Dark Red Forest

Spiritual faith, by virtue of its abstract and elusive qualities, rarely translates well to the visual medium, if indeed it can be translated at all. Depictions of this faith have ranged from the sacred to the sacrilegious, articulated with either austere minimalism or gratuitous violence. Applying the former to his ethnography of Tibetan Buddhism, Jin Huaqing exemplifies a fidelity to the ethics of representing belief systems from an external vantage point, though his austere fidelity may come at the cost of accessibility. Shot over a year, beginning in the winter of 2017, Dark Red Forest documents the spartan and secluded lives of nuns from the Yarchen Gar Monastery as they brave both the harsh elements and an encroaching political intolerance towards their religious practice. Numbering more than ten thousand, the nuns congregate over the Tibetan New Year for sermons and instructions from a guru, having over the preceding winter — during the coldest hundred days of the year, specifically — lived in isolation across the Tibetan Plateau, segregated in wooden huts for meditation and spiritual retreat. Draped in dark red robes, they lend the film its title: a community of practitioners seeking enlightenment and attaining it through months and years of solemn routine.

In training his lens onto this routine, Jin renounces the metaphysical grandiosity favored by certain filmmakers of the sublime such as Carlos Reygadas, whose works are directly invested with a dialectical confrontation between spiritual transcendence and bodily immanence; insofar as Dark Red Forest adopts a curious but dispassionate gaze, it separates viewer and subject, and assumes a respectful, opaque objectivity in portraying the latter’s internal negotiation with principles of higher truth. “There is no real suffering in the world. People only suffer because of their obsessions,” contends one of the nuns, encapsulating their gruelling faith. Considered nonetheless a rare and prized honor, nunhood entails, through its relative proximity to enlightenment, the heavy responsibility of saving all beings from suffering. As believers pray for the forgiveness of sins and the release of souls from the dead, the Buddha’s karmic teachings are followed and life’s apparent moral randomness can be reconciled with.

The film’s most captivating sequences occur at dawn and dusk, when Jin’s camera surveys the forbidding plateau landscape, littered with the huts of nuns deep in retreat. There’s an arresting beauty and profundity in this impressive and expansive silence, which is arguably the strongest emotional connection proffered to the religious outsider. For the most part, Dark Red Forest commits to sociological survey, observing but never interrogating the nuns’ habits, ranging from the metaphysical to the medicinal. This survey also extends to the specter of state repression with a hint of wry irony, where nearby Communist-styled billboards proclaim such propagandist platitudes as the “eternal flourish of unity and amity among the Chinese ethnic groups,” and where the monastery’s instructions to consistently meditate preclude sickness and the intrusion of “government people.” One wishes Jin further developed his film on either political or spiritual lines of inquiry; as it stands, Dark Red Forest rarely integrates the two, preferring an unintrusive presentation of each. And perhaps, at least where spiritual abstraction is concerned, there lies the limit; in a subtly harrowing sequence midway through the film, an act of symbiosis is depicted, and it is up to the viewer to discern and define it.

