John and the Hole

Tapped by Cannes for its theoretical 2020 slate, John and the Hole carried a bit more intrigue than most films heading into Sundance ’21. This designation, regrettably, is mere red herring, as Pascual Sisto’s debut is but another in this millennium’s spate of creepy kid slow-burns, and also emptier than most. The straightforward premise involves the eponymous John (Charlie Shotwell), an awkward 13-year-old with a penchant for saying “okay” and who also, seemingly on a whim, decides to drug his parents (Jennifer Ehle, Michael C. Hall) and older sister (Taissa Farmiga) and deposit them into a half-made bunker he recently found in the woods. He brings them a little food and water, but mostly seems concerned with continuing his idle adolescence in their absence, playing video games and inviting over a friend for an extended weekend sleepover. His motivations remain unsettled across the film’s runtime, though all of these developments are prefaced by a conversation he has with his mother in which he asks, “What’s it like to be an adult?”

There doesn’t seem to be much more to it than that; the film would love you to read sociopathic tendencies into John, and so it litters the film with bits of oddity, such as when John and his friend repeatedly half-drown each other in an effort to encounter some vision, or the numerous, abrasive conversations the youngster has with adults who are clearly disconcerted by his weirdo demeanor. But these beats are just signifiers, the bow on an empty box. Instead, the film is a mostly blank slate, one which revels in John’s dark bid at Home Alone-type antics and fetishizes his flat affect, and which relies on ample audience projection to fill in the undeveloped gaps. It seems evident that Sisto and screenwriter Nicolás Giacobone are tilting toward Haneke, but the film’s shallow psychological probing does little to earn such grace. The kind of ambiguity the Austrian director embraces, which in his successful efforts is aided by a chilling austerity and often morphs into psychological expansiveness, is here traded for some half-cooked ideas about the insidious relationship between parents and their children. The film’s fairy tale-esque title hints at just such a fabulist wrinkle — as does a seemingly disconnected mother-daughter side plot that first frames and then occasionally interrupts John and the Hole and inverts the power dynamics of the narrative proper — but it too is much ado about nothing, a surreal flourish that mistakes mystery for depth.

The film more successfully establishes an appealing formal texture. Sisto and DP Paul Özgür frequently deliver captivating images, a go-to being a nighttime side-view of the family home, its façade almost entirely glass, the illuminated interior contrasting the shadowed geometric structure to create a dollhouse view of domesticity. Even the film’s more minimalist, less ostentatious images, such as a splash of blood-red leaves amidst the verdant forest foliage or interior, bottom-of-the-bunker shots that capture streaking water lines and imply its imposing verticality, don’t succumb to the same blandness as the narrative. Elsewhere, John and the Hole’s sound design is effective at establishing tone, particularly in early scenes set to metronomic rhythms — a tennis ball machine launching and the subsequent whoosh of the racket, the sputtering of a sprinkler, the bouncing of a ball off of a ceiling — all of which accentuates the forthcoming disruption of the everyday. Unfortunately, all this craftsmanship is in service of a film too confident in its moody but shallow vision. There’s a certain hubris required of films that revel in such pronounced ambiguity, one that transfers much of the responsibility off of the filmmaker and onto the viewer. In this regard, John and the Hole is effectively a bait-and-switch, promising its audience psychological acuity but offering only soft pop references.

