Parallel Mothers

If Pedro Almodóvar’s pandemic short The Human Voice hinted at a freshly energized director liberated from the burden of expectations, then his latest feature crystallizes this as fact. His first feature since the success of Pain & Glory finds Almodóvar in peak form, delivering a work of intertwining narrative and thematic complexity that echoes the sophisticated rhythms of All About My Mother, albeit with a tighter script tinged with political resonance. At first glance, Parallel Mothers may appear par for the course, after all, it sits so firmly in his dramatic wheelhouse, a melodrama centered on women, friendship, and motherhood, featuring some familiar faces (Rossy de Palma’s emergence drew joyous cheers at my screening). This go-around, however, the precision of craft combined with a confident sense of restraint gives the culminating drama a refreshing degree of weight and poignancy. Reinforcing this is an explicitly political thrust, one unusual for a director whose films so often confronted politics by irreverently broaching taboo. What makes this directness so effective is watching an idea set up in the first ten minutes quietly thread its way through the melodrama, only to resurface with full clarity, for a closing knockout punch.

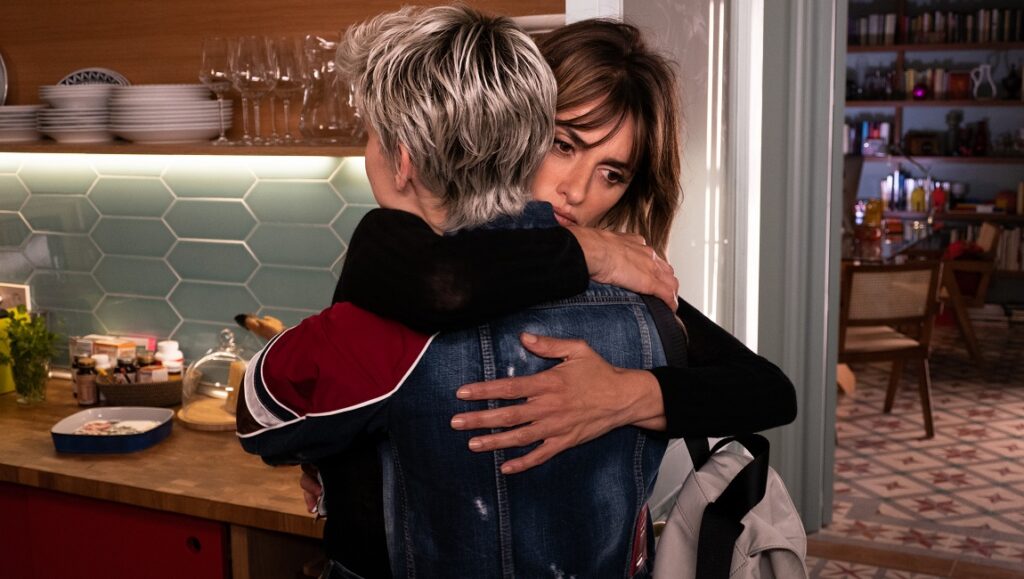

The center of the story is two mothers-to-be, Janis (Penélope Cruz) and Ana (Milena Smit), who bond in the maternity ward. The dynamics of this inter-generational relationship — Janis becomes a surrogate to Ana, whose mother is an absent and aloof actress — harken back to the friendship at the heart of All About My Mother wherein Cruz had once played the role of the young pregnant woman seeking comfort and support from Cecilia Roth. Twenty years later, Parallel Mothers reverses the dynamic, letting Cruz play the older more confident of the two, and in her own way pass the torch to relative newcomer Milena Smit. But while their relationship forms the meat of the story, the aforementioned bookends concern Janis’s quest to exhume the body of her great-grandfather (murdered in the Spanish Civil War), and gradually inform and empower with thematic thrust. Her cause mirrors a decades-long political struggle over the remains of the victims of the war buried in mass graves with over 110,000 still classed missing. The left-wing pushes for exhuming and identifying the buried as an act of healing, while the right-wing, reluctant to confront the past, urges against “reopening old wounds.” This tension is aptly paralleled within the two mothers: Janis takes pride in her familial roots, her apartment filled with photographs of her relations and history, while Ana resists confronting the trauma of her past encapsulated in the mystery of her baby’s father, yearning for a clean slate.

For Almodóvar, the past assails the present, and so he expertly cuts in between timeframes to grant us a richer understanding of Janis, whose elusive interiority Cruz captures with remarkable grace. Meanwhile, playful variants of his kaleidoscopic color schemes populate the frames, and everything from the wardrobes of the women down to their phone cases exist in delicate conversation as time flows backward and forward; the patterns of Ana’s favorite jacket reappear in Janis’s sweater dress after the two have moved in, and so forth. As the story develops, trailing down a series of twists and turns that test Janis’s resolve in her principles, the melodrama elevates into a rich portrait of pain, a mirror to the traumas of history that quietly lurk in the undercurrent. Almodóvar handles the shifting emotional terrain according to his trademark approach, affording sensitivity, empathy, and depth to his conflicted characters, ensuring that twists that may in less adept hands feel soapy or cheap carry the texture and gravity of realism. Of course, this measured control doesn’t preclude moments of pointed exuberance; a sex scene punctuated with Janis Joplin’s “Summertime” — her throaty croon swelling into the screech of a guitar solo — is a particularly inspired one.

