Our first dispatch from the 2019 BFI London Film Festival takes a look at an eclectic array of films both major and minor on this year’s festival circuit, including: big ticket items, Harriet (from director Kasi Lemmons) and The King (from David Michôd); outre Holocaust film, The Painted Bird; a trio of genre entries — Little Joe, Deerskin, and Saint Maud; and a pair of French films, one from an established auteur (Francois Ozon’s By the Grace of God) and one from an on-the-rise duo (Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau’s Don’t Look Down). Check back later this week for the second of three dispatches we will be publishing on the festival, and make sure to visit our recent Toronto Film Festival coverage for takes on the many LFF films we’ve already tackled.

Harriet

Ever since Eve’s Bayou, Kasi Lemmons has foregrounded the need for black adolescents to realize the importance of their influence and existence in a society fundamentally unjust to them. This specific thematic concern may situate her as uniquely qualified to tell the story of African American liberator Harriet Tubman, but breaking free from the familiar beats of its adversity narrative presents its own barriers for Harriet the film. Dubbed Minty, the young Harriet Tubman (played as an adult by Cynthia Erivo) grew up as a slave on a farm in Maryland, and the film begins with her initial escape from slavery and proceeds all the way until her eventual status as a freedom fighter by means of the Underground Railroad. The early years of Harriet’s plight indeed muster a profound emotional resonance, but one welcomes the point at which she shifts into Highwaywoman mode, when there is at least an attempt to politically contextualize the true-story developments. While much of the discourse seems a bit tame and unspecific compared to something like Lincoln, for instance, Spielberg’s film had less to contend with than Harriet, which has to marry its complex sociohistorical significance with a more emotionally wrought personal narrative and altogether disparate point of view. Lemmons does an admirable job, but as both political discourse and as a story of overcoming injustice, Harriet is less remarkable than it should be. More interesting elements of Tubman’s later life, relegated to captions in the closing credits, are left unexplored, while the relationship between she and her slave master Gideon (Joe Alwyn telegraphing a thoughtful if rigid view of masculine inadequacy) feels more than a tad forced. The standouts lie in the work of two established, consummate professionals: the legendary John Toll brings a real flair to the film with his painterly compositions, while Erivo herself gauges Harriet’s arduous arc supremely well. Although this effort from Universal should serve as encouragement that major studios can still greenlight important adult dramas that speak to and about real people, Harriet is more of a serviceable tribute to its subject’s heroism than a rounded exploration of her person and legacy. Calum Reed

The King

At first glance, adapting a story about the seat of privilege that is the throne might seem like an unexpected move for Australian director David Michôd — whose 2010 film, Animal Kingdom, is about working class Aussies turning to a life of crime to get out of poverty. Michôd’s The King, though, moulds Shakespeare’s Henry V into the story of a man drawn into dangerous moral territory, which turns out to be a snug fit for the filmmaker’s brand of hypermasculinity. Co-written by Michôd and Joel Edgerton, the prose of this adaptation retains a level of elegance, but there’s also an emotional accessibility to the film’s approach. Unfortunately, The King is inconsistent in terms of its drama, leaning into a slow and ponderous tone in its middle section that dulls the intense self-seriousness of its other passages. Hollywood’s dauphin du jour Timothee Chalamet also seems an oddly fragile fit for the role of Henry: there’s a fight scene towards the beginning of the film that hardly shows off any actual, physical prowess. And yet the actor is highly capable of selling the gradual sense of decay that eats away at this antihero’s sense of nobility. Which is to say that his performance is far more effective than Robert Pattinson’s, whose thick, sleazy French accent recalls the sort of one-dimensional villainy of early James Bond movies. It’s a testament to the universality of Shakespeare’s themes that filmmakers still believe that their own reinterpretations of his work can add something to the discourse. But there ultimately isn’t much evidence that The King accomplishes this. Michôd serves up yet another big-screen adaptation of this very familiar tale, with only modest variations. Calum Reed