Writer: Luke Gorham

Prisoners of the Ghostland

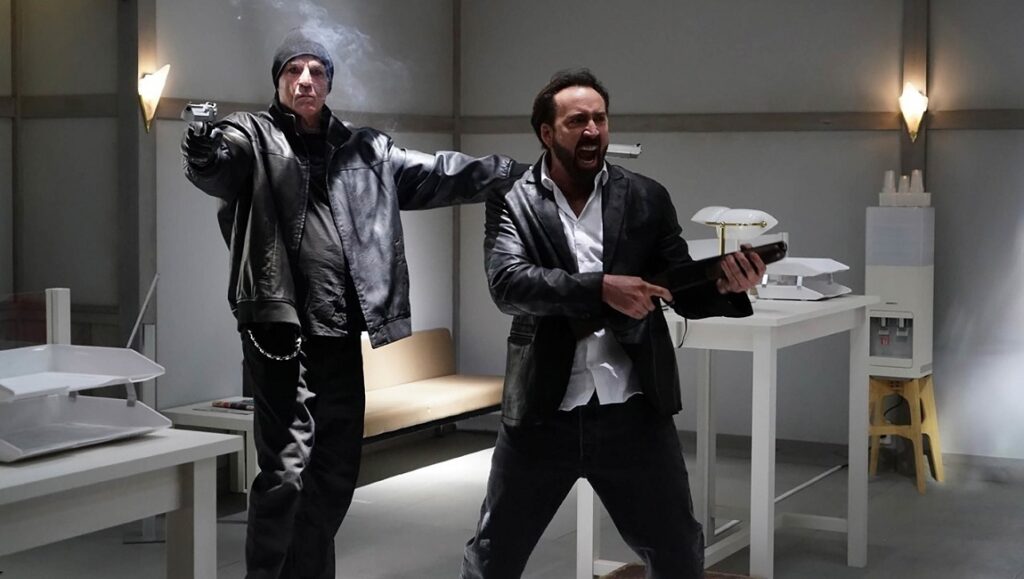

If there’s any director working today that understands what Nicolas Cage means when he describes his style as “nouveau shamanic,” it’s Sion Sono. Cage and Sono work through similar means, a highly-stylized and often wildly over-the-top expressivity, getting at the emotional truths that make their work so compelling. After all, Sono’s masterpiece, Love Exposure, is at its core a melodrama, albeit one replete with severed dicks, Female Prisoner Scorpion cosplay, and up-skirt photography performed like ninjutsu. Sono’s actors routinely perform like Cage, going well beyond the range of actorly realism to arrive at something more affecting and memorable. Prisoners of the Ghostland, the collaboration that had to happen, is sometimes lacking in the emotional rawness that characterizes each man’s best work, but it largely makes up for it with imaginative production design, memorable action spectacle, and gorgeous cinematography.

Originally conceived to shoot in America, Ghostland was delayed when Sono suffered a heart attack and, to save the film, production moved to Japan. To that end, the film’s style is that of East meets West writ large, with much of the film taking place in Samurai Town, an old western-styled town that sports as many cowboys, including Bill Moseley’s Governor, as it does samurai. The set for Samurai Town most clearly recalls Tokyo Tribe’s fantastical locations, and, like that film, most of what’s depicted on screen would seem more at home in an anime, where expressivity is valued over grounded verisimilitude. Sono casts Cage not as the tiresome meme, but as a symbol of American masculinity. If the mission that the Governor gives Cage’s hero sounds an awful lot like Escape from New York, well, Cage is Sono’s Kurt Russell, as well as a part of John Wayne’s macho lineage. Our hero must go to a place called the Ghostland to rescue the Governor’s granddaughter (Sofia Boutella, who doesn’t have a lot to do) from the clutches of radioactive mutant ghosts. Any false move and the suit Cage has been zipped into will trigger highly localized explosions. Act with violence towards a woman? Lose an arm. Feel even a little bit horny? Bust a nut.

When he arrives at Ghostland, Cage finds a city made of wooden platforms in the shadow of a nuclear power plant where time stands still. Some people here have been turned into mannequins — again, a detail here with a clear counterpart in Tokyo Tribe — and the look of them, and many of the village’s other eccentrics, is both unnerving and delightfully novel. Sure, this town beset by radioactive monsters clearly recalls The Road Warrior, but the feeling of the Ghostland is a distinctly Sono pop confection. Yet again, the director finds himself contending with the momentous event of his latter-day career: the 2011 earthquakes and subsequent nuclear disaster at Fukushima Daiichi. Films like Himizu, Tokyo Tribe, Love & Peace, and The Whispering Star are all preoccupied with the fallout of those events, and Ghostland is too. The plague besetting Ghostland is a nuclear one, and the ghosts themselves are a result of this terrible accident. In other words, even a film this superficially silly, in Sono’s hands, can’t help but be informed by the social anxieties and nuclear terrors that have so moved him in the past decade.

But as the film settles into its rhythms in the Ghostland, it also starts to drag with too little going on beyond a tour through production design. Sure, the unnamed hero has a few dreams that propel him forward — both narratively and toward his own redemption — and yes, this is all gearing up for a big finale, but an additional action sequence or two could have enlivened things in this middle going. Whatever else one might say of Sono’s films, they are rarely sedate, and so it’s surprising to watch one go this long without some bit of gonzo or kinetic excitement. When Prisoners of the Ghostland reaches its finale, however, it takes the form of a very worthwhile cowboys and samurai brawl that, while not among the best Sono action sequences, bears the director’s trademark energy and even has a few surprises up its sleeves. This is not either man’s best work, but it’s a good fix for those in need of one.

