Lahi, Hayop

Lav Diaz knows violence. The director’s filmography is virtually an exemplar of the temporal nexus of historical and contemporaneous representations of authoritarian exploitation. Lahi, Hayop holds that line, focusing on a string of snowballing murders and intimidations. But the film also appears to find Diaz coming to loggerheads with his own ideas, and contesting history through quasi-scientific projection. Central to the film is the legacy of land, and the horrors of its colonial pasts — in particular, the commodity fetishism of illegal smuggling routes carved out through the Philippines. This history threads contemporary conceptions of greed through the focal depiction of present-day migrant workers, whose vexations over minimum wage labor manifests as fits of (otherwise) inexplicable rage. Violence between these members of the working class is presented in an immediate, bracing way, but it also suggests the spectres of the historical figures who haunt the environments in which Diaz chooses to shoot.

Unfortunately, this meaning is undercut by a voice-over that means to frame said violence instead as the result of ‘undeveloped cerebral activity.’ It’s even suggested that those with truly evolved perspectives are those of religious icons: the saints, the Buddha, Jesus Christ. Imposing this idea on the film is conforming to religious utopianism, the malleable figures of history idealized and placed within a trajectory of evolution as the aspirational result of a reconfigured psychology. And it’s reductive in the face of a history that’s plainly shown us the material conditions which breed violence. As biological factors and ‘animalism’ become Diaz’s primary lenses, it’s hard to see where the political has its place, how it isn’t immaterialized through utopianism. Hence the contradiction here: Diaz’s signature long-takes articulate the way people are made the product of their environment, but that affect emphasizes biological factors that turn the film more fatalistic than political. Diaz seems to suggest that further evolution is needed in order to conquer our most corruptive emotional dimensions, casting the icons of religion as aspirational in value. In the process, he deprives his human subjects of agency, and ultimately sees time as the only balm. Zachary Goldkind

Tragic Jungle

Yulene Olaizola’s elemental fifth feature, Tragic Jungle, is a willfully beguiling work. Set in the 1920s, in the inhospitable heart of a jungle bordering a river between Mexico and what is now Belize, the film follows three of the wildland’s wandering genera: a group of sex-starved Mexican chicleros, a mysterious Belizean virgin they encounter, and an English colonialist governor hell-bent on securing her extermination. The film’s ominous narration cautions against any mythical vainglory one might seek in comprehending, even conquering this place: “Unfortunate you, if you cannot understand the mysteries of the jungle. […] The jungle gives you plenty, but also takes from you.” It’s a shame, then, that Tragic Jungle is equally unfortunate in its reliance on an atmosphere of feverish malaise and other tropes of the tropics. With neither a sensible narrative trajectory, nor a convincing stylistic justification, Olaizola instead elucidates a rote and second-rate reading intertwining the violence of patriarchal and colonial systems with an indigenous myth that may only draw tangential references to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, and little more.

This myth is of Xtabay, a demon seductress who preys on man’s animalistic instincts and lures them to unknown deaths. Agnes, the aforementioned virgin, might be Xtabay, or at least her metaphorical stand-in. The chicleros who find her unconscious first demand information concerning their rival Englishmen’s whereabouts, then use her as bait, and finally — one by one — succumb to her wordless seduction; their leader initially warns against fraternising with the probable enemy, but is himself one of the first to give in. Most of Tragic Jungle follows the men from one clearing to another, deliberating whether to renegade from their contract with an unseen boss and instead cross over to smuggling rubber gum. This stultifying narrative mode is bookended by an opening goose chase enacted by the English governor, in which Agnes, her companion, and their guide are shot down and seemingly killed, and a similarly bloody shootout between the governor and the chicleros towards the end. There is otherwise little clarity regarding the function of Xtabay’s manifestation as Agnes, and no explanation as to whether she is hunted for this or some other transgression; in a stronger film, such opacity would have an elaborate and structurally complex mythos to match. “Here, everything is of the same colour”; Aguirre, raving-mad, might have said the same. Olaizola’s earnest metaphor for exploitation, on the other hand, reinforces this observation a little too well. Morris Yang

Padrenostro

The best thing one can say for Claudio Noce‘s Padrenostro is that its narrative is well-intentioned. The film attempts to reckon with the lingering effects of an assassination attempt on Italy’s deputy police commissioner (inspired by Noce’s real-life father, who was almost killed in 1976) on both a personal and collective level, as the emotional fallout from the attack ripples across generations and extends outside of their immediate nuclear family. But good motives mean nothing unless they’re actually followed through on, because otherwise you just have an empty gesture, which is a far more fitting title to bestow upon Padrenostro.

