OK, so things don’t really vanish anymore: even the most limited film release will (most likely, eventually) find its way onto some streaming service or into some DVD bargain bin assuming that those still exist by the time this sentence finishes. In other words, while the title of In Review Online’s monthly feature devoted to current domestic and international arthouse releases in theaters will hopefully bring attention to a deeply underrated (even by us) Kiyoshi Kurosawa film, it isn’t a perfect title. Nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to catch-up with films before some… other things happen.

My Salinger Year

Philippe Falardeau’s My Salinger Year is the film adaptation of Joanna Rakoff’s memoir of the same name, depicting the author’s year spent working for the literary agency that represented author J.D. Salinger in the late 1990s. After hiding her literary ambitions, Joanna (Margaret Qualley) is recruited as a clerical assistant to Margaret (Sigourney Weaver), abandoning her college sweetheart in favor of a new, bohemian lover, Don (Douglas Booth) and committing to her New York dreams. Under the benevolent shadow of Salinger and his legions of adoring fans, whose every letter is read (and promptly shredded) by Joanna, she reckons with not only her sense of self, but also her craft and identity as a writer.

Much like every element of the film, Joanna and the people she surrounds herself with are beautiful relics, people who feel so uniquely of a time and place that it’s hard to imagine them existing anywhere else. Whether it’s Joanna nonchalantly dropping out of college with the vague promise of a job that nowadays would be fought for, tooth-and-nail, or Don’s blissful ignorance of every cliché he so blithely stumbles into, the world of My Salinger Year simply does not exist anymore, lost to self-awareness and the internet era’s distinct brand of cynicism. Qualley, Weaver, and Booth uniformly reject such cynicism, taking archetypes of the literary world (the wide-eyed ingénue, the shrewd agent who takes no prisoners, and the self-indulgent, self-interested male writer), and embodying them with sincere empathy, despite the alternative perhaps being a far easier strategy. Instead of following in the footsteps of obvious predecessors, such as The Devil Wears Prada, My Salinger Year reflects on its characters kindly, and in doing so, offers a rose-tinted worldview that is likely to charm as many viewers as it bores.

The unique cocktail of casually opulent hotel lobbies and earth-toned offices that Qualley floats through harkens back to a bygone era, just as the film’s characters cling to it and try to stop it from drifting away. The world of My Salinger Year is one preserved perfectly in amber, with comforting earthy tones and a permanent autumnal feel permeating the New York spaces where Joanna spends much of her time. In tandem with the gentle romance of Martin Léon’s score, which makes the film feel positively buoyant, director Philippe Falardeau has here fashioned a love letter to both literature and to those who are so earnestly shaped by it.

Writer: Molly Adams

The Vault

Best known as the writer and director of three of the four films in the found-footage horror series REC, Jaume Balagueró makes a huge leap in scope and ambition with his new heist thriller The Vault (releasing in some parts of the world under the equally generic title Way Down). Beginning with a brief prologue set in 1645, as a sinking ship loses its cargo in the depths of the sea, the film skips ahead to 2009, where a salvage crew is attempting to retrieve the now long-lost sunken treasure. Led by the tough, taciturn Captain Walter Moreland (the great Liam Cunningham) and his right-hand man James (Sam Riley), the team secures the loot but is caught by the Spanish Coast Guard. After an international legal battle, the courts decide that the Spanish government has the rights to the treasure, not Moreland’s salvage crew. Undaunted, Moreland decides to steal the treasure back for himself. Using some outlandish, but fun, cloak and dagger nonsense, Moreland reaches out to Thom (Freddie Highmore), a brilliant engineering student who he thinks will be able to help him break into the most secure vault in Europe, located in and under The Bank of Spain. The issue, as Moreland describes it to Thom, is that they have to solve a problem, but they don’t even know what the problem is. The vault is almost a hundred years old, and so contains no modern technology to hack or drill, and is instead a mysterious feat of engineering that has never been seen from the inside. Having already assembled the rest of the team — the aforementioned James, art expert/honey trap Lorraine (Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey), tech guy Klaus (Axel Stein), and equipment handler Simon (Louis Tosar) — Moreland and Thom lay out two different plans, the success of one necessary to the success of the other. First, getting information and schematics about the vault itself, and then how to get in and out of it, if such a thing is even possible.

