While his first directorial credit for a commercial project was released a decade after the Movie Brats first took hold of Hollywood in the late ’60s to early ’70s — where a mere year after 1978’s I Wanna Hold Your Hand, he would collaborate with Steven Spielberg on 1941 — Robert Zemeckis is, in heart and spirit, one of the last real movie-makers from that era and of that temperament who has continued to operate with the same level of showman-like enthusiasm that marked the beginning of his career. Like Lucas, De Palma, and Scorsese before him, Zemeckis went to film school — he was fascinated by his parent’s portable, 8mm film camera and watched copious amounts of television in his youth — but truly honed his craft by editing Chicago public access television before eventually transferring to USC (all after literally begging admissions to let him in despite his unimpressive GPA). As he put it, he didn’t get a B.F.A. in Film because he was interested in replicating the French New Wave; he got one because of his interest in Clint Eastwood, James Bond, and Walt Disney. Truly, if one were to imagine a Venn diagram based on those three entities, it’s easy to argue that Zemeckis would sit directly in the middle of the intersection: he boasts the cultural prowess of the Disney monolith, the adventurous nature of Ian Fleming’s beloved spy, and the artistic ambition (and late-period idiosyncrasies) of Eastwood.

The first major leg of Zemeckis’ career — from his debut feature up until Forrest Gump — is comprised of mostly lighthearted titles with populist sensibilities, all of which heavily lean into a somewhat cherry cynicism that could be mistaken for gross eye-winking. Used Cars, Zemmicks’ second feature, takes its central premise (a used car salesman really is the lowest scum on the Earth) to the most extreme of comic ends, one that neither celebrates nor condemns the revelry that ensues. During a graphic, feverish mid-section set piece where Kurt Russel’s ever-slimy Rudy Russo attempts to get a free ad spot during a primetime news broadcast, his partner (a hilariously delirious Gerrit Graham) accidentally rips one of their model’s dresses off on camera. The resulting pandemonium is traced with several cuts across a litany of different suburban living rooms around the city, where the nuclear families proceed to watch the ensuing scene with their mouths agape, children and grandparents seen screaming at the absurd episode. Yet, nobody gets up to change the channel or to even turn the TV off (heaven forbid); in Zemeckis’ view of America, sex — and to a larger degree, pageantry in general — sells, and we’re all the happy consumers. Like the lowly merchants of his film, Zemeckis has a product he wants to sell and he wants to sell it to as many people as humanly possible.

More or less, this is also what eventually ends up happening with his Back to the Future series (with two sequels produced in response to the original’s popularity, not necessity), his first major work to be easily identifiable within the lexicon of popular American cinema, one that cemented Zemeckis’ reputation as H-Wood’s premier Blockbuster filmmaker of the time with its slick combination of narrative ingenuity, charismatic star power, and deft attention to detail. It was his first screenplay in five years — he didn’t write Romancing the Stone — and the only one he would write during that decade; instead, his interests seemed to turn toward special effects wizardry, building and improving upon his already solid abilities as a visual storyteller. This new fascination would first manifest in Who Framed Roger Rabbit as a bold formal gambit, one that could, again, be mistaken for a much cruder move: the non-stop inclusion of both live-action footage and animated sequences, seemingly existing side-by-side in harmony, was implemented with a sophisticated technical panache that wouldn’t allow for the illusion to be shattered. So on top of director, screenwriter, and producer, we can add the title of “movie magician” to the list of Zemeckis’ many honors; in 1997, he even rebranded his fledgling production company of South Side Amusement Company into ImageMovers to focus on CGI-animation and motion-capture technology for his future works.