Bearing witness to this inciting incident is 10-year-old Valerio, who after seeing his father nearly murdered in front of him, begins to fear for his family’s safety and becomes hysterical. At dinner, he imagines that the visiting guests will open fire once they’re let in through the front door. More importantly, the event forces Valerio to learn a lesson most only receive during their second decade on this planet: that his father, Alfonso (Pierfrancesco Favino) isn’t invincible, and so the threat of his being killed at any moment hangs over their ensuing, awkward interactions. It’s at this point that Valerio meets Christian, a slightly older boy who takes the young man under his wing; soon, he begins to appear whenever it seems like Valerio needs his father most, serving a surrogate paternal figure and a possible figment of Valerio’s imagination. Thankfully, Noce doesn’t commit to the most obvious of narrative dead ends, but he side-steps that one for a pretty hackneyed turn all the same: that Christian’s father was the one who tried to kill Alfonso at the start, turning what should be Noce’s examination of a slice of his rather specific and very much “real” trauma into a contrived thriller that exploits and trivializes the severity of these events.

By the end, it’s not even firmly established just what the emotional relationship between Valerio and his father entails at this point. Rather than investigate the neo-liberal institutions and policies that made men like Alfonso and Christian’s father supposed “enemies” in the first place, Noce instead chooses to end on a framing device that begs for platitudes of understanding and acceptance. As per usual with “well-intentioned” art like this, the type that Obama-loving critics just eat up, this is best-suited for the nearest dumpster rather than the next international film festival. Paul Attard

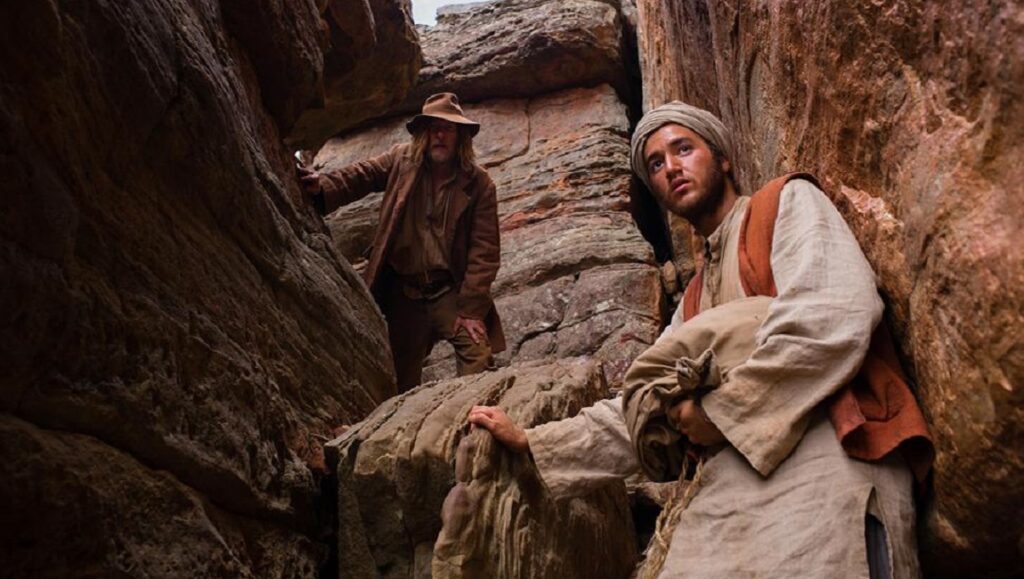

The Furnace

The new Australian western The Furnace opens with text explaining that, in the 19th century, the British government imported camels into the Outback, as they were one of the few animals able to both navigate and withstand the region’s harsh terrain. Oftentimes, their Afghan, Persian, and Indian handlers were forced into indentured servitude, unwittingly becoming slaves to the Monarch. They were seen not only as unwelcome guests, but also a dangerous threat due to their connection to England, the color of their skin, and their religious beliefs. It is perhaps for these reasons that the Aboriginal tribes of Australia often took pity on these men, feeling a kinship with these “outsiders,” and allowing them to become part of their way of life. The Furnace follows one such man, Hanif (Ahmed Malek), shipped from Afghanistan by a father who saw him as nothing more than a disappointment. After the death of his friend at the hands of a white man — and his insistence on helping a bullet-ridden gold thief, Mal (David Wenham, The Lord of the Rings) — Hanif is shunned from the Aboriginal tribe he once called family. From there, the story unfolds as most Westerns do, with Hanif and Mal on the run from both the law and a shady man from Mal’s past referred to only as “The Devil.” The symbolism is not subtle.