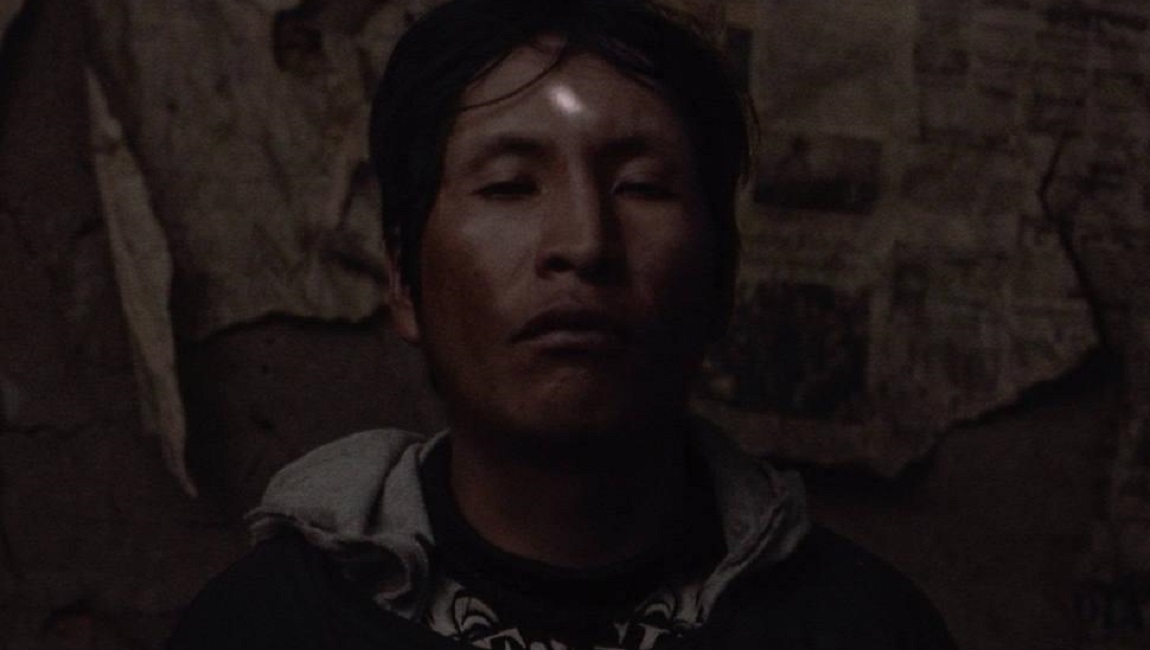

The Painted Bird

There’s something to be said for the ornate resolve of Václav Marhoul‘s punishing period drama The Painted Bird, a film that has is roots in modernist literature and certainly looks and feels as if it could have been made sixty years ago. Adapted from the controversial 1965 novel by Polish author Jerzy Kosinski, The Painted Bird chronicles the gruelling misfortunes of a boy pushed from pillar to post in the days leading up to the Nazis’ occupation of Eastern Europe, following his encounters with the many deplorable people who take him under their wing. The Painted Bird is fairly narrow-minded in its attempts to shock, employing depictions of animal cruelty (no less than four animals are brutally murdered) and scenes of human mutilation the likes of which might make Tom Six fans shudder. The titular metaphor of the painted bird, however – literally destroyed by a flock of its own kind — is a wonderfully effective one for what Marhoul is attempting to convey about a lack of humanity, particularly during wartime. The film has aspirational motivations to Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) in that it portrays a figure’s suffering through his many “caretakers,” yet lacks as poignant an emotional center, refusing to personalize the boy until later scenes (his name is withheld until its finale) when a rather strange veer into sentimentality feels unearned. Still, while it is fair to say that Marhoul has crafted quite the ordeal, his stark black-and-white imagery and overall formal ambition is really something to behold. Throughout its near three-hour running time, the film never labors — for its atmosphere alone, this is stirring and absolutely must-see viewing for fans of bravura arthouse filmmaking. So even if its piledriving brutality makes it the sort of bloodthirsty guignol likely to distract from the more profound elements of the human condition it discusses, one can’t help but admire The Painted Bird for its coolly antagonistic mode of majesty all the same. Calum Reed

