One of the great madcap poets of the American cinema, Alan Rudolph has seemingly slipped into irrelevance since his heyday in the 1980s and ’90s. If he’s mentioned at all in contemporary discourse, it’s usually to acknowledge his apprenticeship (of a sort) with Robert Altman, or the handful of his films that garnered awards consideration at film festivals (Altman has never been nominated for a writing or directing Oscar). Considered an “actor’s director,” Rudolph worked repeatedly with the same stable of performers, musicians, and technicians for long periods of time, and as the likes of Geneviève Bujold and Keith Carradine became less fashionable, so too it seems that Rudolph followed suit. It’s not exactly a case of “they don’t make ‘em like they used to” — no one seems to have really known what to make of him back then, either. An idiosyncratic iconoclast, blending and bending genres and various aesthetic modes to his own ends, Rudolph exists on a continuum alongside Rivette and even Leos Carax as a purveyor of playful, sometimes sinister cinematic games, directors that see modernity not as a repudiation but as an extension of old forms and outmoded gestures — silent film grammar, surrealism, the Hollywood musical, and noirs all coexisting together.

Following his (recognized) debut feature, the wildly erratic and expansive Welcome to L.A., Rudolph narrowed his focus to a smaller kind of film, an off-kilter thriller that forgets to include any of the elements traditionally associated with thrillers. Produced by Altman, with original songs by Alberta Hunter and cinematography by the great Tak Fujimoto, Remember My Name begins with the camera inside a car as it travels winding roads through rocky terrain, the jazzy title tune playing over the opening credits. Here’s Rudolph inviting us on a journey, destination unknown. Instead, it’s a kind of narrative game, teasing out elusive threads and really relishing the kind of connective tissue that’s usually skipped over by more story-oriented directors. Rudolph wants to wade into those in-between moments, where characters are at work or making small talk and bumping up against each other in discrete encounters that tend to reveal personalities through action and gestures more than dialogue (typically, dialogue in a Rudolph picture is interesting only inasmuch as it relishes in poetic flourishes and elusive figures of speech).

As the credits end, construction worker Neil Curry (Anthony Perkins) arrives on a job site, trading barbs with coworkers and getting his morning coffee. Elsewhere, his wife Barbara (Berry Berenson) arrives at home to a ringing phone. She answers it, but there’s only silence on the other end. There’s a cut, and Emily (Geraldine Chaplin) is revealed as the person making the call. She hangs up without saying anything and then walks past a sign that reads “brand new image” before entering a store looking for clothes. She stares at a mannequin, her eyes lingering over lingerie and a pair of handcuffs, speaks about pleasing an unseen husband, then takes her new items and rents a dilapidated apartment in a rundown part of town. It’s a curious sequence, which only snaps into place later as her motivations are finally explicated more clearly. As will be shortly revealed, Neil and Emily are navigating a rough patch in their marriage, while Emily is an ex-con and Neil’s ex-wife who’s been released from prison after 12 years. She continues to make phone calls to Neil and Barbara’s house, at first saying nothing, but gradually escalating things into general harassment, before finally confronting Barbara and Neil in separate encounters. These scenes take on the patina of a horror film, as Emily seems just unhinged enough to do something violent or otherwise drastic, but Rudolph tends to undercut the tension with moments of levity. Chaplin is remarkable in the lead role, her unique energy finally given a chance to fully command the screen after smaller roles in a few Altman films (she is, of course, also fantastic in Rivette’s Noroit, although American audiences wouldn’t have been able to see it by 1978). Filmmaker Ryland Walker Knight calls her “a force of nature more than a character,” and that the film is “a kind of fable despite looking like realism.” He’s right, and that alchemy is what makes Rudolph so unpredictable and exciting.

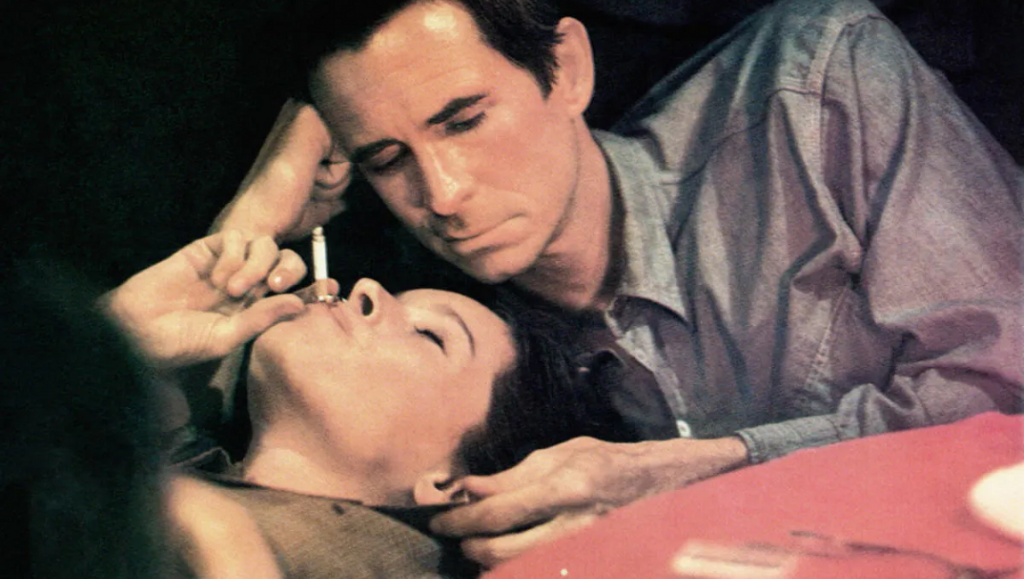

Once it’s been revealed that Emily has been in prison, Chaplin’s awkward personality makes more sense, as does her tendency to repeat words to herself or rehearse sentences before speaking to a person. She’s practicing normalcy, like an alien studying humanity who can’t quite get the cadence correct. Rudolph’s camera also starts finding ways to enclose Chaplin in the frame, with windows and doorways becoming visual corollaries to prison bars. Rudolph fleshes out this minimal plot with all manner of colorful supporting characters, creating a cross-section of types that are all trapped in one way or another. There’s a grocery store where Emily finds work, run by a young Jeff Goldblum, as well as Pike (the great Moses Gunn), a security guard who also acts as a kind of super at Emily’s building. There’s an odd, tentative romance between him and Emily, a few lovely moments that are discarded (painfully for Pike) when Emily decides for whatever reason that she must have Neil. Like all of Rudolph’s best films then, Remember My Name becomes about the search for love, that mysterious and often elusive emotion that Rudolph seems to both cherish and find terror in. Eventually, Neil does leave Barbara to return to Emily, even while recognizing that it’s a bad idea. But after sleeping together, Emily leaves Neil to take off on the road again, and the film ends on Barbara changing all the locks on the home she used to share with Neil. It’s a bittersweet finale, as one coupling ends with acrimony and another dissolves back into nothingness, but the image of Emily triumphantly driving away with a new wardrobe is also liberating. No less a luminary than Luc Moullet called Rudolph “an exemplary filmmaker, who is the only one in Hollywood that takes risks” — if only there were more like him still around.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.