What’s so impressive about Parallel Mothers, and Almodóvar’s oeuvre in general, is his capacity to wrangle the controlled chaos of his narratives into coherent wholes, even as they bristle against conventional structures. When we circle back to Janis’s mission to unearth her great-grandfather’s grave, the entire messy throughline compacts under the weight of a single culminating image. The stark return to the wounds of the Spanish Civil War is jarring and might catch some off guard, but it serves as a powerful rosetta stone for the preluding melodramas of the film. A story of two women grasping for and exhuming the pain of the past, while boldly pushing forward together. At the Q&A which followed the film’s NYFF premiere, Cruz revealed that Almodóvar approached her with a rough outline of the film during the press tour of All About My Mother over twenty years ago, and in fact, you can even find its title snaking its way into Broken Embraces as one of Harry Caine’s scripts. It’s quite something to consider how this story, itself a tether to the past, sat simmering on the back-burner for years until Almodóvar felt he could do it justice. The timing feels as ripe as ever, as earlier this spring, just as filming was getting underway, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez initiated plans to exhume and identify the bodies at rest in the Valley of the Fallen, a mass grave of more than 33,000 victims of the war. A moment which marks the beginning, not the end, of a process of reckoning with the past, a moment of both immeasurable pain and relief; Almodóvar seizes on it in the film’s startling final frame, as if to say: there in the open wound of the grave, our histories still throb.

Writer: Igor Fishman

C’mon C’mon

Next only to dead wives, doomed love triangles, abusive parents, and being “the chosen one,” precocious, quirky children might be the single most annoying and commonly relied-on narrative cliche commercial cinema has to offer. They’re usually paired with a grumpy adult for any given number of contrived reasons — one who may at one point openly verbalize their dislike of youngsters, depending on how hacky the screenplay is — where, upon spending a little forced quality time together, surprise surprise, each party learns a little something about life and themselves along the way, with a key emphasis placed on the curmudgeon’s outward nastiness being sanded down via the feels. Mike Mills’ C’mon C’mon is yet another rendition of this tired premise, though this one doesn’t even really try to construct much internal drama within its scenario. If anything, it largely plays like a “cute” story one parent would tell that absolutely nobody else in the office gives a shit about/has the courage to outright tell them to shut up about. Radio journalist Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix), a generally nice enough guy, volunteers to look after his estranged sister’s son Jesse (Woody Norman), who blasts Wagner in his free time and enjoys role-playing as an orphan — ya know, the type of kid who could only feasibly exist in works of pure fiction, usually written by people who’ve never actually raised one — where the two end up embarking on a cross-country journey of self-discovery, heartbreak, and blah, blah; you get the basic hackneyed idea.

Triteness, here, is Mills go-to engagement strategy with the material, as you don’t get one, but two different moments where Johnny loses Jesse in a public setting — all for them to kiss and make-up one scene later, possibly for fear of repelling viewers with the uncomfortable truth that child-rearing isn’t a pleasant experience — which is just one of many predictable, often calculated emotional beats and tactics in a film that feels like an extended list of them (including the use of bland digital black-and-white photography that’s clearly aiming for some Manhattan-esque poeticism). To counterbalance these blatantly deliberate narrative and formal strategies, there’s a rather laborious framing device thrown in involving real-life minors being interviewed about their futures, all for a documentary Johnny is working on; in practical terms, it’s the central reason why he and Jesse traverse across most of the United States for a bulk of the runtime. And while there’s an evident charm to seeing, say, Detroit adolescents rebuking popular media narratives about their hometown being some crime-infested hellhole, it plays like a last-ditch effort at inserting authenticity into a project that’s decidedly lacking in any, where the actual issues of today’s youth feel entirely disconnected from the supposed struggles presented here.

Writer: Paul Attard

Jane par Charlotte

Released in 1988, Jane B. par Agnés V. stands as both a major work in the filmography of Agnés Varda and one of the rare essential instances of cinematic celebrity biography. Varda’s film positions the British star/model/actress/singer as both subject and active collaborator with the two using playful, unconventional interview and acting exercise to articulate Birkin’s story and character, avoiding rote, literal-minded explanation. Jane B. par Agnés V. was conceived as a celebration of Birkin as she entered her 40th year on the planet, and now, as she approaches 75, daughter Charlotte Gainsbourg (who just celebrated her 50th birthday) picks up where Varda left off with a new documentary portrait of her mother entitled Jane par Charlotte. Or at least, that’s the idea in theory, but Gainsbourg (making her directorial debut) isn’t really interested in continuing the late Varda’s project beyond the allusion of her title and the basic premise of following Birkin around with a camera.