Writer: Morris Yang

Credit: Taskovski Films

Radiograph of a Family

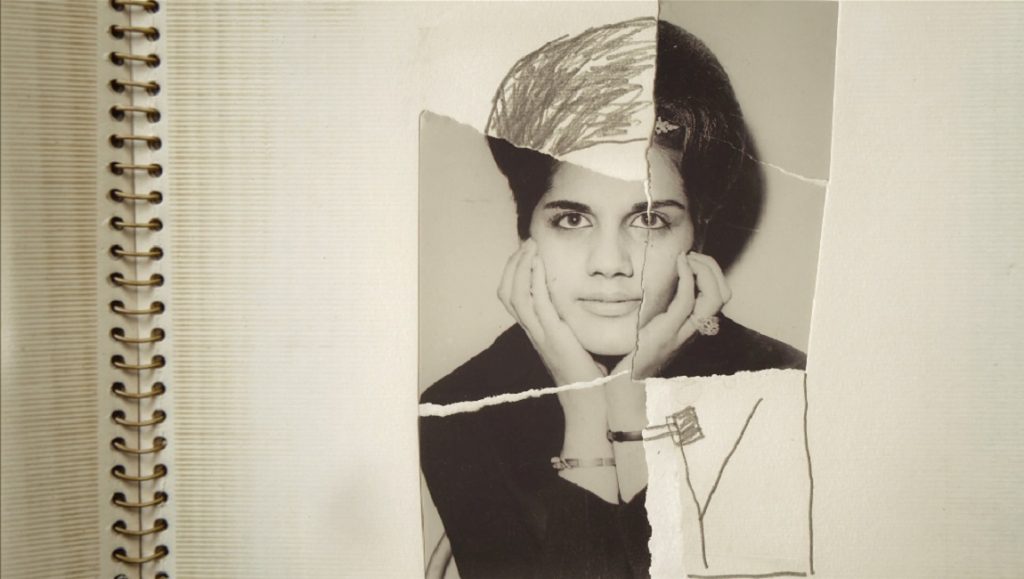

Firouzeh Khosrovani’s documentary Radiograph of a Family opens with an image that is both hook and omen: her mother’s wedding in Tehran, as she is being married not to a groom, but to a picture of her father, Hossein. While this is explained as a necessary compromise so as to not impede her father’s radiology studies in Switzerland, it points to an essential divide between Tayi and Hossein which the film aims to explore and evoke, between separate cultures, countries, and ways of living. Spanning an uncertain amount of time between their first meeting and Hossein’s death, the film, which won Best Feature-Length Documentary at IDFA 2020, invokes a series of wider sociopolitical issues within its shifting style, to both its benefit and its detriment.

In the absence of a plethora of footage of her father and mother, Khosrovani has opted for a more elliptical approach, relying mostly on photographs and repurposed Super 8mm footage, which have been overlaid with her own voiceover, scripted conversations between her mother and father recreated by actors, and music and sound effects that neatly interweave with the frequently blurred and degraded images. This hazy footage is deliberately contrasted with a pristine recurring image of a house that evokes the family home in Tehran, which is always shot via a slow tracking shot and redecorated throughout the film to represent the different states of the family’s living at the time.

Radiograph of a Family is fundamentally the story of constantly clashing views on religion and lifestyle: Hossein embraces Western culture and no longer seriously practiced Islam by the time he met his wife, while Tayi is a devout Muslim who undergoes an identity crisis when she begins married life in Switzerland. After the couple move back to Tehran to give birth to Firouzeh, Hossein largely recedes into the background, as Tayi discovers the teachings of influential revolutionary Ali Shariati, and soon after joins the Iranian Revolution and becomes a figure of minor prominence within the movement, devoting herself more and more to the cause as Hossein’s previous disregard for his wife’s requests is forced to diminish.

Throughout, Khosrovani latches onto intriguing details that point to a fittingly polarized experience of homeland and identity: when they initially return to Tehran, the friends that Hossein frequently host seem to Tayi to be far more reminiscent of Switzerland than the Tehran that she grew up in, and at a crucial juncture the two speak French to each other, in order to keep the conversation from Firouzeh’s ears. But while Radiograph of a Family is consistently well-crafted, it often risks reducing the complexities of the director’s parents and their relationship to a fundamental incompatibility, evident from the very first dismissal that Hossein makes of Tayi’s adherence to Islamic customs.

With practically no middle ground established in the film, it frequently lacks a strong and fully-formed viewpoint, which makes the personal aspects rise to the surface only fitfully. The people, and thus the cultures they represent, seem to be incapable of interacting in a harmonious manner, a sentiment which might have considerable weight if it was more willfully emphasized or deemphasized. Still, Radiograph of a Family encourages a complicated but ultimately admirable ambiguity, a state of inbetweenness experienced first by Tayi and then by Firouzeh herself, where the quest for self-discovery can be illustrated in a potential home movie here, a tinny audio recording there.

