Alone

John Hyams’ new film Alone is a minor miracle. A terrifically tense thriller pared down to the barest essentials, it is survival horror in the best, most literal sense, following an intrepid woman who tries to escape her homicidal captor, locking us into the victim’s point of view, and becoming a kind of physical, experiential procedural. Hyams made his name with 2012’s Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning, a blast of cinematic maximalism that fused brutal, bone-crunching action with a heady stew of narrative and formal tricks cribbed from Gaspar Noé, David Lynch, and Phillipe Grandrieux. He spent the rest of the decade mostly spearheading low budget zombie fare for television, experience that has clearly informed his return to genre filmmaking. For Hyams’ Black Summer series, a Netflix acquisition spun off from the larger-scale Z Nation program that ran for five seasons on SyFy, he and his co-directors used long takes and oners less to show off than to save time, using exhaustive rehearsals as a way to reduce the number of setups required on their tight shooting schedule. This economy of means carries over to Alone, infusing the film with an almost primal simplicity. Constructed as a series of individual set pieces, each clearly delineated with a title card, the film eschews psychology and limits exposition to a couple of brief phone calls. Jessica (Jules Willcox) has packed up a U-Haul and is moving north, fleeing some unknown familial trauma. While on the road, she catches the attention of an unnamed man (Marc Menchaca) who is, to put it mildly, creepy. It’s a scenario familiar to many women: an outwardly friendly man, overly polite but also pushy and insistent, tries too hard to force a conversation and refuses to take a hint to back off. His true purpose is quickly revealed when he kidnaps Jessica and locks her in a basement. She manages to escape, and the chase is on.

Apart from a kindly stranger who makes the mistake of trying to help Jessica, Alone is a two-hander, and Willcox is phenomenal in what must have been an emotionally and physically grueling production. She runs through dense forest barefooted, braves rocky terrain and river rapids, is submerged in mud and water, all while constantly mustering hitherto unknown reserves of perseverance. Hyams films things mostly as a series of master shots, allowing actions to play out slowly before cutting to closeups. The result is an effective slow-fast-slow rhythm, a fascinating illustration of how a horror set piece resembles an action scene, just with a different tempo. There are almost no cheap jump scares here, with Hyams instead showing things in the deep background, like headlights on a car or a blurry figure, and watching as they get steadily closer and closer. These choices create a sense of creeping dread, forcing Jessica (and the viewer) to live in the moment as something beyond our control transpires in real time. Through canny blocking and framing, Hyams manipulates perspective to create claustrophobic, almost clinical enclosures. Even the relatively benign forest location takes on a patina of horrific possibilities. Tense and suspenseful, Alone is a stunning film, triumphant in a way that only few genre films can manage. Its catharsis is hard-won and well-earned. Daniel Gorman

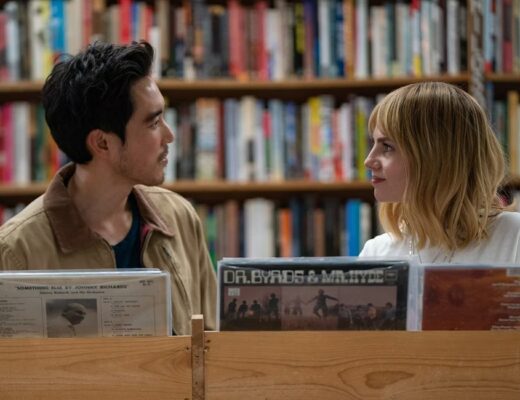

Dinner in America

Adam Rehmeier’s sophomore film Dinner in America updates an early-2000s brand of suburban misfit ennui with a winning, occasionally uneven blend of sweet and sour teen angst. It lacks the cringey earnestness of Napoleon Dynamite or Ghost World’s undercurrent of resigned melancholy, content to let its unconventional characters follow a fairly well-trod formula. Its two leads, deeply sheltered Patty (Tony-nominated Emily Skeggs) and vitriolic Simon (Kyle Gallner, sporting a squirrely undercut-mullet combo), form an unlikely bond predicated on a shared love for punk music. Patty is implied to have some sort of unspecified developmental disability, or to at least fall somewhere on the spectrum; at age twenty, she carries herself with the demeanor, and colorful, baggy wardrobe, of a pouty tween. Meanwhile, Simon is all too willing to hurl insults and pick fights, mostly with middle-age couples who have the misfortune to sit near him in restaurants.