Jane par Charlotte adopts a very loose structure built around a world concert tour that Birkin was in the midst of pre-pandemic, Gainsbourg’s film initially focusing on her mother’s international celebrity and persistent artistry, before veering into more generalized, slice-of-life content in response to COVID travel restrictions. As Gainsbourg attests to in opening voiceover, this project presents an opportunity for mother and daughter to approach each other as they are unable to in everyday life, the tension between director/subject (and audience) bringing with it a potential to disrupt the rules and boundaries of their dynamic. Alas, not only does Gainsbourg end up ignoring the precedent set by Varda, but she fails to really rise to her own ideals here, never locating a particularly interesting angle from which to address her mother. Which isn’t to say that Jane par Charlotte doesn’t manage some candid moments, especially when it comes to getting Birkin to discuss her fraught relationship with her appearance as she’s aged and the persistent reminders of mortality that pursue her at 74. Death hangs over much of Jane par Charlotte, the fathers of 2 of Birkin’s children having now passed on (first husband John Barry and Charlotte’s father Serge), as well as daughter Kate Barry who left us in 2014, but its Varda’s absence that is felt most here, the film bearing none of her whimsy or imagination. Languidly paced and basically shapeless (a hasty voiceover at the end wraps the film up on a graceless note), Jane par Charlotte appears to have been a therapeutic exercise for this mother-daughter duo, but not so engaging for the rest of us.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Chameleon Street

In a late scene in Chameleon Street, Wendell B. Harris, Jr.’s 1990 film, an astonishingly brilliant and wickedly comedic interrogation of American racism’s corrosive effects on those forced to navigate its nearly impossible psychic and societal demands, the film’s protagonist and antihero Douglas Street (played by writer/director Harris) is being harangued by his daughter, who wants him to buy her new toys. In response, Douglas grabs a doll, sprays it with black paint, and tosses it at his daughter, saying, “There. New toy. Black Barbie.” In another scene occurring much earlier in the film, Douglas and his wife are out having dinner when they are accosted by a drunk white racist, who calls Douglas a “porch monkey” and proposes buying his wife’s sexual favors. Douglas stands up to this racist, criticizing him for his poor usage of the word “fuck” and proceeding to lecture him on the etymology of the word and the proper ways to employ it. Douglas gets punched in the face and knocked unconscious for his efforts to educate this man, but he has successfully demonstrated his intellectual superiority to his antagonist.

These two scenes are indicative of Harris’ absurdist approach to his subject matter, positing racism as a sick, cruel joke on its victims, who must come up with ever more wily and extreme ways to counteract and survive it. Harris based his film on the exploits of the real-life Douglas Street, a con man he’d read about in a newspaper article years earlier. The film depicts Street’s successive impersonations and con games he perpetrates on others; in a voiceover that intermittently pops up throughout the film, Douglas expresses his personal philosophy: “I scam, therefore I am.” He poses as a freelance journalist, a doctor, a graduate student, and a lawyer before he is finally caught and jailed, turned in to the police by his own wife.

Harris’ complex and mesmerizing work achieves its effects through intricately executed metafictional layers: it’s a film by an actor-director that’s largely about performance, inspired by Ralph Ellison’s classic novel Invisible Man as well as W. E. B. Du Bois’ writings about the double consciousness that Black people must often possess to survive in America, hiding their true selves behind a façade more acceptable to the larger white society, much of which harbors negative attitudes and stereotypes about Black people. To this end, Harris pointedly employs a burlesque comedy approach, resulting in an unclassifiable film that shapeshifts almost scene by scene. Much of the comedy derives from the way Douglas Street grasps the big picture of his con games, but gets tripped up by small details. For example, his act of falsely posing as a Time magazine journalist is exposed when someone notices that in his editorial pitch letter, he misspells the word “write” as “wright.” Other times, the comedy travels into queasy and disturbing territory; in one particularly stomach-churning scene, Douglas, while posing as a doctor, actually operates on a patient, cutting open a woman with no training or experience, getting his information from a medical reference book he consults beforehand in the bathroom. Astonishingly, the operation is successful; in real life, Street reportedly performed 36 hysterectomies before he was caught.

Chameleon Street won the Grand Jury prize at the 1990 Sundance film festival; this award has helped to launch many successful careers, for example Steven Soderbergh with his win just the year before for sex, lies, and videotape. Unfortunately, the win didn’t do the same for Harris, whose film, despite its considerable critical acclaim, got just a small, barely-there release in 1991, and was basically forgotten afterward. To date, Chameleon Street is Harris’ only completed feature film, though he’s spent many years trying to get follow-up projects off the ground. In fact, Harris believes that Chameleon Street was not just rejected by movie studios, but actively suppressed. In his interviews — which are often as fascinating as the film they discuss — Harris cites the fact that Warner Brothers paid $250,000 for the rights to remake it with more bankable actors, such as Will Smith and Wesley Snipes, but refused to release the original film.

But as they say, better late than never. Arbelos Films has now made available a 4K restoration of Chameleon Street, and will finally give this film — which still feels ahead of its time a full 30 years later — the proper release it so richly deserves. We can now celebrate the occasion of this great film’s belated rediscovery, as well as mourn the fruitful career that could have been for its immensely talented director.

Writer: Christopher Bourne

Comments are closed.