consideration of the slightest tinkering opens up pathways and threads that force one to confront how they think about cinema, and by extension, life itself.

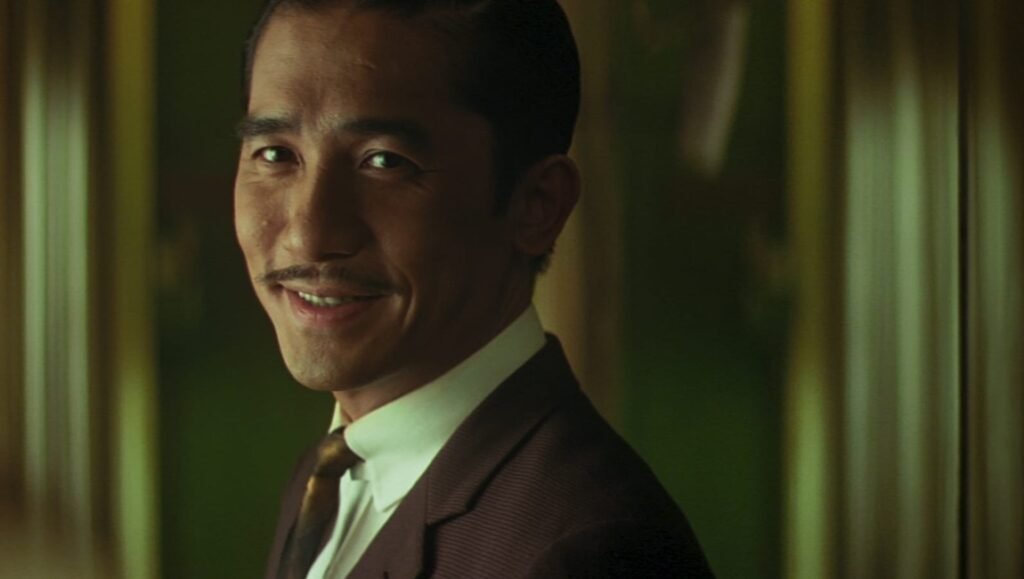

Picking up from where the final scene of In the Mood for Love left off, 2046 follows the attempts of Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung) to burrow deep into his sealed mudhole of memories in Angkor Wat, inhabiting it and dragging it with him into the future while allowing a rotating roster of beautiful women to seep in through the cracks. Drifting aimlessly in Hong Kong and Singapore, Chow wallows in the lost possibilities of his seemingly unconsummated affair with his neighbor, Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), remaking the women he encounters in the image of that memory. But what do we make of these women, who appear to be mere variations of the same woman, Su Li-Zhen? (The character played by Gong Li, nicknamed “Black Spider” and fetishized by Chow and Wong by focusing on her black glove “a mystery with no solution” — as a symbol of her unmentioned, yet checkered past, is also called… Su Li-zhen.) Are they mere projections of Chow’s tortured memories onto entirely new bodies, eventually disappointing him as they aren’t the “real” Su Li-zhen? Each of them is endowed with their own attire and hairstyle, with Wong allowing only two of them, Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi) and Wang Jing-wen (Faye Wong), the flexibility to change clothes. The other Su Li-zhen is forever condemned to be draped in black, her voided attire and glove preventing access to the past. Bai Ling’s hair is intricately knotted and tressed even at home, with Wong permitting only some of her strands to loosen after sex. Carina Lau’s Mimi/Lulu, reincarnated from Days of Being Wild, only gets a new set of clothes as a supporting character in the fiction-within-fiction 2046, the sci-fi fantasy story written by Chow where people go to retrieve lost memories (the hole from In the Mood for Love crops up here, except that it’s a retro-futuristic art object that is open and never sealed) and unlock answers to pressing questions of the past.

This fiction story features Wang Jing-wen and her Japanese lover (Takuya Kimura) as protagonists, with the Japanese lover being the boyfriend who falls in love with the Android Wang, whose engineering flaw results in a delayed response to emotional stimuli. Both protagonists are reimagined through the prism of Chow’s interactions with and burgeoning love for Wang, along with details of her struggles in obtaining her father’s approval of her Japanese lover. Wang gets a makeover and new hairdo like Mimi in this story, but her identity is always complicated by Chow’s interest in her as an unattainable object of someone else’s desire, yet another echo of his relationship with Su Lin-zhen. The shattered shards of the fated love affair from In the Mood for Love are grafted onto these new bodies, with Chow and Wong erecting shrines for each of these fragmented archetypes, replete with synchronicities, doublings, and rhymes from Chow’s torrid imagination and memory. Just like a shrine, their appearances are tightly controlled, and venerations are offered in the form of incantations manifesting as a theme song for each of the four women framed against the dilapidated settings of their surroundings. As has frequently been the case with Wong, the grunge is glamourized through his lighting and the lush costumes of his women.

