Questlove’s debut film as a director is a success, defined as much by its outrage as its joy.

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, drummer of the legendary hip-hop band the Roots, besides his many other talents, is a music historian and professional DJ. Thompson deftly puts both of these skills to work in his debut feature, the alternately exhilarating and infuriating documentary Summer of Soul (… Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), which compellingly excavates the long hidden and nearly forgotten story of the Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of free concerts held over six weekends in the summer of 1969 in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park (now named Marcus Garvey Park). The concerts were attended by about 300,000 people and featured an insanely impressive lineup of acts: Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Nina Simone, the Staples Singers, David Ruffin, B.B. King, the Fifth Dimension, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, Mahalia Jackson, and Max Roach, among many others.

Summer of Soul is, in part, a tale of two monumental cultural events. At around the same time the Harlem Cultural Festival was happening, the Woodstock festival — which we should remember featured precious few Black performers — was being held a few hundred miles upstate. While Woodstock has been endlessly celebrated and mythologized — and here’s where the infuriating bit comes in — the Harlem Cultural Festival has been almost completely neglected in memory, its beautifully shot footage, by the late Hal Tulchin, sitting unseen in a basement for 50 years after he could find no buyers interested in turning his footage into a finished film. Tulchin, in equal parts savvy marketing and desperation, dubbed the event “the Black Woodstock,” but to no avail. In the words of one of the film’s subjects: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that Black history will be erased.”

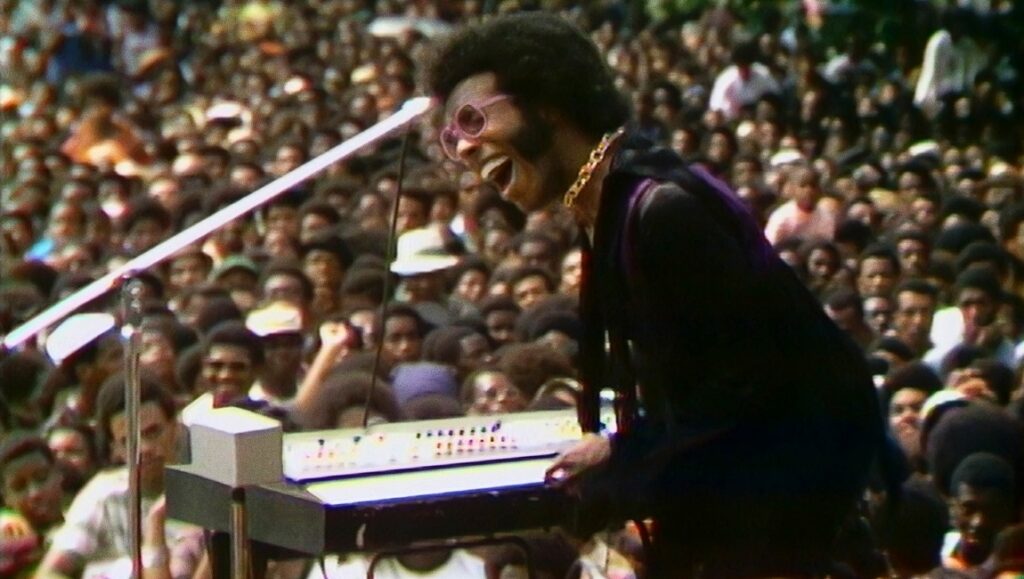

Thompson puts his skills as a DJ and musical curator to great use in Summer of Soul, his unerring instinct successful at finding resonant moments from the concerts. One example is an early scene in which a boundlessly energetic Stevie Wonder — then just 19, only a few years away from beginning his incredible run of ’70s album masterpieces — pounds out a funky riff on his keyboard and then steps behind the drum kit for a jaw-dropping display. Another scene that will absolutely delivers the chills is Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples teaming up to deliver a fiery yet delicately tender rendition of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” reportedly Martin Luther King, Jr.’s favorite song, one he requested right before he was assassinated.

Thompson, for this part, expertly weaves in reminiscences among the concert clips, capturing the words of both performers and attendees, while also ably explicating the turbulent sociopolitical context surrounding the concert, which coincided with a major shift in Black people’s consciousness at the time and reflected more radical politics coming to the fore. To paraphrase one of the film’s interviewees, this was the period during which the Negro died and Black was born. In a scene near the film’s conclusion, Nina Simone, while reading a poem, asks from the stage, “Are you ready, Black people?” After viewing this powerful film, one defined both by its outrage and its joy, the only logical answer, and not just from Black people, is a resounding yes.

You can stream Ahmir Thompson’s Summer of Soul on Hulu beginning on July 2.

Originally published as part of Sundance Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 7.

Comments are closed.