To his credit, Rehmeier, who also wrote and edited the film, doesn’t let Patty fall into Manic Pixie Dream Girl mode, even as he upends expectations about crust punk Simon’s family background. When the two meet, she’s been unceremoniously fired from her job at a pet store and he’s wanted by the police for setting a house on fire in the first of many dinner scenes. Before long, she’s professing her biggest secret — sending love letters and x-rated polaroids to the ski-masked lead singer of her favorite punk band — and Simon has to decide whether to reveal himself as the anonymous John Q. Public. It’s both adorable and contrived, like something dreamed up by a teenage girl in math class, and Gellner nails Simon’s expression of horror and disgust when it dawns on him that this awkward, ungainly dope is his biggest fan.

Skeggs and Gellner carry the film with a relentlessly flickering energy, buoyed by John Swihart’s thumping, jittery score, which has the same comedic timing as the script. Every nuclear family we encounter — no divorces here — reads like a hideous caricature of suburban America, Norman Rockwell splattered with Pollock. Against this backdrop, Patty’s syrupy naiveté manages to soften Simon’s snarl, while his caustic charisma emboldens Patty to finally stand up for herself against a litany of generic bullies. There’s nothing groundbreaking at work here, but just like the impromptu song Patty and Simon record together, Dinner in America proves to be simple, goofy, and unexpectedly sweet. Selina Lee

Detention

John Hsu’s debut feature Detention isn’t so much a horror film with political undertones as it is a historical, political drama with brief flashes of horror imagery. Unfortunately, it fails to station itself effectively in either of its ostensible genre territories. Set in Taiwan during the 1960s, at the height of fascistic martial law, the film’s present-tense plot begins with two high school students waking up to find themselves trapped in their vacated campus. Flashbacks reveal that the protagonist Fang Ray-Shin (Gingle Wang) acted as a whistleblower against a secret leftist book club she attended, leading to the government-mandated torture and execution of several peers and teachers. Much of the film focuses on this past timeline, which also tells of a star-crossed love affair between Fang and her teacher Chang Ming-Hui (Meng-Po Fu). Through sophisticated framing, lighting, and production details, Hsu demonstrates a commendable visual aptitude, which is clearest when the film unfolds in the present tense. However, the knotted story places much of its emphasis on flashbacks, which become mired in tiresomely didactic dramatic conventions.

Also unfortunate is the film’s engagement with horror imagery: rather than capitalize on the genre’s potential for allegory or symbolic heft, Detention crudely grafts its horror iconography directly onto its story and offers very little beyond literalized expressions of already-present threats. The film’s spectral figures (beautifully animated, cadaverous, uniformed government officials) are simply stand-ins for known evils from the flashback timeline: fascist surveillance in the White Terror era of martial law. When it comes to horror, the film shows its hand too early and too carelessly. Its spooky moments are mostly compelling, especially in the first act, but the genre elements quickly feel weightless and out of place, deflated of allegorical potential. When it comes to political drama, the narrative is broad and manipulative, resulting in a rather standard, unsubtle historical piece with arbitrary and unsatisfying invocations of the supernatural. Director Hsu shows great potential, especially for a first-time filmmaker, and the film includes some striking images, but its cumulative effect leaves much to be desired. Mike Thorn

