Come True is an empty-headed, poorly-conceived horror flick that mistakes endless stylistic detail for substance.

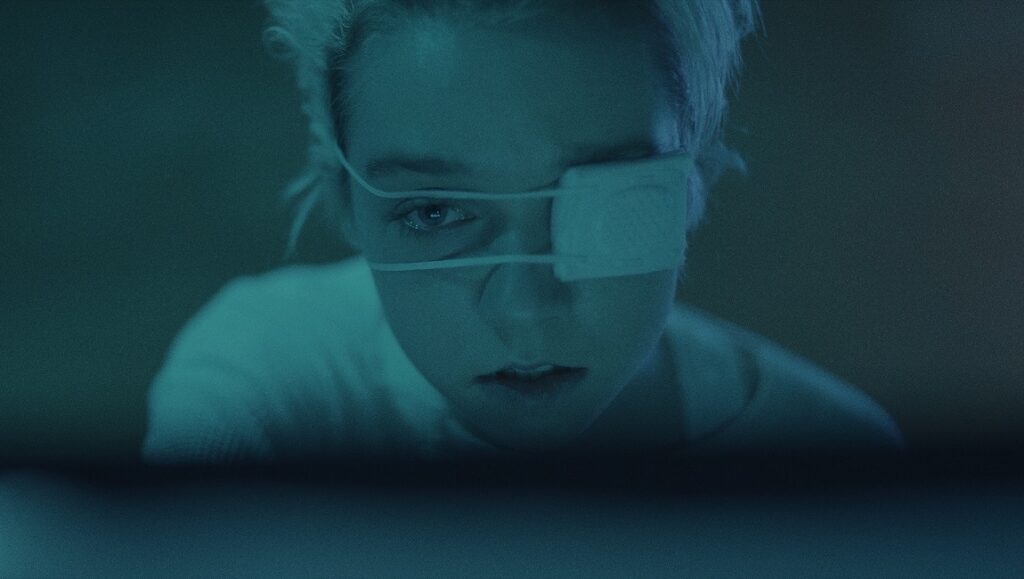

Anyone who has ever experienced night terrors can attest to the indescribable, otherworldly horror that only the human mind is capable of conjuring; to even attempt to replicate such a nebulous thing is a fool’s errand, one at which the Canadian export Come True fails miserably. Writer-director-cinematographer-editor Anthony Scott Burns works overtime to create a workable atmosphere of fear and dread, but succeeds only in delivering, quite ironically, a sleep-inducing fiasco unable to elicit even a single moment of terror. Employing a solemnity more suitably reserved for Holocaust dramas, Come True tells the tale of a troubled high school student whose participation in a sleep study unleashes all sorts of hell. Sarah (Julia Sarah Stone) is a teenage runaway suffering from night terrors, consistently plagued by visions of a dark, hulking figure with glowing white eyes. Answering a random flyer posted in the local coffee shop, Sarah becomes a test subject in a university study whose intentions seem suspect at best, all the more so once she finds her terrifying dream life seeping into the real world.

From the opening moments, it’s clear that Burns fancies himself an aesthete, an artist more concerned with style than developing his story and characters. In the horror genre, that’s not always a death knell; it is, however, an issue when said style is so wholly derivative of better artists’ work, a comparison that serves only to disappoint and distract rather than delight and frighten. Shades of Ken Russell and David Cronenberg are evinced throughout, with a pinch of David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows and its retro-modern fusion thrown in for good measure. Clunky, green-hued computer monitors and switchboards filled with blinking lights and sliding buttons fill the testing offices of the university, while modern-day cell phones and laptops pop into view when convenient to the plot. The team of scientists discusses how their revolutionary equipment is able to visually capture imagery produced in the mind during the dream state, but they conveniently fail to explain why it’s rendered with such lo-fi technology. Burns is so obsessed with these kinds of stylistic details that they soon become the film’s only focus, with anything resembling thematic interest — or, you know, delivering scares — apparently deemed moot. Why is there a Weekend at Bernie’s poster on Sarah’s wall? Why was the lone female researcher given such greasy and stringy hair? What is up with the head scientist’s look, bedecked as he is in turtlenecks, bulky sweaters, and the most ludicrously oversized tortoise-shell eyeglasses ever captured on film? And why exactly does the tableaux of dream sequences appear to have been wholly lifted from a circa-1999 Marilyn Manson music video, all monochromatic grays and hanging, mangled mannequin bodies?

Meanwhile, the plot bends over backwards to provide Sarah with a love interest, Jeremy (Landon Liboiron), a grad student overseeing the study and a character who seems to exist solely for a scene where Sarah can witness his hidden romantic yearnings play out on a computer monitor as he sleeps and she watches with bated breath, a soft electronica ballad filling the soundtrack. No thought has been given to how creepy all of this plays out, as Sarah is only known up until this point as a “high schooler.” When, in the next scene, she states that she is 18, it plays like little more than an inorganic segue to the subsequent graphic sex act, which uses full-frontal male nudity as a pathetically calculated reach for shock at the expense of any naturalism. The synth score, courtesy of Electric Youth and Pilotpriest, also feels like a desperate bid for cool points, a filmmaker’s attempt at relevance five years too late; all it manages to do is make the proceedings feel hopelessly dated, even as it strives for timelessness. Burns, for his part, saves the biggest insult for the film’s howler of a twist ending, a nonsensical kick in the balls that resituates the preceding 105 minutes as even more pointless than they initially seemed, a true accomplishment if ever there was one. There’s absolutely nothing of value or interest in Come True, a film whose idea of profundity is dialogue like, “It’s fucking scary, finding what makes us tick.” Trust me, there are scarier things.

Comments are closed.