Little Joe

The films of Jessica Hausner can be maddeningly opaque, but obfuscation is a feature, not a bug. Her newest film, Little Joe, makes a fascinating double feature with 2009’s Lourdes, a film that also takes a fantastical scenario and grounds it in the quotidian. In fact, Little Joe could be considered a secular version of that earlier film’s exploration of a deeply religious phenomenon — namely, how do we respond in the face of something ultimately inexplicable and unknowable? To even describe the plot of Little Joe is a spoiler of sorts, as calling it a riff on Invasion of the Body Snatchers basically gives the game away. But the film is so masterfully constructed, so deeply considered, that it is spellbinding even when one knows the inevitable narrative conclusion. In Hausner’s droll version of the oft-told story, scientists Alice (Emily Beecham) and Chris (Ben Whislaw) have developed a new kind of flower, one that demands laborious attention but rewards it’s keeper with feelings of happiness. Beecham takes one home to her son Joe, and soon he’s acting differently. Eventually, everyone in the lab is acting strangely and Beecham is left wondering if she is going insane or if this plant is actually changing the people around her. Hausner has a dry sense of humor, and it’s to the film’s credit that any character changes are only subtly pitched after their potential infection at the hands of this genetically-engineered botanical monstrosity. It’s a matter of degrees, a dead-eyed look or a lingering smile or a too-friendly ‘hello,’ that gives everything a slightly ‘off’ feeling. Hausner has a detached, almost clinical visual style. The camera is constantly panning left or right in slow, metronomic rhythm, or will very gradually push in to isolate something or someone. Hausner frequently uses windows and glass panes to visually separate characters within the frame, creating a profound sense of solitude. Some critics have suggested Little Joe is a kind of metaphorical indictment of antidepressants, but the film resists any straightforward, literal reading. Certainly there’s something here about the nature of parenting, losing oneself totally in the care and tending of someone or some thing. But Little Joe feels to be getting at something even larger, and perhaps even more ineffable than that. It’s a profoundly 21st Century film, replete with sinister corporations, science run amok, lax regulations, dismissal of mental health concerns, and the desire to control and organize nature to our own liking. In the old symbolic battle between the garden and the wilderness, Hausner has weaponized the garden. Daniel Gorman

Saint Maud

It doesn’t take much to surmise why indie studio-of-the-moment A24 snapped up Rose Glass‘s creepy debut Saint Maud right out of the Toronto Film Festival. Pulsating as it is, this psychological horror is a masterclass in slow-brewing tension that sees nurse Maud (Morfydd Clark) enter the home of dying ex-dancing star Amanda (Jennifer Ehle) in order to take care of her in her final days. The result is an initial tentative friendship between the two that becomes increasingly volatile when Maud’s newfound devotion to orthodox Christianity clashes with the former artist’s wilder side. Glass smartly opts for the slow accumulation of horror, impressively orchestrating the unravelling mood of Maud’s repressed self-involvement. This allows the film’s incredible sound design to take center stage, as every diegetic action contributes another layer, while Welsh newcomer Clark proves a dark revelation in her eerie maintenance of Maud’s altruistic facade. The bodyshock techniques and supernatural elements of Saint Maud recall the distortion between reality and delusion in Darren Aronofsky’s “Black Swan” (2010), which also focused on the obsession of an ambitious woman fervent on what her destiny should be. If anything, one wonders perhaps too much about Maud’s past, and Glass does not seem keen to provide much of an outlet for her beyond a tenuous friend who reveals very little in the way of backstory. There is a palpable feeling of something sadder and more unrelenting underneath Maud’s existential dilemma, psychological territory that feels prepped but ultimately isn’t mined. But what is present still makes for much chew on, particularly concerning religion and the problematic nature of prioritizing sacrifice over personal fulfillment. So while Saint Maud may well prove tough viewing for people with traditional ideas about faith, their conversion was never likely the aim of this tense, challenging exercise in subversive thematics and dogmatics. Calum Reed