Writer: Ryan Swen

All the Light We Can See

Pablo Escoto’s All the Light We Can See comes with a bibliography in its end credits, a kind of road map to its poetically cryptic approach to narrative. An experimental film in the truest sense, it’s simultaneously epic and intimate, like a community theater production writ large. With what amounts to a couple of pre-existing locations, a few costumes, and a horse, Escoto manages to conjure an entire universe via a series of elliptical, sometimes abstract vignettes. It resembles a magic trick of sorts, a jumbled confluence of various influences both cinematic — Ruiz, de Oliveira, Rivette, and Straub/Huillet come immediately to mind — and literary — Frederico García Lorca’s Blood Wedding, as well as Roberto Bolano, Hannah Ardent, Efraín Huerta, Gerardo Arana and his posthumously published Meth Z, and revolutionary texts from the Zapatistas, are all among the bibliographical entries. The film is neither beholden to nor an adaptation of any of these precursors; indeed, part of the film’s strange, idiosyncratic beauty is how personal it feels. Instead, then, they function like suggested entry points and intellectual building blocks; another suggestive avenue comes from critic Ela Bittencourt, who describes the film as “like being lost in a Shakespearean forest when protagonists are both in character and somehow our contemporaries, as manifestations… slipping in and out of mythic roles.”

Serving as a prologue to the film proper, a narrator (actually Escoto’s own voice) relates the mythological tale of two lovers, Popocatépetl, a young peasant, and Ixtaccihuatl, a beautiful princess. Popocatépetl goes off to war to become a noble and become worthy of Ixtaccihuatl’s royal status. Time passes, and believing he has died in battle, Ixtaccihuatl commits suicide. When he finds her lifeless body, Popocatépetl begs the gods to keep them together forever, and the two are transformed into volcanoes — she dormant, he active. The valley between these two peaks becomes Escoto’s playground, as he follows separate plots unfolding under the auspices of these symbolic monuments. Rosario (Margarita Chavarria) mourns the death of her older lover, a General, and sits guard by his gravesite. Meanwhile, Maria (María Evoli) flees her wedding to the malevolent El Bandido (Lazaro Gabino Rodriguez) with her true love, El Toro (Inigo Malvido). The Bandit pursues them, although the leisurely pace by which the couple traverse the countryside suggests an Edenic revelry more than a chase. These stories eventually intersect, and the film moves from day into night, taking on a dream-like ambiance in the process. Working with cinematographer Jesus Nunez, Escoto utilizes a variety of digital textures to defamiliarize the landscape, shifting from the pictorially beautiful to the starkly monochromatic. By the time night falls, scenes are illuminated by only a single harsh spotlight, creating a kind of pixelated chiaroscuro as characters are seemingly carved out of the darkness.

Toward the end of the film, Escoto’s narrator returns to detail the Zapatista uprising in 1994, where rebels descended from the mountains into the cities and released a manifesto demanding basic human rights. The same year, in a bit of cosmic synchronicity, Popocatépetl erupted after 70 years of dormancy. Meanwhile, NAFTA was also signed in to law in January 1994, an unrelated act that nonetheless gains some resonance in hindsight. After all, NAFTA would lead to an explosion of low-paying factory jobs in Juarez, Mexico in the years to come, which would in turn eventually become the site of hundreds of unsolved murders. This horrific bit of history is, of course, the basis for Bolano’s magnum opus 2666, itself a model for the kind of diffuse narrative gamesmanship Escoto is attempting here. Following this kind of vaguely conspiratorial interconnectedness can elucidate as much as it obfuscates, and Escoto provocatively juxtaposes all these disparate threads into a wide-ranging survey of our current era. By causally linking mythology, 19th- and 20th-century literature, radical politics, and a very particular strand of modernist art cinema, Escoto collapses these historical modes into a new form, an elegy for the past that still looks forward toward the future. The gods won’t save us, so we must save ourselves.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Credit: Juja Dobrachkous

