“If a man die, shall he live again? All the days of my appointed time will I wait, till my change come.” — Job 14:14

Shoah is the final boss of mainstream cinephilia: the most widely known of the least seen epic-length movies ever made. This writer — a Jewish cinephile who received the Criterion Blu-ray as a Hanukkah gift in 2013 — has owned it for nearly 12 years, and only now, on assignment to commemorate its 40th anniversary, actually sat down to watch it. But what does it mean to watch Shoah in 2025, when the world is yet again on the verge of fascist ruin and the State of Israel has itself systematically slaughtered the people of Gaza for over two years? The way we talk about genocide has changed irreparably in the aftermath of October 7 — where does Shoah fit into that conversation?

It’s important to shake off the wooden, histrionic adjectives typically ascribed to it and deal with the movie as it is. Words like “towering,” “monumental,” and “masterful” won’t do — they ossify the work, fossilize it. Shoah is not a fossil; it’s not even the definitive documentary about the Holocaust. It goes deep rather than wide, exploring only through contemporaneous interviews and footage the mass exterminations of Jews at Chełmno, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Treblinka, with an extended coda dedicated to the Warsaw ghetto, and it has a surprisingly small interview pool for a film that runs nine and a half hours: dozens, true, but not hundreds. No, Shoah is not an encyclopedic be-all-end-all oral history, but a breathing, organic thing: an inquiry.

The Holocaust became history as soon as it ended. “No one can recreate what happened here,” one of Shoah’s subjects says. “No one can understand it.” That hasn’t stopped the entertainment industry from trying: countless books, movies, TV shows, musicals, and plays have set out to dramatize it. As such, it has withered into the shape of an idea rather than a real thing that really happened. Shoah brings the Holocaust down from the level of the intellectual, where it goes to die — or worse, to become manipulated — and to the realm of lived, felt experience. A Polish conductor is paid in liquor to run the train to Treblinka because otherwise he couldn’t stand the stench of dead and dying Jews. A Jewish woman feels guilty for hiding when everyone else she knew perished, defying “a fate that was our destiny.” A Sonderkommando resolves to die and walks into the gas chamber he is forced to operate, only to be implored to live and bear witness by someone about to be gassed. There’s no end to the number of devastating observations shared by those who were there, but it would be impossible — and foolish — to recount them. The movie is there to be watched; Lord willing, it always will be. It would be more productive instead to honor director Claude Lanzmann’s aesthetic achievement, which has perhaps been neglected in favor of his journalistic rigor.

Visually, Shoah has more in common with European art cinema of the late ’80s and ’90s than it does any other documentary, and its footprint is larger than we realize: Krzysztof Kieślowski’s capacity to find the infinite in the human face; Bela Tarr’s demented long takes; Michael Haneke’s dramatically motivated use of CCTV/surveillance footage — they all find their genesis, or at very least a strong affinity, here. Some interviews will be conducted in a two-shot, but instead of zooming into the speaker, Lanzmann will zoom into the listener, studying their solemn disposition. Landscape shots will undulate, back and forth, back and forth, like someone reciting Kaddish in temple. Interviews with Nazis are conducted surreptitiously, their plump faces hovering in jittery black-and-white — more like ghoulish blue — tape while we watch remotely from a nearby van as they freely offer reflections on the camps they managed. And buildings look alive: farmhouses, factories, and especially a painful slow track to the entrance of Birkenau — old, grimacing, stuck in a frozen scream. It’s borderline psychedelic stuff, and Lanzmann negates the compulsion to dramatize the Holocaust by putting us there more totally than any piece of drama could.

Some moments land with a staggering Wagnerian power: we drift down a river illuminated by a blue and orange dusk, a screen of trees in the distance; stones — monoliths, sharp and jagged — jut out from the earth as people describe their experience of surviving the camps; and in one daring cut, Lanzmann moves from harsh winter to gorgeous early summer as someone describes the process of cremation. There’s a taking back of Germanic scope in Shoah, and a rich irony in the fact that a French Jew made cinema’s closest corollary to the Gesamtkunstwerk. It’s a truly modernist movie, if we accept Mark Fisher’s definition of a modernist work as something “innovating cultural forms adequate to contemporary experience.” Shoah’s twice-a-marathon-length, its elemental images, its Socratic nature: it meets the moment. It meets 1985’s moment, and it meets ours.

Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, who was born in Austria and fled to America as a child in 1938 — you can hear the light Bavarian lilt in his voice — makes several pointed appearances in Shoah; he’s the only expert to appear in the film. He offers reflections on the systemization of death, and it’s remarkable how closely some of the genocidal steps Nazis took against Jews resemble those Israel has taken against Palestine. “People who are expelled can yet return, but people who are dead will not reappear,” Hillberg intones. It’s like he’s speaking today, and his comments — along with those from both perpetrators and victims — help us understand what genocide actually is: how it hides in the shadows of ambiguity and bureaucracy, and how it’s carried out slowly, by normal people, some of whom are well-intentioned. One of the Nazis interviewed — the only one aware of his being filmed — admits how awful conditions were in the Warsaw ghetto, which he helped to run. He only saw it twice; the rest of the time, he pushed paper at his desk. “We, at the Commission, tried to maintain the Ghetto for its workforce,” he says. “We did our best to feed the ghetto, so it wouldn’t become an incubator of epidemics.” Lanzmann cuts from the Nazi’s comments to a forest of graves. If we pay attention to Shoah’s lessons, we learn that never again really means that: to anyone, anywhere on the planet. Today. Right now.