All of this is set against the real-life backdrop of Spain’s national football team making a historic run-up to the World Cup finals in 2010, the eyes of the nation distracted enough for this crew to pull off their ambitious robbery. The film has five credited screenwriters, but miraculously the narrative is cohesive, following a strictly linear chronology that has the team devise and then execute multiple small missions, each of which adds up to part of the overarching master plan. The detailed plot is an intricate feat of engineering itself, with clear goals and a keen sense of geography as team members spread out and infiltrate multiple parts of the bank simultaneously. Unfortunately, there’s nothing anyone can do to make Thom an interesting character. He’s clearly intended as a kind of audience surrogate, allowing different characters to explain terms and techniques to this young novice in what amounts to straightforward exposition. But Highmore is a black hole of charisma, a deeply uninteresting actor who stops the movie cold whenever his character becomes the focal point of a given scene. The Vault is still a lot of fun, obviously indebted to Ocean’s Eleven and The Italian Job but with the slick veneer and sleight of hand of Now You See Me, but this unfortunate bit of casting keeps it from being more than just an engrossing lark. Still, sometimes that’s enough.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Happily

The law of diminishing returns dictates that, over time, optimal output will ultimately level off as new variants are introduced into the equation. The same goes for relationships; the feeling of euphoria present at the start will eventually taper off as the everyday minutiae and familiarity of life take their toll. Sustained happiness is suspect, an idea explored in Happily, writer-director BenDavid Grabinski’s impressively assured debut. Tom (Joel McHale) and Janet (Kerry Bishé) have been blissfully married for 14 years, remaining as happy as they were on the day they met. They have sex, on average, 2.5 times a day, and that’s not even including oral. They instantly and truly forgive one another’s minor transgressions. Their marriage is, in a word, perfect. It’s also the reason why they are so hated by their friends, who see their love as a sort of betrayal of nature. In a nod to the likes of The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, the couple are soon confronted by a stranger who informs them that their happiness is indeed a genetic malfunction in need of scientific correction. What results puts a whole new strain on their upcoming weekend getaway with friends, all of whom have plenty of dirty laundry in need of airing.

Grabinski possesses a keen understanding of the toll that, ironically, happiness can take on both a relationship and those troubled souls exposed to it. We want to believe that each person is as miserable as the next as we deal with the struggles that accompany any long-term romance. Happiness is fleeting, a façade held in place by the most delicate of threads. If all of this sounds rather weighty, what proves most impressive is the light touch with which Granbinski and his talented cast execute the conceit, also eliciting a surprising amount of empathy for its flawed characters. And above all else, the film is legitimately, wickedly funny, inspiring more laugh-out-loud moments than any comedy in ages. Grabinski has fun with his widescreen compositions, delivering a number of clever sight gags that take full advantage of the sprawling visual space. In a rather humorous nod, he also apes the aesthetic of David Fincher’s Gone Girl, cool blue filters contrasted with scenes of glowing golds and ambers — and he even has some fun with the kind of ridiculously oversized shower that proved pivotal in Fincher’s portrait of an unhinged marriage. McHale delivers what is undoubtedly the most genuine performance of his career, and he and Bishé evince a believable and palpable (sexual) chemistry. They’re buttressed by a stellar supporting cast — including Natalie Morales, Paul Scheer, and Charlyne Yi, to name a few — all of whom seem both entirely relatable and wholly awful, an apt enough reflection of our own petty natures. The whole thing is an exercise in uncanny instincts, but when a film manages to effectively use the theme song to Walter Hill’s 1984 cult classic Street of Fire during its climax, or pull off lines like, “He has worse taste in music than the jet from the movie Stealth,” you know it’s truly special. With Happily, Grabinski proves that, even in his debut, he is already a master of tone and a serious filmmaker to follow.

Writer: Steven Warner

Exodus

Exodus, the debut feature by cinematographer-turned-director Logan Stone, is a peculiarly insular version of a standard post-apocalyptic thriller. Stone’s vision of America seven years after the Rapture is nearly indistinguishable from any number of decaying post-industrial towns that currently exist, complete with burned-out cars and a suitably somber color palette. In fact, the standard hallmarks of American culture — rugged individualism, a thriving prison system — seem to be all the more necessary for maintaining order in a world where most of the population has inexplicably vanished.