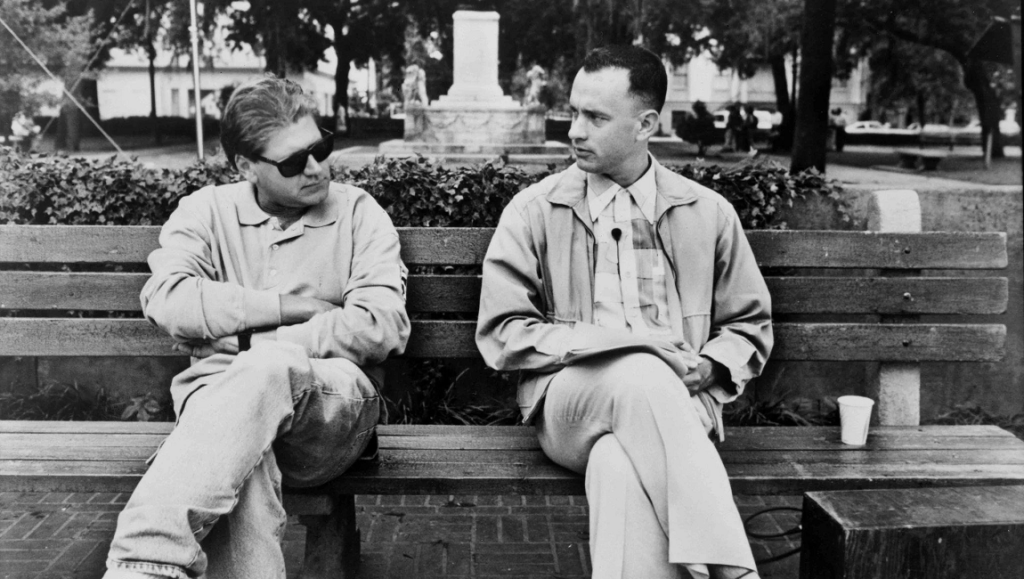

However, it was with Forrest Gump that Zemeckis truly entered into the realm of critical respectability… or did he really? Often mistaken for a piece of conservative propaganda made for baby boomers to remember The Good Ol’ Days, Gump’s staying power is directly tied to its egocentric view of not only history but the world at large: the pervasive and insidious idea that all the major national/world events in one’s life have a direct connection back to the source. Gump walks through the world oblivious, but we know all the better; the fact that so many film voices have refused to see the grand irony of it all says more about them than Gump itself. But the Academy loved it, showering the film with six Oscars, including a coveted Best Director award for Bobby Z. Steven Spielberg, rather fittingly, was the one to hand him the golden statue.

Since then — which one should recognize as a sort of mid-point for Zemeckis’ career, the halves of which we can characterize as either B.G. and A.G. (before and after Gump) — his filmography has moved in ebbs and flows, at least commercially speaking; some hits (Contact, Cast Away, The Polar Express), and a LOT of recent misses (A Christmas Carol, Allied, Welcome to Marwen), though the reputation of even these depends on who you’re talking to. But whatever it was that propelled his output in the wake of Gump (a bunch of failed attempts to reach the same level of cultural ubiquity, perhaps) hasn’t really provided the same creative force in the past decade or so. Instead, Zemeckis has turned inward with a series of personal projects that stress the importance of computer-generated imagery — Flight, The Walk, the aforementioned Allied and Welcome to Marwen — that display little regard for what contemporary audience members look for in mass entertainment. So painting Zemeckis as a cinematic ringmaster isn’t completely accurate, as it would imply that if nobody came, the show wouldn’t go on; for Bobby, he’d perform for an empty audience, no questions asked.

For the next few weeks at InRO, we’re going to take a look at the totality of Zemeckis’s entire filmic output, from I Want To Hold Your Hand to his upcoming Pinocchio, regardless of their classifications of “high” and “low” art, flop or box-office smash. Those constricting classifications clearly don’t exist for Zemeckis, so why should they for us? We’re more than happy just to sit and observe the long-winding career of the man of the hour, the master of cinematic ceremonies.

One piece per day will be published every day — Sundays included! — from August 21 until September 8, when Robert Zemeckis’ Pinocchio is set to be released. Individual pieces will be linked below as they are published, and this introductory essay will remain the hub of our Robert Zemeckis retrospective.

I Wanna Hold Your Hand / Used Cars / Romancing the Stone

Back to the Future Trilogy / Who Framed Roger Rabbit / Death Becomes Her

Forrest Gump / Contact / What Lies Beneath

Cast Away / Motion Capture Trilogy / Flight

Comments are closed.