In 1954, a 19-year-old girl named Sylvette David sauntered past Pablo Picasso’s window. The aging artist was instantly beguiled. A few weeks later, he revealed a portrait of David, the first of 60 that he would paint that spring. She became his inspiration, his Girl with the Ponytail, his muse. The muse is one of western culture’s enduring archetypes: Elizabeth Siddal, the pale goddess who appeared in the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti; Lou Andreas-Salomé, desired by Freud and Riilke and Nietzche; Alice Liddell, cherubic and innocent, immortalized by Lewis Carroll’s fantastical stories of Wonderland. The word “muse” derives from the Proto language root men, which means “to put in mind.” According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Osiris originally had nine muses, the Sylphlike daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, and with these alluring young women he traversed Europe, enlightening villagers and spreading artistic elucidation.

The Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang has, for three decades, found inspiration not in a beautiful woman, but in a sad-faced man he found living on the streets of Taipei 30 years ago. Tsai met Lee Kang-sheng (whom Tsai described as a delinquent) when the filmmaker was working in television. Tsai, who was born in Malaysia and moved to Taiwan in his 20s, became fascinated with Lee’s “air of mystery, ennui, brooding silence, and slowness.” Tsai vowed to never make a film without Lee. “Because of Lee Kang-Sheng, I became more flexible,” Tsai later said. “I shouldn’t insist on this or that. It should depend on individual actors. How should I bring out the most natural from each? That became something very important to me… On the second level, in the beginning, I didn’t intend to film Lee Kang-Sheng in every film. It was perhaps fate that pulled us together.” Elsewhere, Tsai said, “In my eyes, Lee Kang-sheng is the world’s most anarchistic person. His whole essence goes against all the standards set by society, especially those of the acting profession, and against preexisting notions of performance.”

In Tsai’s feature theatrical debut, Rebels of the Neon God, Lee plays Hsiao-kang (the name given to almost all of Lee’s characters), a lonely, disillusioned drop-out who seeks solace from his menial quotidian existence in the flickering lambence of the arcades. Like so many of Tsai’s characters, Hsiao lives a penurious life in a sordid, ramshackle building in a less-than-lovely vicinage of Taipei. Things only get worse for Lee’s woebegone wanderers — a despondent salesman in Vive L’Amour; an alienated tenant living in a dilapidated building who finds himself entranced by his beautiful neighbor in The Hole; a projectionist in an old, moribund movie theater in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (a film that Tsai put on his own Sight & Sound top-ten in 2012); a lovesick street vendor who hocks watches in What Time Is It There? before becoming a watermelon-slurping porn star in The Wayward Cloud.

Lee, who has never seemed very interested in typical thespian technique, creates an indelible anti-character; with consummate somatic control and not a trace of ego, he exudes an air of sagaciousness, a sense of the impossible realized.

In 2013, Tsai released Stray Dogs, which he claimed would be his last film. Lee is a crestfallen father who spends his days holding cardboard signs on the side of the street while his children stare with unutterable longing at groceries in the store. The film, Tsai’s first digital feature, represents the peroration of the character around which all of Tsai’s previous films had revolved. Lee’s unnamed father returns home and finds a single raw cabbage, which the children have adorned with lipstick and dress. He gazes at the vegetable, then kisses it, then devours it. It is a scene of abandoned dignity, pitiful, the behavior of a man who can no longer pretend in front of his children that he isn’t destitute. The film ends with a pair of static shots held far past the point of comfort, shots that remain unwavering, unrevealing, for almost half an hour. We watch Lee and a woman stare at something, but instead of seeing what they see, we see them, watch their minute movements. Lee fidgets, drinks from a glass bottle, his gaze drifting from the woman to just out of frame as he contemplates something while the woman’s unflinching eyes gleam with tears. Finally, after ten minutes of wordless rumination, he makes his move, putting his hands on her shoulders, resting his head on her. Tsai cuts to a reverse shot and we see what has captivated them: a mural (made by Jun-Honn Kao) depicting a sea and rocky shoreline. They continue to gaze at this hidden work of art. Then, she leaves, taking the flashlight with her, leaving him alone in the dark. After a few long, lonely moments, he leaves too.