The film’s small cast of characters are preoccupied by the presence of a VHS tape that leads viewers to a mythical door to paradise. It’s unclear how much the characters know about what lies beyond the door; nor is it clear how life sustains itself for those left behind. Defectors are imprisoned and intimidated by a woman called “The Emissary” (Janelle Snow), who works for the same prison that employs Connor (Jimi Stanton). They forge an uneasy alliance when Connor finds the tape and leaves his ailing brother to search for the door.

At a slight 75 minutes, Stone raises far more questions than he’s interested in answering. He centers the film around a VHS tape and, to a lesser degree, a pager, making it unclear when the film takes place and what tools the remaining townspeople have at their disposal (beyond guns, which they seem to have in abundance). As Connor plunges further into the desert and meets other travelers, all searching for the door themselves, the film’s logic starts to unravel. Special effects are deployed to hint at the door’s significance without revealing anything about what it means or where it leads, leaving audiences as bewildered as the rest of the wanderers but with none of the same emotional investment.

It’s tempting to read the film as something of a capitalist critique, with the post-Rapture world representing a decrepit Rust Belt town blighted by unemployment and generational migration, and the door serving as an escape hatch towards gainful employment and a secure, comfortable future. Unfortunately, there’s no indication that Stone intended for such an interpretation — or any other, really. Ultimately, Exodus leaves audiences spinning in circles, grasping for meaning but unlikely to find anything of substance.

Writer: Selina Lee

The Winter Lake

Set in a rural, rain-soaked Irish countryside, Phil Sheerin’s The Winter Lake starts solidly enough. As the film focuses mostly on the cold and bleak natural landscapes, boasting a dark green and blue palette, it’s apparent that Sheerin’s main intention here is to form an atmospheric thriller, one that pushes its narrative to the background in order to focus on its four principal characters and a mystery that disturbs the tranquility of this faraway place. The problem is, as the film progresses, it never quite finds much that it can convincingly or effectively substitute for its lack of suspenseful story. The actors do their best to vividly embody their troubled, if slightly scripted, characters, particularly seen in the relationship between young, angst-ridden Tom (Anson Boon) and girl-next-door Holly (Emma Mackey, whose mysterious rebel lassie here recalls her role as Maeve in Netflix’s Sex Education), who harbors a dark secret that Tom soon uncovers. Unfortunately, Sheerin and screenwriter David Turpin do little to cultivate these characters from one scene to another, and the plot tries to unravel itself through unconvincing and unengaging dialogues that strive only to keep everything vague until the very end.

So, while the lack of a reliable story fails to develop any suspense, Sheerin opts for the easiest and quickest solution: allow August Murphy-King’s eerie electronic soundtrack to imbue a superficial, nihilistic ambiance throughout the film and let the tense theatrics escalate, placing everything under the heavy pressure of sobbing and shouting, before characters suddenly tune to radio silence in the second half. The somber visuals are excessively dark (often almost to the point of pitch-blackness), and oppressive quality reflects the film itself: the longer The Winter Lake goes on, the harder it becomes to care about what’s happening on screen until the point it reaches its predictable “climax” and flat, passive conclusion. Sheerin’s relative inexperience — having only directed a handful of short films — could explain some of this mishandling, but also to blame is that the film oscillates so unevenly between British realist, familial drama (think Ken Loach, for instance) and moody folk horror, each element effectively neutralizing the other. These days, it’s quite common to lazily categorize or vindicate a film like this with the label of “slow-burn thriller.” Sure, The Winter Lake is indeed slow, but it doesn’t have enough in its tank to sustain that measured pacing for any length of time, leaving things flat. In the end, it offers little that either burns or thrills.