But the actors playing these women are much more than mere presences, and their interactions with Chow are never devoid of passion. This dichotomy frustrated some critics, as the women are insufficient as characters, yet their performances and Wong’s attentive, reverent framings led some of the film’s champions to elevate them to the privileged status of a CharacterTM. As Adrian Martin writes in his perceptive piece, discussions on cinema are seldom taken seriously without recourse to the liberal humanist artistic touchstones — plot, narrative development, and character. He described these women more as “vivid figures” embodying “lyrically condensed states,” similar to Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, and I am more inclined to agree with him. These women indeed function as an extended processing of the memories of Su Li-zhen by Chow in individuated fragments stretched across different temporal planes. This naturally raises questions, especially when we consider women’s continual relegation as objects of the male gaze. But Wong renders these figures far more alive than their highly subjectivized manifestations, existing both as fetishized objects and something beyond that.

An overarching emphasis on Chow’s perspective fails to reckon with Wong’s formal explorations, which constantly complicate our perceptions and ideas of these vivid figures. Wong’s tight, claustrophobic framing of these interacting bodies tends to obscure and disfigure more than reveal, with walls, opaque reflections, darkened heads, and voided out spaces thrust into the frame, almost oozing from the black bars holding the images together. Although we are left with little to no doubt that the paralysis belongs to Chow, these compositions appear as collisions of two different subjectivized spaces, almost as if the two figures are constantly reimagining the other through their own fractured lenses. The revival of Mimi from Days of Being Wild, where Tony Leung played a minor role, points to this very complication, where an earlier figure dealing with the break-up/loss of her lover is brought head-on to Chow brooding over his lost affair. Multiple threads and conceptions might converge in and around the number, 2046, which was the room number occupied by Chow and Su Li-zhen, but there’s always the sense that these threads are slipping from Chow’s grasp, assuming a life of their own.

We see Chow gazing through slits at women living in the hotel he’s in, but Wong seldom follows his line of sight, drawing attention instead to the women’s stylized tics and off-screen sounds. The abundance of visual rhymes introduces variations of their own, and in some cases, these variations almost appear to be triggered by the women intruding into Chow’s fantasy, as is the case with the first black-and-white shot in the film involving the its most acclaimed section: the affair between Chow and Bai Ling. Wong allows this black-and-white visual to rhyme with a later sequence involving Su Li-zhen, where he focuses more on the emotions expressed by Chow, his longing for the very moment, even as Su Li-zhen appears a lot more detached. The first black-and-white scene, in contrast, lets Ling’s emotions take center stage, with Chow’s clasping of her hand assuming significance, forming a mini-visual rhyme with Wong’s other hand shots involving changing objects and gestures. If these figures are manifestations of Chow’s consciousness, Wong also teases the possibility of the reverse being true, rendering these fetishized figures far more “alive” than a mere fantasy. These reversals threaten to veer away from Chow’s spiraling toward his lost memory, rendering the emotional devastation of the figures’ disappointments all the more powerful when Chow successfully returns to his center of the spiral.

Considering the extended production saga of 2046, it wouldn’t be too surprising to find out that Wong had fleshed out more detailed narratives for each of these relationships and their distortions through colliding memories. The director appears to be far more fascinated with the idea of paralysis induced by passionate affairs in the abstract (meant as a compliment), roping in his own films and characters as fodder to explore this very feeling and cinematic form. Wong’s skirting of Hong Kong politics led some to interpret that the film itself eschews politics altogether to focus on the affairs of Chow, but that would be to disregard his title, which clearly references the year when Hong Kong’s status as an independent entity ends, and to the ways in which he worked the Hong Kong politics into his form, however obliquely. The grainy found footage of the ’60s riots in Hong Kong contrasts sharply with the claustrophobic lyricism of Chow’s romantic overtures, but this ties in with Wong’s exploration of paralysis. His figures might eschew the politics, but the politics, especially the economics, constantly threaten to destabilize the affairs of his figures, with transactions even directly figuring into his relationship with Bai Ling. Even as the film moves into the future through its sci-fi setting, this economic anxiety remains, and while this might have led to the glib conclusion that no political change is possible in a different film, Wong zeroes in on the idea of being stuck even as the surroundings appear to change. This duality of paralysis and difference motivates the entire workings of 2046 — the blocking, the larger use of static compositions (as opposed to his more herky-jerky mobile works), and the lingering power of the actors’ emotions, which we sometimes mistake for character development. If Wong’s figures and settings continue to challenge us, it is because — and I include myself here — of our inability to grasp the potentialities of cinema and how it moves us, forcing us to rethink our frameworks of understanding even when looking at the seemingly totalizing categories of fiction and genre.

Comments are closed.