In a crowded field of sci-fi adaptations, the buzzy TV treatments of Octavia Butler’s Kindred and Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven stand out. In Kindred, as adapted by showrunner and playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, a young woman named Dana (Mallori Johnson) and her boyfriend Kevin (Micah Stock), a white man, find themselves jerked back and forth between present-day Los Angeles and antebellum Maryland. Back in 1815, their survival hinges on pretending to be slave and master so Dana can covertly keep an eye on Rufus Weylin, a young white child from whom she’s descended. Meanwhile, in Station Eleven, an orphan named Kirsten is among a small handful of humans who’ve survived a global flu pandemic and attempt to rebuild society. These characters are trapped in situations unimaginable to modern audiences, yet approach their circumstances completely differently. For Kirsten and her friends, who’ve joined a traveling theater to salvage moments of joy from their grief and fear, “survival is insufficient.” If only the characters in Kindred could enjoy such an approach. Olivia (Sheria Irving), Dana’s mother who was sent back in time a decade ago — and chooses to stay behind — instead bluntly tells her daughter that “people here choose survival for its own sake.”

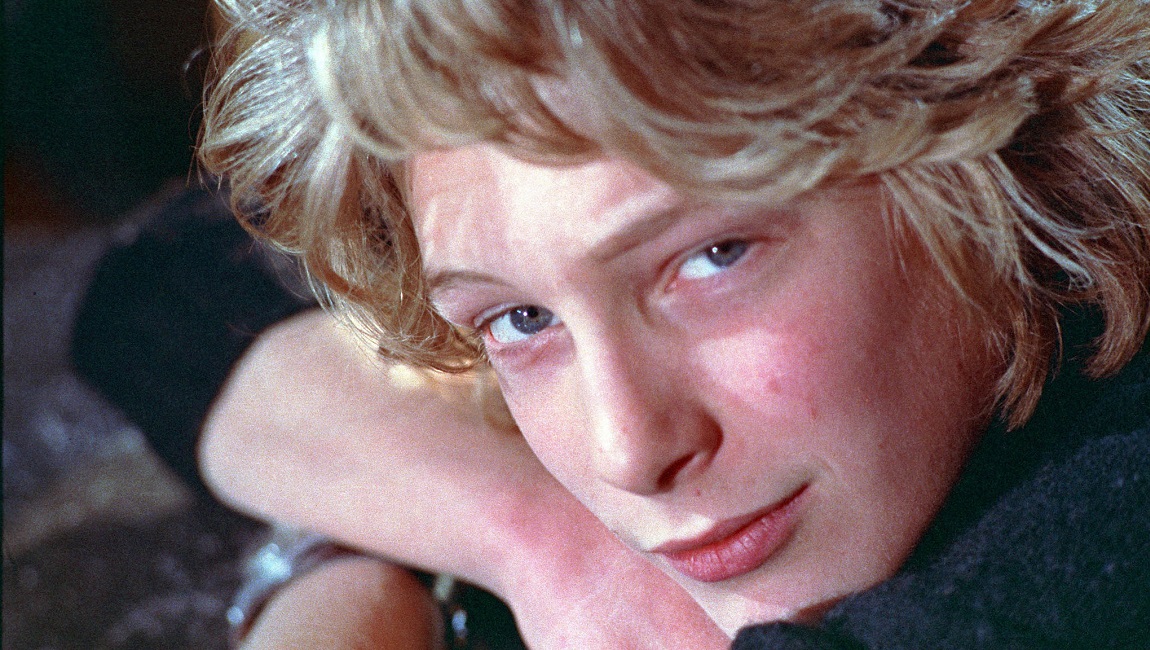

The second half of Kindred’s first season drives home the profound vulnerability that almost every major character faces when confronting institutional racism. Dana and Kevin walk an impossible tightrope of trying to subtly improve their surroundings and find a way back home without angering the Weylins and endangering themselves or the plantation’s slaves. At the same time, the slaves, including Luke (Austin Smith), Winnie (Amethyst Davis), and Sarah (Sophina Brown), are constantly on the verge of death by starvation, overwork, whippings, or childbirth — all while facing the threat of being sold somewhere even worse. Tom (Ryan Kwanten), the plantation’s tyrannical and hard-drinking owner, and his petty and insecure wife Margaret (Gayle Rankin), aren’t much more than caricatures of southern slaveholders — anything else and they’d risk being too sympathetic — but that doesn’t undermine their brutality. Instead, they embody the cruelty and paternalism that undergirds the entire institution of slavery, and their actions create an ever-more-powerful and self-justifying cycle of abuse. This confounding combination has repercussions that their slaves know all too well, and that Dana and Kevin must experience for themselves firsthand.

Having significantly expanded Butler’s source material with new characters and storylines, much of the first season focuses on world-building and interpersonal dynamics. However, instead of adding suspense or intriguing new themes, these creative liberties often feel unwieldy and forced. Most glaring is Jacobs-Jenkins’ decision to emphasize certain relationships and underdevelop others, perhaps in anticipation of a greenlight for season two. For example, Dana’s connection with Rufus is barely explored at all, despite being the primary cause of her time travel. Dana and Kevin as a unit — a married couple in the novel, but here just starting out together — is similarly sidelined. Most of these later episodes are structured along understandable but no less aggravating gender lines: Dana mostly deals with Olivia and the female slaves in the kitchens while Kevin is afforded opportunities to glean information and context cues from Tom. At the same time, both Dana and Kevin repeatedly make uncharacteristically careless mistakes that undermine not only their romance but their safety, such as being spotted together in the same bedroom or, even more damning, being caught teaching slaves how to read. These may be effective plot points, but perhaps not worth making at the expense of the characters’ — and audience’s — intelligence.

All of these factors can lead to frustratingly slow episodes that recycle the same minor points, as if wringing out tiny moments of humor from the cheerless situation (yes, Kevin is always underdressed by 19th-century standards). This sluggishness feels all the more unpleasant as we spend more and more time at the plantation, where the skewed power dynamics put characters and audiences alike at the Weylin’s mercy. Thankfully, Jacobs-Jenkins mostly avoids the pitfalls one would expect from his subject matter, making sparing use of the N-word and letting the everyday horrors of plantation life speak for itself. And Johnson, who was still an acting student at Julliard when she was cast as Dana, grounds the show with a nuanced portrayal of silent resolve and compassion. A thoroughly modern young woman who’s accustomed to total agency — in the pilot she sold her family home and moved across the country by herself — she’s now forbidden to even enter certain rooms in the Weylin house.

Kindred is perhaps most evocative in how it depicts the awful ways that slavery distorts and destroys human dynamics and relationships that could otherwise blossom organically. The slaves don’t trust Luke, a Black man who was once Tom’s childhood friend and now his slave driver, because he reports to the master. Tom and Jake (Karson Kern), his cruel overseer, take for granted Kevin’s sympathies because they’re all white men. Dana and Kevin have to hide not only their romantic relationship, but even their mutual respect. And finally, Dana and Olivia can never have a meaningful relationship because Olivia has resigned herself to enslavement and has chosen to move on from her past life. But just as Olivia decides to stay behind so she can take care of a young orphan girl (disregarding that Dana is essentially an orphan herself), Luke would rather stay at the plantation than leave the slaves with Jake. This is the flip side of slavery’s perverse breakdown of humanity: that even in the face of overwhelming danger and unimaginable cruelty, bonds can still be forged from the ashes.