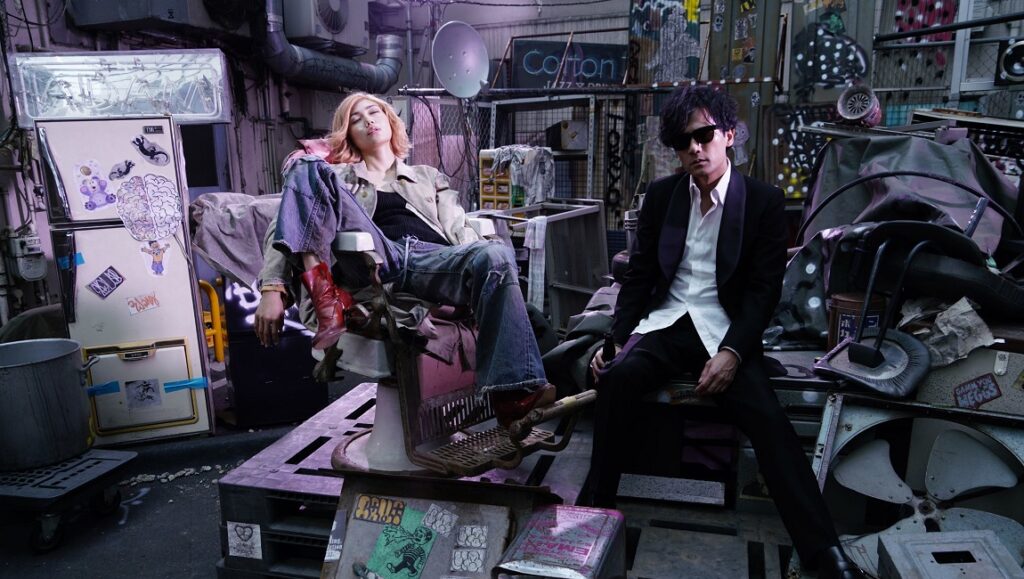

Tezuka’s Barbara

Manga and anime artist Osamu Tezuka has been almost universally praised for his works in numerous genres (romance, sci-fi, even erotica); his son, Macoto Tezuka, is a visual artist and filmmaker in his own right, but a more obscure one. Only recently, through the re-release of 1985 cult hit The Legend of the Stardust Brothers has Macoto started to earn broader attention, both as a unique visual artist and a storyteller. And now comes his latest, which has a tight connection to his father’s legacy in that it’s a film adaptation of one of his more adult-oriented works. Osamu Tezuka’s Barbara is a two-volume manga released between 1974 and 1975, and filled with art that bears the master’s endearing and unique stamp; the sketch-like style reflects the psyche of the protagonist, a writer tortured by his sexual fetishes and frustrations, whose problems are only exacerbated when he meets the eponymous Barbara and is launched into a world of witches, cults, mannequins and intense, surreal imagery.

This film version of Tezuka’s Barbara promisingly opens with some images and quotes from the manga, and follows most of its plot elements. But the manga was elevated partly by the way its stories offered a great variety, and also through the acute understanding of how each shaped the development of the protagonist. Macoto opts for a more traditional and linear exploration of the relationship between his two principles, casting Baraba as a typical muse. Admittedly, room is made for the wilder stuff from the elder Tezuka’s work, including decapitations, bestiality, and a black mass. But even with these sequences, which indeed are comparable to the creative instincts and frenetic energy of the original work, the film suffers by trading in the surrealist, oneiric tone of the text for one far more ambiguously defined — more Nolan than Lynch. In truth, this Barbara’s greatest chance for success probably lies with an audience unfamiliar with the manga, who can focus more on the film’s individual strengths — like the multifaceted lead performance from Sion Sono regular Fumi Nikaido, who here manages to move from the comic to the profound in the space of a single scene. With more of a willingness to pursue the extreme and the weird corners of this story, without fear of alienating a new audience, Barbara could have been a special tribute. Instead, it’s strangely tame for a director of Macoto’s background. Jaime Grijalba Gomez

The Mortuary Collection

Ryan Spindell’s The Mortuary Collection is an absolute blast, a delightfully gory and darkly comic throwback to old horror anthology films. While stuff like the VHS and ABCs of Death franchises imposed a fairly strict format upon a wide range of creators, Spindell writes and directs all of the segments in this collection himself, allowing for a more consistent experience than one usually gets with these kinds of portmanteau films. Spindell has even got his own version of the Crypt Keeper on hand, the incomparable Clancy Brown, acting as emcee for the proceedings. Brown is Montgomery Dark, first introduced under layers of skeletal old man makeup and presiding over the funeral of a child in his growly baritone (and relishing it perhaps a bit too much). When a young lady named Sam (Caitlin Custer) comes inquiring about a job posting at the funeral home, Dark regales her with tales of all the dead folk who have passed through his doors. Dark’s first story is the shortest — essentially a brief gag that sets the tone for what’s to follow, as a woman pickpocketing unsuspecting men at a party decides to open the wrong locked cabinet. The second involves a manipulative college student who lies to a one-night stand about wearing a condom and gets a particularly grisly comeuppance. The third follows a put-upon man who’s tired of caring for his invalid wife. When he decides to rid himself of his burden things do not go as expected. The fourth is the longest, a cheeky homage to Carpenter’s Halloween that happens to feature the same young lady who is interviewing with Mr. Dark. It’s got the most obvious twist of the bunch, but, like the other stories, it’s willing to go to a particularly dark place to make its point.

Spindell is working through a number of influences here, most obviously EC Comics and Tales From the Crypt, but also early Tim Burton and Sam Raimi, Fred Dekker, and a healthy dollop of ’80s slashers. He’s got a finely tuned sense of the gothic and expressionistic; the production design throughout is ravishingly beautiful, with deep, dark colors, elaborate patterning, and a lavish attention to detail. It all feels very out of time, with Spindell mixing and matching eras and modes with gleeful abandon. It’s mostly affectionate, although Spindell occasionally tries to put a lampshade on the whole endeavor by having Sam remark upon the history of these kinds of omnibus films with ironic snark. It’s about the only bum note in an otherwise wonderfully realized bit of funhouse horror, though Spindell ultimately repudiates this ironic touch with the film’s final swerve. All in all, there’s an appealing sincerity here, an endearing devotion to the genre and its tropes that leaves a lasting, easy smile. Daniel Gorman