Writer: Chris Mello

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

There’s something bracing about encountering a genuine oddity like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, a truly hand-crafted bit of regional, DIY filmmaking that bends and breaks narrative rules to suit its own deeply unnerving agenda. Something of an offshoot of the burgeoning “desktop” horror flick (think Unfriended or the more recent Zoom horror of Host) We’re All Going to the World’s Fair isn’t limited to a laptop interface; instead, it freely mingles the ontological qualities of a variety of internet ephemera — loading screens, time/date stamps, creepypasta, YouTube, ASMR — alongside adolescent angst and the general unease of having reality mediated at all times by the internet. Directed, written, and edited by Jane Schoenbrun, the film details the agitated mental state of teenager Casey (newcomer Anna Cobb, delivering a remarkable performance) as she embarks on a game of “World’s Fair,” an online horror phenomenon that involves repeating an incantation and smearing a bit of blood across a computer monitor. Convinced that the game is real and that it is slowly changing her in unknown ways, which is what the surrounding urban legend and documentation from other players suggest, Casey begins recording herself at night and posting the videos to her YouTube channel. She’s eventually approached by JLB (Michael Rogers), an anonymous entity who tells her she is in danger and who seems to have special insight into her transformation.

Schoenbrun shoots large swathes of World’s Fair with the audience fixed in the place of Casey’s YouTube viewers, creating the disorienting effect of the film’s actual audience becoming a hypothetical fictional audience, all while Casey stares straight back at us. It’s a fascinating way to complicate modes of identification, while also implicating the audience in Casey’s gradual deterioration. JLB’s motivations are murky, and while we see his face, Casey doesn’t, only interacting with his online avatar. There’s an overwhelming sense of ennui at work throughout the film, as Schoenbrun and cinematographer Daniel Patrick Carbone embrace the chunky pixelation and murky blacks of low-grade digital cameras. There are images here that approach the nightmarish visages of Francis Bacon, or even Lynch’s Inland Empire, as well as some bits of low-key body horror and a disconcerting sense that some kind of impending violence is inevitable. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair isn’t really a horror film, despite some nods to Paranormal Activity, but it is terrifying as it dives deep into the darkest recesses of internet cognitive dissonance, that sense of total isolation even amidst perpetual connection. The film isn’t without a few missteps, including some odd, outre bits that play like remnants of miscellaneous short films and which interrupt the hypnotic spell of the main narrative, but there’s no denying the otherwise bold achievement of We’re Going to the World’s Fair and its heralding of an exciting talent in Schoenbrun.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

At the Ready

In light of the surging unpopularity of its subject matter, Maisie Crow’s sophomore documentary may come across as contentious and provocative in certain respects. Under the Trump administration, part of whose political mandate lay in tougher immigration laws, the U.S. border with Mexico was fortified with a wall; detainment of its illegal crossers, already a controversial feature under Obama, generated even greater public outcry. Within this context and that of more recent social justice movements against police brutality, it is, therefore, a bit of a novelty to behold a portrait of these very institutions much-reviled by liberal America. At the Ready is situated in the thick of action: El Paso, Texas, just ten miles from the border, and home to the country’s largest Mexican diaspora. Given its proximity to the threats of smuggling and illegal immigration, the city also boasts a robust police-education network, which includes drug enforcement and border patrol. The political significance of these conflicting identities is more than symbolic — the lives of the city’s inhabitants are thoroughly enveloped within them.

The film follows three Mexican-American teenagers and members of their high school’s Criminal Justice Club: Cristina, already graduated and on her way to a career in Border Patrol; Cesar, whose estranged father was himself arrested and imprisoned for drug trafficking; and Kassy (now Mason, since his coming out as transgender, which is noted in the film’s credits), the club’s commander. They hail from comparatively lower socio-economic backgrounds, so a job in law enforcement promises both financial security and a chance at a middle-class lifestyle. At school, their training comprises shooting exercises, search-and-seizure procedures, as well as hostage negotiations; in preparing for a national law enforcement competition and subsequently better job prospects, the trio must come to terms with the dissonance between their personal values and the occupation’s systemic realities.

