Poppy Field carries the veneer of importance but isn’t much more than a series of lazy ironies, a shallow character study in need of a character.

Over the past 15 years, Romania has firmly staked its claim on the international film scene, with such bold, acclaimed features as 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Police, Adjective, and, most recently, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn breaking through to enthusiastic American and international audiences. Indeed, these films that have found most purchase on the international scene have typically arrived under the Romanian New Wave umbrella, a cinema that emphasizes realism and favors methodical pacing, complex long takes, and jittery handheld. At this point, it’s enough that it seems fair to assume that the majority of Western filmgoers not specifically dialed into the European film scene might firmly believe every Romanian film to look and sound alike, interchangeable facsimiles that reek of high art, the direct result of film buyers and distributors simply cherry-picking what has worked in the past. And in fact, it’s fast reaching the point where it would be difficult to tell the difference between yet another prestige Romanian drama and a parody of one, a line which the latest import, the gay drama Poppy Field, comes dangerously close to crossing more than a few times.

All of the hallmarks of modern Romanian cinema are present and accounted for, but leveraged to shallow ends, and absent are the complexities and trenchant political and cultural commentary that mark the country’s best works. Poppy Field, by contrast, feels like a relic from another era, one where its story of a closeted gay man struggling with his sexuality would be considered novel. It would help the film immensely if its central protagonist wasn’t an unmitigated asshole whose selfish behavior alienates the majority of the characters onscreen, and likely viewers themselves. We are first introduced to the curt and buttoned-up Cristi (Conrad Mericoffer) as he welcomes a visiting friend, Hadi (Radouan Leflahi), who has traveled to Bucharest from Paris. On the city’s bustling streets, Cristi rebuffs any of Hadi’s attempts at affection, but that abruptly changes when the two enter the confines of an elevator and begin a hot-and-heavy make-out session. It doesn’t take much to deduce that Cristi is closeted, the reasons of why presented in quick succession, as Cristi’s sister makes a surprise appearance to check out her brother’s “gay phase,” while Cristi’s job is revealed to be that of a police officer. You see, police officers are cultural icons of staunch masculinity, and director Eugen Jebeleanu really leans into the irony that Cristi is both gay and a gendarme, as cops are referred to in Romania. Poppy Field exists in a world where not only is this dichotomy presented as somehow immensely shocking, but also one where The Village People apparently never existed. Cristi and his fellow officers are soon called to a local movie theater, where a group of ultranationalists has interrupted a showing of a local queer film to decry the insidious agenda of the homosexual, using religious iconography to support their cause. In a fit of rage, Cristi beats one of the gay filmgoers, a former boyfriend who threatened to out the gendarme for his seeming hypocrisy.

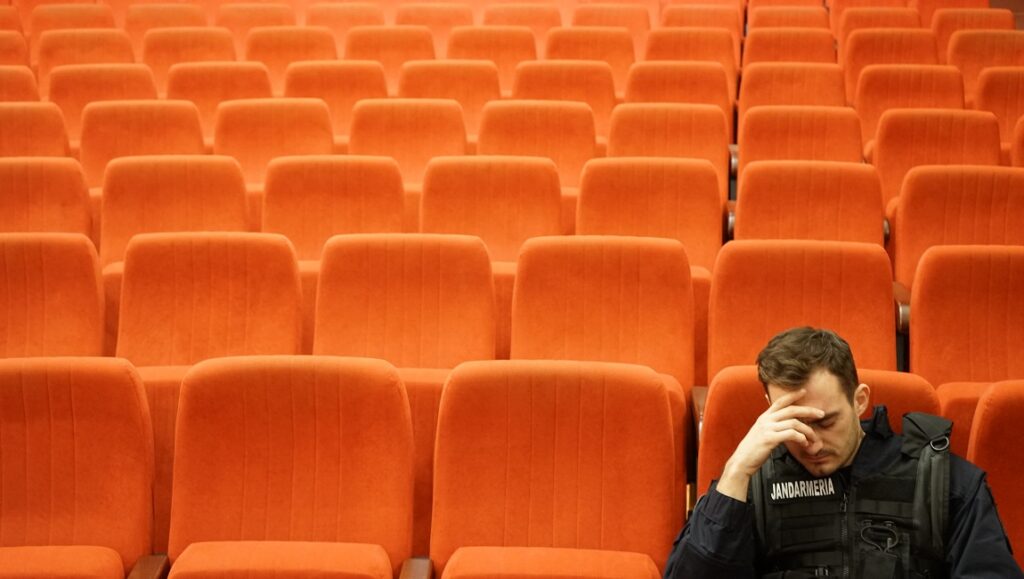

And so, the majority of Poppy Field takes place inside the now empty theater auditorium, as a frazzled Cristi contemplates his actions, occasionally interrupted by co-workers who tell stories about disease-ridden stray dogs, the likes of which may or may not be metaphorical. With the events currently taking place in Florida and the hateful cries of, “Don’t say gay” filling the airwaves, Poppy Field is certainly timely, proving that both America and the world at large have a long way to go when it comes to a loving, inclusive treatment of the LGBTQ+ community. Unfortunately, the Boys in Blue are also having a bit of a moment themselves, and that this film asks viewers to feel sympathy for a police officer who beats an innocent citizen is a pretty impossible hurdle to overcome, especially once intimations are made that this isn’t the first such incident with this individual. Perhaps a meaningful study could still have been made, ill-conception aside, had Cristi been gifted any sort of dimension, but he’s nothing more than a straw man on whom Jebeleanu and writer Ioana Moraru can foist their lazy and antiquated ironies. To even call this a character study, which is what the film so desperately aspires to, would be a stretch, as it implies there is an actual character to be located in this miasma of schlock. Poppy Field is the type of movie that carries the veneer of importance but has no interest in getting its hands dirty in any meaningful way. As is the case with its protagonist, no lesson is learned by film’s end, nothing of value gained — this is merely another portrait of a closeted macho asshole being a closeted macho asshole. Perhaps their story has been told enough.

Comments are closed.