The deeper into the movie one gets — and at times the experience of watching it truly does feel like spelunking into a bottomless cave — the easier it is to see that anyone who survived the Holocaust did so only because of sheer dumb luck. With about an hour left in its first leg — the film is split into two parts, First Era and Second Era — Lanzmann reads from a letter written by Rabbi Jacob Schulmann of Grabow, Poland, detailing Jews’ death by gas or gunfire. At the end of his letter, Schulmann begs for help from God, the creator of the universe. “The creator did not help the Jews of Grabow,” Lanzmann concludes as he closes the book the letter is excerpted from. Lanzmann’s response suggests pure nihilism, but from this groundwork he builds a solid testament to the everlasting value of humanism. In a long passage following his recitation of the letter, Lanzmann interviews villagers of Grabow about their relationship to Jews — what they felt about them, whether they miss them. In the distance, Lanzmann squeezes in small portraits of Grabow’s people. Children hop in a circle, sunlight dancing in their hair; men watch the day pass by on porches; women sit pensively at their windows. Shoah’s greatest revelation is both tragic and affirming: life goes on after genocide.

As First Era approaches its conclusion, Lanzmann brings survivor Simon Srebnik back to Chełmno, where as a child he roamed the town in chains because the Nazis kept him alive to sing for them. What follows can only be described as a gift from God, an impossible-seeming stretch featuring some of the most moving filmmaking there has ever been, documentary or otherwise. With only a few cutaways, Lanzmann trains his camera on Srebnik outside the town’s church the day they celebrate the birth of the Virgin Mary. The villagers remember him, and they’re happy to see him. The crowd gradually metastasizes; the frame can barely contain it. They shout and explain what happened while Srebnik looks on, stoic. The specter of genocide looms larger in this sequence than any other because it offers in capsule form how history is metabolized in the present, and how genocide’s victims can be marginalized before our very eyes. Villagers argue with each other about what happened, and when. One man, subconsciously mirroring Srebnik’s facial tics, moves to the front and shares an anecdote about a rabbi who, he claims, believed the Holocaust occurred as expiation for the death of Christ. At the very end of the anecdote, Lanzmann zooms in on Srebnik. Srebnik meets the camera briefly, but as it gets closer, he averts his gaze.

Special attention should be called to the quality and the breadth of the subtitle work here. Shoah is a work of polyphony — there are a lot of people talking, and most of the time it’s over one another. Miraculously, it’s all coherent because of the subtitles. Polish, Yiddish, German, French, Hebrew, English, Italian, Greek — Lanzmann spends much of the movie’s runtime speaking to interpreters, and there’s a deep melancholy in watching him try to know, using the paltry tool of language to convey the unspeakable. His images have to compensate for the gap in meaning where words won’t suffice.

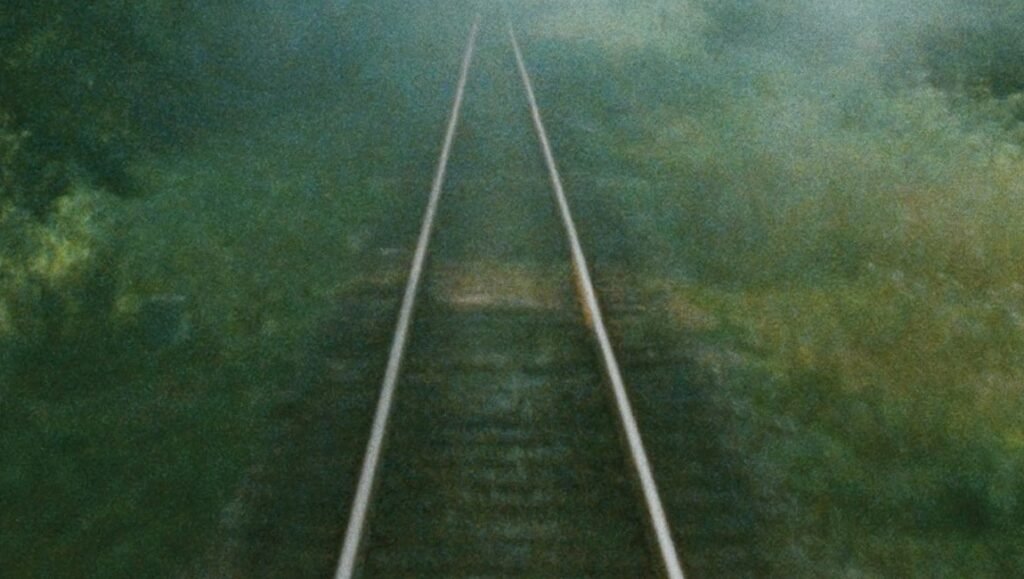

The train is the closest Shoah gets to having a central motif. Sometimes we’re in the train, other times we are the train, but we’re always hurtling, moving forward. A movie like Shoah — long as it may be — is merely a pit stop on the bullet train of history we find ourselves riding, and we’re only moving faster. As of this writing, there’s a delicate ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, but if the goal is to prevent future holocausts, the work is really just beginning. “Extermination isn’t so simple,” Lanzmann says. “One step was taken. Then another, and another, and another…” The final image in Shoah is of a hulking train, more imposing than any we’ve seen before it; it dwarfs us. In our present day fracturing of reality and truth, it might seem like this train will go on forever, but right before Lanzmann cuts one last time, there’s a crack, an opening. Shoah is that crack: an invocation — a prayer — for us to slow down, to sit with history, and, ultimately, to understand our shared past and live with a renewed sense of each and every human being’s basic dignity. “Making this film was a long and difficult battle,” reads text that opens the movie. The battle was won, surely. As for the war? That remains to be seen.

Comments are closed.