Yet, for all its outward similarities with Steve McQueen’s deeply invigorating Red, White and Blue (about a black policeman’s struggle against the British police’s institutional racism), At the Ready lacks critical incisiveness; Crow seems content with presenting the inherent dilemmas her characters reckon with, without articulating their internal psychological developments. The film banks on pre-existing, politically polarized tensions — between ethnicity and employment, policing and permissive — to engender sympathy, and the seemingly refreshing ideological heterogeneity within a younger generation of enforcement agents belies its disappointing lack of insight. Cristina’s aversion to conservative strong-arming, for instance, merely renders her decision to follow through with her career puzzling (at least in the absence of any more material exploration); while Mason’s sexual orientation, which Crow devotes significant screen-time to, appears mostly tangential to At the Ready’s main thrusts. Though more centered around bringing criminals to justice than justly bringing them in, “Criminal Justice” swiftly gives way to the latter, working through the motions of talking-head discussions and distanced family profiles while leaving the most fertile sites for interrogation — in particular issues of racial and sexual dynamics within law enforcement — unexplored. At the Ready, while palatable, has little appetite for contesting or provoking debate.

Writer: Morris Yang

In the Earth

When Martin remarks at the wonder of being out of the house for the first time in four months, Alma, his guide into the woods in which they’ve made camp, replies that it’s only a matter of time before the COVID pandemic is over and people will quickly go back to behaving the way they always had before. Martin isn’t so sure, but Alma is certainly on to something: this is the first time Martin has left the house since the pandemic started, and already he’s willingly wandered into a forest rumored to be haunted. Come on, man.

In the Earth, the film Ben Wheatley directed during lockdown and between studio projects, is less about COVID than this early conversation might suggest, however, and blessedly a (mostly) straightforward horror story about the bad things that happen if you dare spend time in nature. Martin is setting out into the woodlands to assist on a research project with someone he hasn’t heard from in some time. Soon after he and Alma make camp on their first night, they are attacked and left injured; shaken, without shoes, and with miles left in their journey. Enter Zack, a man living in the woods, who offers them food and shelter in his large tent compound. But, of course, Zack isn’t what he seems, at least to Martin and Alma. Viewers will immediately guess what’s up with Zack and they’d be right: he’s an ax-murdering madman. And for the next stretch of film, In the Earth is refreshingly simple. First, Zack tortures Martin and Alma in scenes that are as funny as they are unnerving, and then the pair try to make their escape. This attempt is easily the highlight of the film, an uncomplicated and violent cat and mouse through the woods at night, complete with a grisly discovery or two, culminating in the first of several kaleidoscopic sequences meant to suggest that Zack isn’t the only, or even most, evil thing in these woods.

The second half of the film, more concerned with the centuries-old evil lying in the Earth, shifts into the realm of science fiction and paranormal investigation. In doing so, Wheatley loses the plot somewhat, as this relatively low-key section doesn’t have quite the same grasp on the first half’s simple pleasures and represents a too-long stretch between pitched horror pieces. Still, it mostly remains intriguing stuff, approaching occult evil with science and boasting a few more of those strobing montages set to Clint Mansell’s fuzzed-out score, which is used diegetically here. The tension and unease hold throughout, and it all culminates in another violent setpiece that is just as good as the one in the middle. That’s all to say, Wheatley is up to some pretty nifty stuff here. The film is unfussy and clean, with a necessarily limited scope that keeps the director reined in and creative. If there’s anything to take In the Earth to task for, then, it’s the very ending, which gets so wrapped up in psychedelia and ambiguity that it forgoes what really sings about the movie: direct and bruising horror.

Writer: Chris Mello

Taming the Garden

Salomé Jashi’s new documentary Taming the Garden begins with a striking image: as two men fish off of a rocky coastline, a giant tree cuts through the distant horizon, slowly creeping across the calm sea while standing fully upright on a barge. It’s both majestic and surreal, or, in Jashi’s own words, “It was beautiful, like real-life poetry, but at same time, it seemed to be a mistake.” File under “stranger than fiction,” as the film proceeds to detail the process of uprooting these stories-tall behemoths and transporting them to an entirely man-made personal forest of an unnamed billionaire. And it is a laborious, fascinating process, as Jashi locks her camera down in static master shots and observes men at work in all stages of this bizarre, Herculean endeavor. There are dirt roads and paths carved into the landscape, where the area around each tree’s roots has been excavated and then carefully wrapped in tarp and buttressed with lumber. There’s an elaborate system of metal pipes and tubing that are pounded horizontally through the ground which allow these massive objects to roll, before being lifted via crane onto the backs of flatbed trucks. These, in turn, creep slowly from forests to main roads and then finally the shoreline, to be loaded onto barges. Individual scenes are held for what seems like an eternity, typically observing one discrete action as it is performed from beginning to end. There are no title cards with information or talking-head interviews here; what contextualizing details there are can be gleaned in passing from conversations or must be entirely inferred from the images themselves.