Granted, looking for subtlety in most Westerns is like digging for gold in a diamond mine. Here making his feature-length debut, writer-director Roderick MacKay ticks off all the genre’s requisite thematic checkboxes: morality, loss of faith, the true price of greed, vengeance, redemption. It soon becomes clear, though, that what we are witnessing is not just your basic Western yarn but also Hanif’s very own walkabout, his personal journey to discover both who he is as a man and his place in the world. It is a somewhat clever twist on a story that’s been told time and again, and a welcome one, as MacKay isn’t offering much depth when it comes to the horrors of British Imperialism, which feels at most like window dressing. A subplot involving a British general (Jay Ryan) and his fractured relationship with his son feels especially superfluous, existing only for Hanif to come to a personal realization that frankly did not need such story acrobatics. Lacking the brutality — and, frankly, the ambition — of recent Outback westerns such as The Proposition and The Nightingale, The Furnace feels almost quaint: It’s an involving, gorgeously shot tale that provides entertainment and not much else. This admittedly may not have been MacKay’s true intent, but considering everything currently going on in the world, I’ll take small pleasures where I can find them. Steven Warner

The Return of Tragedy

Bertrand Mandico made quite a splash with his first feature-length film The Wild Boys in 2018, but he’s been making accomplished shorts for well over a decade. His latest, the 25-minute The Return of Tragedy is, in his own words, a “tribute to the New York underground cinema of the 80s.” Mandico clearly knows his film history: his movies, short and long, pay homage to Kenneth Anger, R.W. Fassbinder, Guy Maddin, the outsider art of Henry Darger, Jack Smith’s canonical Flaming Creatures, Christopher MacLaine’s The Man Who Invented Gold, and the poetic, esoteric Euro-smut of Walerian Borowczyk, amongst other avant-garde touchstones. Still, evoking the hardcore films of the ’80s post-No Wave scene by Nick Zedd, Richard Kern, and Lydia Lunch is a different vibe altogether, and Mandico doesn’t even begin to approach the genuinely dangerous, transgressive nature of those outré maniacs.

Then again, Mandico may not be trying to outdo his forebears: The Return of Tragedy plays more like a small-scale lark, the work of a bunch of friends fucking around over a long weekend. The loose, awkward staging resembles nothing so much as a porno, although Mandico scribbles all sorts of cryptic tomfoolery in the margins. Two cops break up a backyard meeting of some kind of cult, where an aged, near-unrecognizable David Patrick Kelly presides over some arcane ritual that sees Elina Löwensohn lying prone while her liver floats several feet above her, still attached to her body by a length of intestines. This is intercut with scenes of police interrogating Kelly and Löwensohn, and glimpses of a young woman roaming the streets, covered in sores and pustules (clearly made out of silly putty). Kelly is referred to repeatedly as “Kate Bush,” spouts gibberish about “the hypocrisy of teeth” and “the importance of pinched lips,” and declares that “a smile is not a peaceful act, it is a carnivorous statement.” Mandico is certainly not shy about painting the police as buffoonish. At one point the officers grow phallic mandibles on their noses, which they then furiously masturbate. Later, bystanders unfurl a “Fuck the police” banner and the soundtrack repeatedly intones “we don’t want to do anything to scare your children.” These cops are repeatedly stabbed and then reborn, the scenario repeating itself over and over in a kind of eternal return. Charged political statements notwithstanding, all this comes across as aesthetically playful: handmade special effects use lots of papier mâché and clearly visible strings, while the delicately grainy 16mm images have a soft, pastel feel. On the whole, The Return of Tragedy is perhaps a little too weird to fully explicate — there are orifices and wombs and anuses all over the place — but it’s a worthwhile experience all the same. Daniel Gorman