Bebia, à mon seul désir

Coming from the world of short fiction, Juja Dobrachkous made her debut as a feature film director with Bebia, à mon seul désir at the most recent IFFR, and now brings the film to the latest edition of MoMA and Film at Lincoln Center’s prestigious New Directors/New Films festival. One can almost immediately see what attracted the festival’s curatorial team to Bebia, this film bearing a remarkable, stark visual aesthetic from its opening moments, an impressively considered widescreen canvas in crisp black and white. It’s an imposing aesthetic, deftly rendered by Dobrachkous and her cinematographer Veronika Solovyeva, that at times recalls more established contemporary arthouse filmmakers like Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Paweł Pawlikowski rather credibly (some quick internet research suggests Dobrachkous has been involved with the industry for nearly as long in other capacities, seemingly production design for Sergey Livnev in the ’90). Yet, Bebia is frustrating too, the height of its formal accomplishments contrasted sharply with a woefully simple script that reflects very little of the thought and attention apparent in Dobrachkous’ visual composition.

As implied by the black and white palette, Bebia is a film that wants to contend with extreme binaries, reckoning with gender roles, urbanity and rusticity, commercialism and tradition, life and death… The film’s title character has passed on by the time the story opens, her death the impetus for her granddaughter (and the film’s protagonist) Ariadna (Anastasia Davidson) to return to the Georgian village where she was raised. Through flashback we learn of the abuse and degradation Ariadna experienced under Bebia’s (Guliko Gurgenidze) guardianship, cruel projections of internalized misogyny that would eventually drive Ariadna to flee the countryside in pursuit of a modeling career. Nevertheless, she returns home to grieve only to find that her grandmother’s death is not only complicated by traumatic memory, but by a traditional obligation forced on to Ariadna as Bebia’s youngest descendant, requiring her to tether a string between the deathbed of the deceased and her final resting place — a 25 km distance that must be covered on foot. Various motivations ensure that Ariadna keeps to this journey, which, of course, is as much about her own catharsis as it is spiritual fulfillment, but it’s one that becomes easy to lose interest in once its clear that Dobrachkous isn’t really interested in investigating her characters’ interiorities. Instead, the writer-director seems to get hung up on the superficialities of these dynamics, often taking the narrative towards miserablism and catering to an outsider’s conception of life in rural Georgia (Dobrachkous herself is Russian and based in London). This incuriosity isn’t apparent in the patient rhythm of Dobrachkous’ edits — really refreshing to encounter a new director who’s good about holding their shots — nor the precisely framed, expertly scaled landscape shots (where the Ceylan comparison comes in) threaded through dreary exposition and tired metaphor. There are other neat visual ideas at play here (directionality especially — the aspect ratio favors horizontally-oriented shots that are brought into conflict with those conceived on a vertical), and when taken in total they suggest a significant vision, but it’s one that isn’t particularly well matched by the ideas in the writing.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Gull

Kim Mi-jo‘s debut feature, the stark social-realist drama Gull, may be a slight 75 minutes in length, but it packs quite a powerful punch across this brief runtime. The film’s protagonist, O-bok — portrayed with unvarnished intensity by Jeong Ae-hwa — is the prototypical Korean ajumma, the tough, middle-aged woman who often has a fierce, prickly exterior, and whom you mess with at your peril. She works at an outdoor fish market in Seoul, and as the film begins, the middle of her three daughters is about to get married to the son of an affluent government official. O-bok and her fellow merchants, meanwhile, are in the midst of a fight with their landlord over a gentrification plan that threatens to rob them all of their livelihoods.

O-bok relieves herself of these daily pressures by drinking with her friends and some of the other merchants at the end of her long work day. On one of these nights, she’s sexually assaulted (presumably after getting drunk) by Gi-taek, a merchant who’s the lead organizer of the gentrification fight. This rape happens offscreen, but we see the aftermath effects: O-bok stumbling home afterward, her haunted and ravaged demeanor, the bloodstains that she furiously tries to make disappear. Gull immerses us in the pain, shame, and silence often imposed upon rape victims in the South Korean society Kim depicts. (It goes without saying that these circumstances are by no means limited to this one specific country.) O-bok at first tries to hide what’s happened, but those around her can’t help but notice that something is wrong. Finally, unable to remain silent any longer, she confides to her middle daughter that she’s been raped, but begs her daughter not to tell her husband, and strives to keep this from her future in-laws. O-bok’s daughter convinces her to report her rape to the police, although she’s reluctant at first.

