River

Director Yamaguchi Junta’s Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes was a delightful no-budget time travel comedy that hit the scene a couple of years ago, delighting audiences with its audaciously simple premise — a man discovers his computer monitor is linked to another downstairs which displays events that will take place exactly two minutes into the future — built up nonetheless in ingenious ways, using only a handful of actors. Yamaguchi, once again united with writer Ueda Makoto (The Tatami Galaxy; Night is Short, Walk on Girl), returns this summer with River, yet another two-minute temporal anomaly, on an ever so slightly larger scale, but with equally delightful results.

This time, it’s a time loop film: workers and residents of a traditional Japanese hotel find that their world resets itself every two minutes. Unlike in Mondays, which played at this year’s Japan Cuts, or other time loop narratives — such as the Star Trek: The Next Generation episodes “Cause and Effect” or ”Time Squared,” the latter of which gave Orbital the essential sample, “There is the theory of the Möbius — a twist in the fabric of space, where time becomes a loop” — everyone is quite aware of what is happening right from the beginning. The drama, then, comes from watching the characters try to figure out what has caused the loop, and what they can do to fix it. Yamaguchi films every two-minute section in continuous takes, probably shot on a telephone or some similarly lo-fi digital camera, like the long takes in Beyond. A probable concession to the realities of low-budget filmmaking, but adding an especially surreal edge to the looping, is that the weather outside is always changing: about to snow in one scene, dry and sunny the next, snow covering the ground after that. Time isn’t just repeating — the residents of the hotel have become disconnected from the space around them as well.

Leading us through it all are the workers, as one by one they get together and try to reassure the patrons that what is happening is real and that they will find a solution eventually. This provides the film’s funniest moments, as these unflappable women explain to panicking vacationers how delightful it is to be stuck in a time loop (they can drink without getting a hangover, eat without gaining weight!), while wondering if they’ll get paid overtime for all these extra minutes they have to work. Our primary character is Mikoto, played with resolute charm by Fujitani Riko (one of the stars of Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes). It turns out that she has a crush on one of the kitchen staff, and, learning he plans to go away to Paris to learn the art of French cuisine, has made a hasty wish to the local river god to stop time. This is the first theory as to why the time loop started, and it gives everyone else the opportunity to blame — and then forgive — her, but also lends the young couple an opportunity to spend some precious time together to see what kind of relationship they could actually have (time that otherwise wouldn’t be possible given work requirements). The cause turns out to be something else entirely, which pads out River’s running time (a bit longer than Beyond’s 70 minutes), but also shows us how many people really do wish time could slow down or stop for a while. Though of course, when it actually does, their first instinct is to panic or fight or shoot themselves. Yamaguchi’s final product is exactly as kooky and homemade as it should be. — SEAN GILMAN

Mami Wata

In C.J. Obasi’s latest film, the small, relatively isolated village of Iyi is overseen by Mama Efe (Rita Edochie), the group’s intermediary who lives in tune with the power of the titular African water spirit, Mami Wata. Problems come when Mama Efe’s power begins to be questioned after a young boy cannot be cured and dies, and as tales are told about the progress undertaken by other nearby villages, with schools, hospitals and medicine, and other markers of so-called modernity. The opportunity is ripe for someone to bring about a dramatic change.

The dichotomy between modernity and tradition is a very common theme in African cinema, though it tends to be generalized — as the scholar Jude Akudinobi wrote recently: “The tradition/modernity formulation glosses over the categories and terms on which the discourse of contemporary African politics hinges. Not only is it mechanistic, it is patently simplistic and expressly misleading.” At its best, Mami Wata deliberately confronts this tendency, largely through the character of Prisca (Evelyne Ily Juhen), Mama Efe’s protégé who nevertheless is initially convinced by an outsider’s plan to overtake the village and introduce modernity to it.

