It’s 1995, halfway through the decade and two years into the centrist liberal Elysian era of pre-blow-job Bill Clinton, a year in which Forrest Gump cozened millions with its reactionary sentimentality and Yahoo became Incorporated and the House of Representatives voted to cut taxes on corporations. It was a year in which 168 people perished in an act of domestic terrorism, and a plumber pilfered a 57-ton tank and took the hulking killdozer for a joy ride around San Diego until the cops shot him dead, this during the same month OJ tried to squeeze his hand into a blood-soaked glove, Cal Ripken, Jr. became the Iron Man, and the Unabomber published his manifesto.

1995 was also the year, of course, of Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls, written by sleazoid scribe Joe Eszterhas. Professional film critics, those fraudulent experts, came to the embarrassing (and, for a long time, enduring) consensus that Verhoeven’s Showgirls is a bad film, and not just a bad film, but one of the worst ever. Their hyperbolic hostility bewailed the lack of likable characters; they were upset by all the wanton selfishness, by the absence of sentimentality and the unpleasant acknowledgement that, in America, success is often achieved through iniquity, and that greed is as infectious as a venereal disease — all of this sardonic satire, not even particularly subtle, proved elusive. Most damningly, though, was that, despite all those naked women, the movie just wasn’t very sexy. How can you parade around a bunch of hot chicks and not even have the decency to turn the audience on? The abysmal box office performance and the vehemence of its many denigrators made Showgirls a hellacious failure. It isn’t surprising, though, that something so allegedly aberrant had an allure for a certain type of moviegoer — $100 million in VHS sales worth of it.