Writer: Ayeen Forootan

Pixie

After spending the last few years delivering stellar second-fiddle performances, Olivia Cooke steals the show in Pixie as the eponymous character, a witty and equally dangerous daughter of an Irish gangster, out to avenge her mother by stealing a holdall of cash and fleeing the country to follow her dreams in San Francisco. As far as revenge plans go, it’s far healthier than the trail of bodies left in the wake of most revenge-movie heroes, but even the best-laid plans can go awry, and Pixie’s quickly does. Cooke plays the role with infectious glee, her easy smirk belying an easy confidence and very present threat: it’s the sort of role any actress would kill for, but not one that just anyone could pull off, particularly as well as Cooke does. After she enlists two young men who are both helplessly infatuated with her (Ben Hardy and Daryl McCormack), the trio go on the run with a bag of drugs, pursued by deadly gangster priests (led by Alec Baldwin). Though it might sound like the screenwriters simply filled in a Guy Ritchie mad-libs sheet to come up with the plot, Pixie manages to stay on the right side of quirky, never straying into outright cutesy territory. While the film is decidedly a showcase of Cooke’s star-quality, and none of the cast ever steal her limelight, Hardy and McCormack still hold their own as Pixie’s sidekicks, while Turlough Convery’s malicious, snarling older brother continues his effort to become the UK’s most immediately villainous actor.

While I’m sure nobody asked for Ireland’s answer to the Tarantino-lite, heist/gangster film, Barnaby Thompson’s Pixie is a joyride that manages to be exciting, touching, and even occasionally thrilling. John de Borman’s cinematography makes the most of the rolling Irish countryside, casting Pixie in contrast to the Westerns it evokes. Opening with “Once upon a time in the west… of Ireland” in bold lettering, and Pixie’s subsequent vow of vengeance, you might expect something with a touch more grit or gravity, but Pixie fully embraces its own absurdity. While it may not boldly subvert the genre, Pixie is a colorful, sly addition to a Tarantino and Ritchie lineage of films that is soaked in equal amounts of wit and blood.

Writer: Molly Adams

The Devil Below

Being a horror fan is sometimes like taking a leap of faith, willingly subjecting oneself to reams of cheap, bottom-of-the-barrel monstrosities while desperately digging for that elusive diamond in the rough. The Devil Below isn’t that hidden gem; honestly, it’s destined to become anonymous streaming fodder and not much else. But when you’ve seen as many bad movies as we have, even basic competence should be celebrated, and here, director Bradley Parker shows he’s got some decent chops. After a brief prologue of some good ol’ boy miners knocking off after a hard day’s work, only for one of them to get snatched by an unseen something with nasty claws, the film jumps ahead and introduces Arianne (Alicia Sanz), a tough-as-nails guide who helps people get to places that are off the grid or otherwise hidden away. When a team of pretty-boy scientists hire her to squire them to an abandoned mine deep in Appalachia (we know the one), they discover that the place has been wiped from the maps, find all routes to and from obstructed, and encounter a surly group of locals who claim to have never heard of the place while also warning them not to go snooping. Of course that only encourages our intrepid explorers, but what they find is worse than they could’ve imagined.

So, it’s a solid setup, and Parker, along with screenwriter Stefan Jaworski, keeps things moving at a brisk enough pace. The acting is variable at best, with Sanz and team leader Darren (Adan Canto) the only two making much of an impression. Once they get to the mine, they find a series of electrified fences and locked gates that seem designed not to keep people out, but to keep something in. Sure enough, these idiots let out a bunch of monsters, and they start getting picked off one by one. There’s a healthy dose of both Aliens and The Descent here, although no one spends much time underground. Instead, the film switches gears, and the townspeople spring into action to keep the monsters at bay. It’s here that the film really runs into trouble, as the filmmakers use every trick in the book to obscure their obviously tiny budget. The creatures are shrouded in darkness or glimpsed only in quick flashes. Attacks happen offscreen, or are obfuscated by smeary, blurry CGI. Eventually, the survivors encounter the creature’s Queen, in a series of illegible sequences where it’s virtually impossible to tell what’s happening. From a distance, the creatures are clearly people in rubber suits, while a few lightning-quick flashes of their gaping maws suggest a variation (or rip-off) of the beasts from Stranger Things. There’s some moody atmosphere and a couple of okay action beats along the way, but eventually you’ve got to give your audience the good stuff. The Devil Below fails that most basic of genre tenets, without even any real gore to get that lizard part of the brain cheering. Give these guys some money, and let’s see what they can really do.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