Still, as Akudinobi warns, recent African cinema runs the risk of overplaying their theological and philosophical hands, as they “manifest the struggle to find a language to articulate the ideological tension generated by casting African cultural heritage as a dark shadow on modernity.” Of course, the outsider turns out to represent the violence of White patriarchal capitalism, never delivering on his promises of so-called progress, and so Prisca finds herself the only hope for the village to regain its identity and peace. In some sense, this plot development feels too predictable, and the actions of the characters can seem frustrating in these moments, as though they, too, cannot see past these longstanding cinematic tropes.

This is clarified somewhat as the film progresses, revealing an intimate awareness of the simple fact that these phenomena coexist in modern Africa, and that its people are routinely forced into competing claims over what an “African identity” is or can be. Mami Wata, in its folkloric structure and attunement to convergent futures, wants to dramatize this negotiation, what Akudinobi calls a “complex identificatory milieu.” It is a negation of the dichotomous, even if it doesn’t always succeed in conveying the simultaneity of that sort of lived reality.

The gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, combined with Juhen’s memorable performance as Prisca, work to underline the complexity of African representation today, so often, as here, tied to former colonial states and their funding agencies, and de facto treatises on African moral philosophy in the 21st century, whether or not by their choice. Prisca, then, capably shoulders the weight of this disjuncture, the core transitional nature of any society or people, embodied in a character pulled in more than only two directions, and instead toward endless paths of reconciling the individual and the collective. In other words, people are dynamic forces and change will come, and it will almost certainly be according to scripts as yet unwritten. — JAKE PITRE

Hundreds of Beavers

They say that comedy is subjective, but even that benign truism can’t begin to explicate the lunacy at the heart of Hundreds of Beavers. It’s mind-boggling that a couple of buddies got together and concocted this strange brew — a (mostly) silent, black-and-white-slapstick epic inspired by Looney Tunes cartoons and musicals, and consisting of more gags per minute than even ZAZ in their heyday. It’s a genuine oddity and a true labor of love, too; director/co-writer/editor Mike Cheslik and producer/co-writer/star Ryland Tews have been friends since high school, and their films (including 2018’s Lake Michigan Monster, in retrospect a dry run for much of the formal brio on display here ) seem to have emerged from a kind of shared psychosis. Beavers is composed of sharp, high-contrast digital black-and-white photography, Monty Python-esque cut-out animation, blue screen digital trickery, and all manner of post-production tinkering. The film’s press notes describe some of the efforts involved here, including 12 weeks of filming in Michigan and Minnesota in sub-zero temperatures, and four years (!) of off-and-on work on the various compositing effects. One is left staring slack-jawed at this singular, unique work, a testament to the blinkered, single-minded determination of two weirdos (with the help of a dedicated cast and crew, of course) who think that concocting different scenarios of killing beavers is really funny. It’s a miracle that they mostly pull it off.

It should come as no surprise that there’s not much of a plot to detail here; when a bunch of beavers destroy Jean Kayak’s (Tews) Applejack Cider brewery, he decides to begin hunting them. After falling in love with the local fur trader’s daughter, Kayak learns he must bring the man a hundred beavers to win the daughter’s hand in marriage. The rest of the movie constructs an escalating series of events as the novice trapper learns the ropes of his new trade, gradually leveling up from a know-nothing dunderhead to a God-like hunter of immense prowess. This process is detailed via a series of elaborately conceived and executed gags, a veritable avalanche of non-stop physical comedy that builds and builds until it reaches a crescendo the likes of which we’ve never seen (it involves beavers joining together to form a giant figurine, not unlike Voltron or a kaiju). Over the course of its (admittedly) exhausting 110-minute runtime, the filmmakers take The Simpsons‘ rake joke to new heights. Writ large, the film’s jokes go from funny to belabored and then back to funny, the filmmakers’ exhibiting a deft hand with well-timed smash cuts and elaborate montage. It’s a beautifully designed movie, too, occasionally resembling the graphic sensibility of Russian constructivism design and German Expressionism — a long sequence set inside the beavers’ headquarters even brings to mind Fritz Lang, of all things. Lest that sound too highfalutin, there are also lots of piss and shit jokes, and extended scenes of beavers being ripped apart and rent asunder — but don’t worry, the beavers are realized using human-sized costumes, the organs are plastic, and the blood is styrofoam packing peanuts. It’s obviously beyond ludicrous, but Cheslik and Tews are so committed to their absurdist vision that it all becomes endearing. Hundreds of Beavers is likely best experienced with a raucous crowd, alcohol and other intoxicants optional (but recommended). Come for the unique craft, stay for the strangely touching ending, as pure a distillation of Conrad’s ”hero’s journey” as you’ll ever find. It’s a sui generis experience, that’s for sure. — DANIEL GORMAN