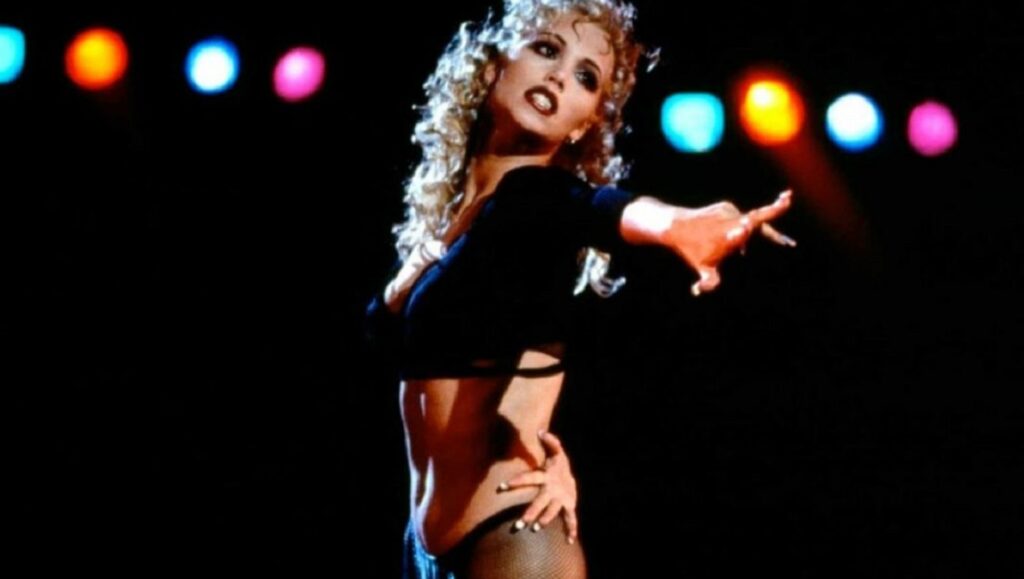

The film, damned with the designation of “camp,” quickly become one of those so-bad-it’s-good things, a sentiment that belies Verhoeven’s formal felicity — the bold colors and voluptuous camera work, the vivacious movement of the choreography recalling classic Hollywood musicals, the way faces gleam in the harsh showtime lights. In a scene near the end of the film, Verhoeven rejects a classic “rule” regarding the camera crossing the 180-degree line during a shot/reverse-shot scene, a decision most interpreted as a mistake, as incompetence; it is not a mistake, but the tenet of a mad Dutchman. He knows exactly what he’s doing, breaking a rule to show the switching of power from the old guard to the new, and it’s a terribly bad-faith criticism to say the guy behind something as seethingly sardonic as Robocop or bat-shit crazy as The Fourth Man doesn’t know what he’s doing. Verhoeven has an exquisite understanding of space and timing. Notice in the first dance section how each shot, each cut, flows together so we always know where the dancers are and what they’re doing, as tufts of fire rise behind them and everyone is bathed in red and yellow.

I spoke with Verhoeven a few years ago for a now-defunct newspaper, and he said, emphatically, leaning out of his seat, the septuagenarian like a child riled up, that Showgirls was the film whose failure hurt him most. “They just didn’t get it,” he said of the critics. “But the fans understood. That’s why it did so well on video.” He has a vivacious spirit, white wisps of hair protruding every which way, his wiry wrinkled limbs gesturing here and there as he leapt to his feet and used one extended arm to imitate the scene of a train speeding into a darkened tunnel at the end of Hitchcock’s North By Northwest, repeatedly stabbing the air and retracting, growing more excited each time. “It’s about sex,” he pointed out. “All movies are about sex.” In, out, in, out. It’s this playful, exuberant Verhoeven that you see in his best movies; think of the acerbic commercials littered through Robocop (“I’d buy that for a dollar!”), or the news clips (“Would You Like To Know More?”) in Starship Troopers, one of Verhoeven’s personal favorites, or the joke about pronouncing “Versace” in Showgirls.

It’s this playful dedication to entertainment that makes Showgirls Verhoeven’s lecherous opus. It’s a film that insouciantly ignores the popular trends of its era. It is committed to its tawdry convictions, unfaltering in its recalcitrant cynicism, and its soul, the throbbing heart that gives the film life, is Elizabeth Berkley, whose career never recovered. Not yet 25 and inextricably associated with her role as Jessie, the straight-A, socially conscious high school student on Saved By the Bell, Berkley wanted to exuviate her teenage TV actress image and establish herself as a serious performer. Casting the former teen star as Nomi (a role that was rejected by Charlize Theron, Angelina Jolie, Drew Barrymore, Pamela Anderson, and Denise Richards, among others) was partially stunt casting. At that point in her career, Berkley wasn’t a very “good” actress, at least not in the stagy Meryl Streep sense that looks so good in out-of-context clips and inveigles awards voters with volume and histrionics; but Berkley’s performance here, an innominate work of physicality and peccable self-realization, is one of the most daring to ever appear in a Hollywood film.

Nomi arrives in Vegas as a naïf , eyes twinkling with delusory dreams. Consider those early scenes when Nomi still clings to the leavings of innocence, and Berkeley’s mannerisms and line deliveries are tinctured with a sense of naïveté, a sense of desperation. It is hope, quivering, anxious hope, that keeps her going. But over time, the accretion of misfortunes erode her optimism and her innocence, her ignorance, molder away. “Life sucks. Shit happens.” Consider the scene in which Nomi, pole dancing in a sordid bar run by a real creep, has to give Zack (Kyle MacLachlan) a lap dance while Cristal (Gina Gershon), a vindictive, self-regarding dancer whose stardom may soon fade, watches and does bumps of blow; notice the faces in the scene —MacLachlan in tremoring elation, Berkley impersonal, and Gershon with the look of cruel satisfaction on her face slowly giving way to unuttered acrimony. Berkeley moves her lissome body with skill, unselfconscious, the salaciousness feeling vulnerable but not helpless. This is an erotic act performed for profit, not desire. The whole endeavor was supposed to embarrass Nomi, make her feel cheap, just something to be purchased and discarded, but Nomi has begun to understand how to play “the game.” “Everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power,” Oscar Wilde said. Nomi understands this; she sees the power in sex, in craven carnality.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.