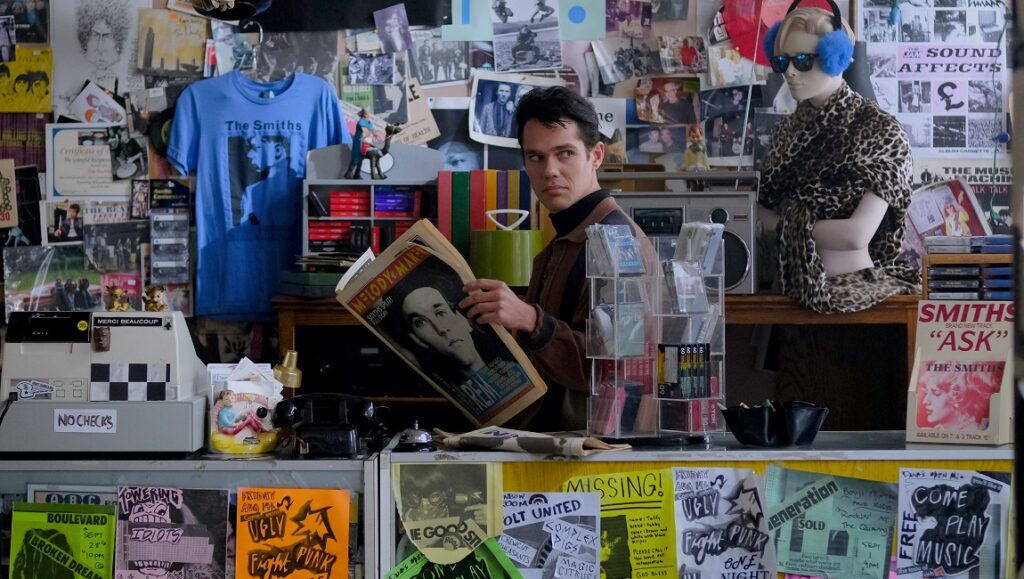

Shoplifters of the World

Set in 1987, Stephen Kijak’s Shoplifters of the World follows four friends on what might be both the most catastrophic day of their young lives so far — the day The Smiths broke up — and also the most interesting night, with a passionate Smiths fan taking a local radio DJ hostage and forcing him to play the band’s greatest hits all night long. The quartet drift from party to party, followed everywhere by Morrissey’s dulcet tones, their goals and half-formed identities colliding as they struggle with who they are in the wake of the disintegration of a band that helped shape their own understanding of their lives.

So far, so good — while a film like this might not appeal on the strength of its synopsis alone, given the iconic music at its center and the familiar coming-of-age framework, Shoplifters of the World has plenty of promise. Originally boasting an impressive ensemble cast including Will Poulter and Thomas Brodie-Sangster, and with Kijak a director well-acquainted with films centering on both music and obsessive personalities, expectations were high. However, nine years and several recasts later, what remains of that considerable potential is effectively a 90-minute music video. Glimpses of the film that might have been are glimpsed in this aesthetic, and in Joe Manganiello’s performance as Full Metal Mickey, the hostage radio-host. Also acting as a producer on the film, Manganiello strikes the comedic tone that the rest of the film is sorely lacking, balancing over-the-top dialogue with a sincere insight into the hero worship and music-obsessive ethos that the rest of the characters are contending with, and his scenes are by far the most watchable. The rest of the cast are left with lines that wouldn’t feel out of place in a cheap jukebox musical — cringe-worthy, of course, but lacking the charm that often makes those films so enjoyable. The script might have gotten away with more if the actors ever seemed certain as to whether they want us to laugh at or with these characters — more often than not, the result is the former.

Given its fantastic, built-in soundtrack and music-video aesthetics, Shoplifters of the World could conceivably become a trashy cult classic, but that still says little about its quality. As written, the film blurs the line between campy melodrama and something altogether more sincere, and despite having undoubtedly good bones, it distinctly fails to live up to its promise. There’s little here that’s memorable, and it’s never a great sign when it’s hard to even ascertain which disappointing element of the production is most to blame. Maybe the only thing to be said for it is that it achieves one of the key aims of any music-based movie of this ilk — you’re sure to leave Shoplifters of the World remembering just how brilliant The Smiths were.

Writer: Molly Adams

Comments are closed.