Don’t Look Down

The scene is set. By arrangement, five wronged strangers convene for dinner at a high-rise apartment in Paris, all with an axe to grind against the man they loved. Each person takes it in turn to confront him off-camera, and although the group spends the entire length of the runtime talking about this man, we never actually see him or hear mention of his name. It’s a gutsy premise for French directors and real-life couple Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau, stalwarts of French queer cinema; here, they must rely on the budding rapport, between victims of emotional abuse, to build appeal and intrigue in what is essentially an askewed chamber piece. For the most part, Don’t Look Down succeeds in that regard; while less thoughtful than compatriot Patrice Chéreau’s similarly elegiac work Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train, which is a cinematic milestone in queer catharsis, this film is at least as refreshingly frank about sexuality, as the subjects perversely choose to relate to each other through their sexual exploits and fantasies. A claustrophobic, erotically-charged experience, Don’t Look Down is laden with the sort of psychedelic cinematography of a Nicholas Winding Refn picture, aptly capturing the mood of vengeful, broken exes, the most captivating of which is debutante actress Manika Auxire. Whether that translates to the kind of emotional punch Ducastel and Martineau want from their sorrowful finale is another matter, as not all of the characters emerge as sympathetic people — allowing some of them to give voice to their insecurities can occasionally feel more like an invitation for wallowing than any deepening of character. And yet, Don’t Look Down remains a unique vision, and benefits deeply from its eerie evocation of the damage relationships can do. Calum Reed

Deerskin

The life of a sociopath is laid bare in Quentin Dupieux’s macabre satire Deerskin, in which Academy Award Winner Jean Dujardin plays Georges, a man who spends his life savings on a second-hand deerskin jacket, only to then become unnervingly obsessed with it. Armed with such a bonkers premise, its director and star both commit to rendering Georges thoroughly devoid of any etiquette or feeling, absorbed only in his own status and the impression he makes on others. Dujardin is clearly having fun in a role that encourages his gift for comedy, while Dupieux gives the audience plenty of room for thought. Is Georges’ behavior a result of a mid-life crisis, the recent breakdown of his marriage, or simply a lifelong instinct for self-involvement? Dupieux poses interesting questions, but is considerably less generous with Georges’ companion of sorts, Denise (Adele Haenel), as the film fails to convey just why she is so invested in him. Her perceived gullibility is explained away rather flippantly, and her actions throughout feel more like a plot convenience than any natural extension of her character. The duo’s propulsion into the world of filmmaking represents a rather tongue-in-cheek nod to the perceived narcissism inherent in the profession; and while there are a couple of amusing movie-related jokes, the humor largely remains deliciously morbid, ratcheting up the Georges’ lack of control to amplify the suggested danger in his actions. But there is always a clear narrative trajectory, and, unfortunately, Dupieux does not seem to be able to surprise beyond the outlandishness of his comedy, the eventual descent into psychological horror territory ultimately feeling schematic. Deerskin is still wicked fun and earns some goodwill for its sheer originality, but its successes remain decidedly minor and ultimately won’t live in the memory for long. Calum Reed

By the Grace of God

Francois Ozon‘s latest jumps from the testimony of one character to the next, following the thread of its main subject: a priest’s sexual abuse of children over the course of many years. But at some point in the midst of developing an investment in each of these on screen individual’s personal accounts, more thorny sub-themes enter into the film. By the Grace of God is a narrative film constructed around the real life case of the sexual abuses committed by a French catholic priest, Bernard Preynat. The focus is less it’s true crime hook, though, than it is the way an organization is built-up by the victims of these abuses, as a means to try and raise awareness of the institutionalized crisis at the heart of the Catholic Church. The film doesn’t visualize the accounts of these individuals, but it’s still tough to watch the characters just talk about what they’ve been though, and how it has affected their lives. Particularly powerful is the testimony of Emmanuel (Swann Arlaud), who gradually comes to a realization that the abuse he was subjected to might be the reason that his life is such a wreck, but that it’s also given him a purpose and a goal in life: to raise awareness. Ozon’s approach is stylistically flat and overall a bit rushed, since this story was still developing even as the film was being made. But By the Grace of God is still compelling for the way it speaks to the realities and ramifications of pedophilia in the Catholic Church. Jaime Grijalba Gomez