Gull impresses with its meticulous examination of how rape victims, especially older ones like O-bok, are continually failed by institutions, individuals, and even their closest loved ones. The police are basically useless; they insist that since O-bok has no physical evidence, there’s nothing they can do. The other merchants, including those who were with her on the night of the assault, refuse to help her, and want her to keep quiet, afraid that this will hurt them in their battle against the landlords. O-bok’s husband, having heard about the rape police report, not knowing his own wife was the victim, says that women who claim rape actually really want sex too, eliciting a furious response from O-bok when she hears this. Even her own daughter, in a frustrated moment, blames her mother for getting drunk and putting herself in a position to be raped. The title of this work, obliquely referencing Chekhov’s The Seagull, proves to be bitterly ironic. Unlike that avian creature, O-bok can’t simply fly away from the tragic, isolating, and ostracizing circumstances of her life. Rather, she’s forced to be tethered to the ground, and to become a silent, solitary, sandwich board-wearing protest march of one against both the man who raped her and the society that refuses to heal her pain or even acknowledge that it exists.

Writer: Christopher Bourne

Credit: Film at Lincoln Center

Liborio

Olivorio Mateo, a farmer-turned-prophet whose providential oversight and teachings later influenced the Liborista movement, is the subject of Nino Martínez Sosa’s sophomore work, Liborio (named so by his followers). The occasion of his disappearance during a hurricane, and reincarnation as a mystic, gifted with powers of healing, provides an opportune lead-in to the film’s manifold dalliances with the supernatural and totemic. His return, growing sphere of influence within the Dominican South, and the military clampdown precipitated by his commune’s refusal to yield to colonial rule, are related through the lenses of six different followers. Each represents a singular set of coordinates by which to locate and authenticate the figure of Liborio, whether through Eleuterio’s clandestine entry into the private world of his master’s rituals or Plinio’s naïve assimilation of his belief system; their levelled perspectives in accordance with the principles of egalitarianism and collectivism encoded in his faith. All, however, remain expectedly distanced and disarticulated. Sosa’s approach to the incompatibility of collective memorialization, then, proves simultaneously his film’s highlight and crucial failing. Wielded like a cudgel against the beast of biographical precision and factual bookkeeping, Sosa’s dissolution of familiar outlines sees Liborio’s miracle-making reduced to peripheral expressions of wonder and validation across his disciples’ faces, his performances displayed with a surprising ambiguity that could, in certain quarters, be taken as heretical.

While not opposed to soaking in the spiritual enrichment and ecstasy that serve as meaningful ends to Liborio’s practice, this technique stands at odds with the film’s initial enigmas and its positioning of the healer as a talisman to all, conceived beyond reason and reproach; replaced instead with a filter of desultory normality. Since the man and his believers are outlined with an equally cursory attention to motivation, or interior deliberation, what emerges is a tangle of varying loyalties and innatisms whose differences are pronounced just enough to signify minor disunity, but vague and ultimately unimportant enough that the group’s eventual deracination renders them moot. Additionally, their undying adherence-to-the-cause, while never venturing into the textual ethos to contextualize it as paean, is cast-in from the get-go and frays noticeably with the above-mentioned refusal to depict Liborio’s newfound divinity as anything beyond imaginative construction. Amid the middle third’s tail-chasing accrual of everyday detail and communal gatherings — a curious, anthropological tack that’s organic flow is again interrupted by the respective subjectivities to which these observations are frequently tied back to — moments of personal rupture do occur. An energetic folk dance, which frees long-stifled emotions and doubts and ends in a violent confrontation, peeling Liborio’s unflappable demeanor several layers back, allows divisions previously observed to follow their natural conclusions off the beaten path and evinces a narrative filling at odds with prior determination. The commune’s sublimation into individual thought and deed with its leader’s brutal death at the hands of the occupying force only brings to light the lack of matching delineation between its members here; they can hence only be assumed as an undistinguished mass wherein perceptions, interpretations, and inclinations yield to a standard consensus that retreats to the established toolkit of history-writing.

Writer: Nicholas Yap