Shot intermittently over the course of two years, Taming the Garden is not a typical issues documentary, but Jashi does have a point of view. Like the films of Nikolaus Geyrhalter, particularly Our Daily Bread and the more recent Earth, Jashi is simultaneously in awe of the insane endeavor unfolding in front of her camera but also well aware of the damage such processes inflict on both nature and the surrounding communities. It’s impossible to witness the deep gashes left on the landscape by huge pieces of equipment and be unmoved. She also gives screen time to various residents of the towns and villages where she’s shooting; some welcome the infrastructure that the project is bringing to their area, while others only care about the money they’re being paid to put up with the inconvenience. Still others worry about broken promises or the buyer backing out of due payments, while some are simply distraught that these natural wonders, some centuries old, are being removed at all. There’s also the matter of the anonymous person at the center of all this, who is unnamed in both the film and press materials. Several people in the film reference Bidzina Ivanishvili, the billionaire former Prime Minister of Georgia, although it’s unclear if this is known fact or merely idle conjecture. Jashi ultimately reveals the tree’s final resting place in the last few minutes of the film. A far cry from the controlled chaos of their uprooting, this artificial forest is calm, perfectly manicured, and maintained by an army of workers. It’s a startling contrast, although also beautiful in its own right. Left largely implied in-film, but lingering in impression long after, is the notion of a fabulously wealthy elite literally reconstructing the world according to their personal taste while the rest of us deal with the scars of their whims.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

First Date

First Date, the debut feature of directorial duo Manuel Crosby and Darren Knapp, has a gonzo sensibility that threatens, on occasion, to undermine its claims to baseline competency. The premise, without spoiling too much, goes as such: a questionable choice of car for a first date leads to overnight run-ins with cops, crime, and cocaine. Awkward teen Mike (Tyson Brown), who’s never had much success with girls, nearly meets with an accident while distracted by the sight of Kelsey (Shelby Duclos), his high-school crush; after some goading from his buddy Brett, he calls her and they agree to “hang out” later the same evening. Kelsey’s jock neighbor, to Mike’s chagrin, never ceases in his advances on her which she, in turn, never ceases to rebuff. The inexperienced homies, believing the automobile an absolute in the rulebook of attraction, set out for the nearest paint-moulted metal heap masquerading as a ’65 Chrysler. This shabby paint-job, unbeknownst to them, conceals much more. Soon, a swathe of criminal activity will encroach on the hapless virgin and upset his flights of fancy with Kelsey.

Like Adam Rehmeier’s Dinner in America from last year’s Sundance, First Date thrusts its off-kilter energy into full view, endowing an otherwise run-of-the-mill premise with a zany amateurism that’s simultaneously cool and cringeworthy. The former’s punkish adoption of cynical affectations à la Todd Solondz or François Ozon finds a kind of analogue in First Date’s placeholding romance: part-mumblecore, part-student film, its first few expository minutes inject such soulless infantilism through the near-unwatchable setup (more befitting of tween TikTok chat groups than adolescent conversations) that it almost appears suicidal to carry on. Luckily, the film’s grating hodge-podge of blurry and haphazardly spliced shots soon makes way for its comedic meat, cutting into territory charted through the uncanny dissolving of quirk and menace. Crosby and Knapp stretch the conceit of leaving a car’s shady history unresearched to what might be considered shaggy-dog limits; many unruly bad guys and untold bullets later, the car goes back to being someone else’s heap and Mike, else he risk their lives for nothing, finds himself liked by Kelsey. The entire story might have been otherwise content with its high-octane thrills and low-life shills, but as an awkward virgin himself, this writer really wouldn’t mind some sensual first-timing wedged in between.

Writer: Morris Yang

Comments are closed.