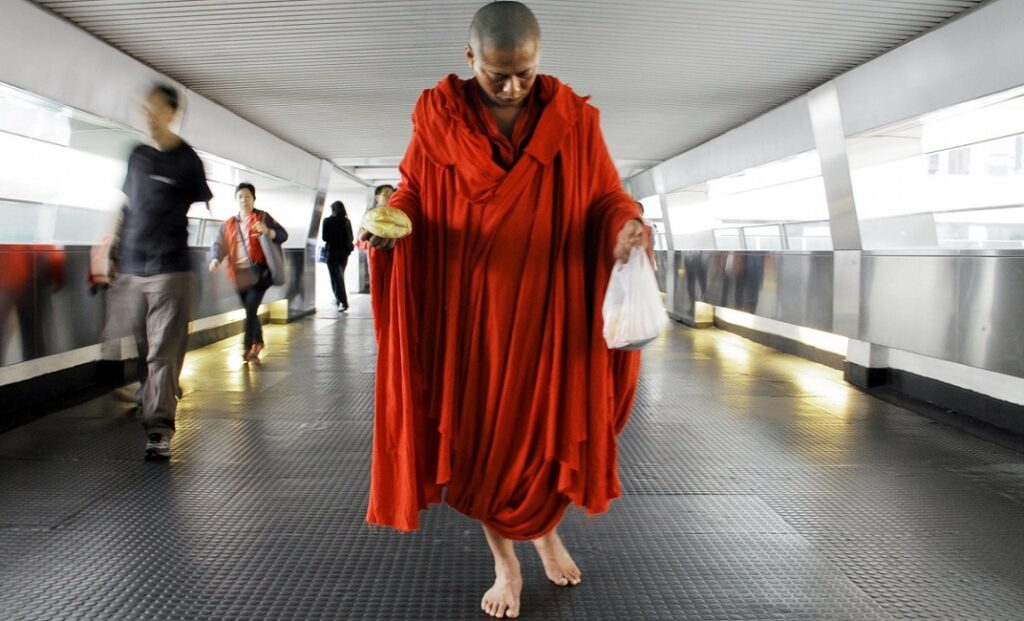

After Stray Dogs, Tsai began to eschew anything resembling conventional character and plot with his series of experimental shorts about the Walker, a monk (inspired by Xuanzang) garbed in a red robe, who moves with extreme languor through various locales. He appears almost stationary, less a person than a decoration, this strange sight surrounded by scenes of bustling modernity. Lee, who has never seemed very interested in typical thespian technique, creates an indelible anti-character; with consummate somatic control and not a trace of ego, he exudes an air of sagaciousness, a sense of the impossible realized.

The Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang has, for three decades, found inspiration not in a beautiful woman, but in a sad-faced man he found living on the streets of Taipei 30 years ago.

“[Lee] has collaborated with some other filmmakers,” Tsai told Film Comment in 2015. “However, I think most of them don’t know how to use him. I mean, Lee is a very special person.” In Days, Tsai’s first proper feature in seven years, the now-middle-aged actor sheds the monk’s robe and returns to the humdrum mundanity of daily life. Scenes comprise a single, impeccably composed shot that can go on for ten minutes or longer. Some may be tempted to say that “nothing happens,” but that would ignore the mesmeric way Tsai reveals his characters’ unspoken inner lives using images instead of words. There’s something comforting about the film, its familiar torpor and all those prolonged moments of loneliness. The opening shot, of Lee gazing out the window as it rains, harks to several of the director’s recurring themes: there’s the presence of water, and Lee’s character suffers from neck pain, an ailment that first appeared in The River. All of Tsai’s films are in some way concerned with the act of looking — at arcade screens, at secret murals, in darkened movie theaters, and out windows on rainy afternoons.

And, of course, there’s the inveterate sense of loneliness from which all of Lee’s characters suffer. Here, his house may not be as ramshackle as before, and his body is beginning to show the detrition of age, but the ache of longing remains. What makes Days different from Tsai’s earlier efforts is that it offers its lovesick loners the possibility of hope. Consider the incestuous ending to The River, or the cruel act of oral sex with which The Wayward Cloud leaves its viewers. (Tsai, who is gay but rarely discusses his romantic life in interviews, once said that modern sex seems “rarely joyful” to him.) Days doesn’t share the cynicism of those films. It offers its lonely hearts the chance to feel okay, suggesting that even if loneliness seems ineradicable, you can still find peace in beautiful moments. It suggests that all is not hopeless.

Over the next two weeks, our writers will review all of the feature films that Tsai Ming-liang has made to date, as well as a number of his prominent telefilms and short films. That makes for a total of 25 reviews (including a double review in one instance, a micro-review in another), which have been divided up into five sections representing very loosely defined periods in the director’s career: Pt. 1: Boys and Gods (1989-1992), Pt. 2: Love Like a River (1994-2002), Pt 3: Sleeping Sickness (2003-2008), Pt 4: Facing the Elements (2009-2015), and Pt. 5: Days Gone By (2015-2020).

Pt. 1: Boys and Gods (1989 – 1992): All the Corners of the World (1989), Li Hsiang’s Love Line (1990), Give Me a Home (1991), Boys (1991), and Rebels of the Neon God (1992).

Pt. 2: Love Like a River (1994 – 2002): Vive L’Amour (1994), The River (1997), The Hole (1998), What Time Is It There? (2001) / The Skywalk is Gone (2002).

Pt. 3: Sleeping Sickness (2003 – 2008): Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), My Stinking Kid (2004), The Wayward Cloud (2005), I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (2006), and Sleeping on Dark Waters (2008).

Pt. 4: Facing the Elements (2009 – 2015): Madame Butterfly (2009), Face (2009), The Walker Series’ shorts (2012-2015), Stray Dogs (2013), and Journey to the West (2014).

Pt. 5: Days Gone By (2015 – 2020): Afternoon (2015), Your Face (2018)*, Sand (2018)*, Light (2019)*, and Days (2020)*.

* Pending release in the U.S.

Comments are closed.