Home Invasion

Allegedly an “experimental” video essay/documentary on the history of the doorbell, director Graeme Arnfield’s Home Invasion purports to be an unsettling and insightful exploration of how a seemingly innocuous invention has propelled generations of racism, classism, and paranoia. By and large, though, it undercuts an admittedly interesting thesis with some shoddy technique and unsourced anecdotes in place of actual data-driven conclusions.

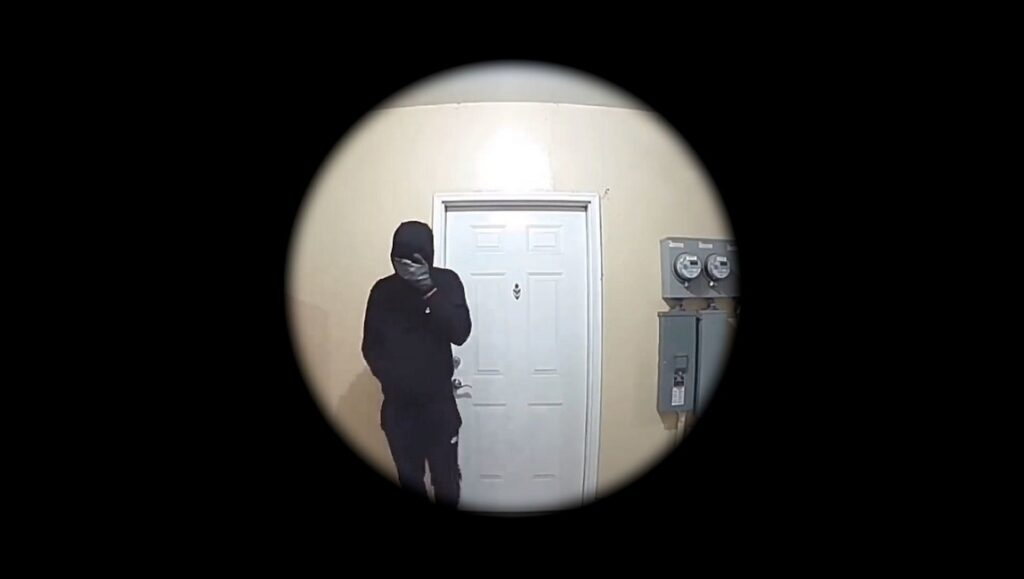

Part horror movie, part found-footage doc, most of Home Invasion is constructed out of onscreen text and endless doorbell/Ring cam footage. Beginning with the tale of Marie Van Brittain Brown, a nurse who in 1966 invented the first video-based home security system, the film then jumps ahead to the development of what would become Amazon’s Ring by a depressed Shark Tank reject, before cycling way back to the story of the Luddites (illustrated with woodcuts and contemporaneous 19th-century art, all inexplicably fish-eyed to look like the ubiquitous door-cam stuff). Along the way, there’s an investigation of the telephone’s influence on modern slasher movies, although there’s inexplicably no such discussion of video surveillance.

What you mostly have in Home Invasion, then, is that Ring footage; there are a lot of crummy delivery guys, confused DoorDash gig workers, and curious stray animals. Occasionally, there’s a spooky dude in a ski mask or drunk asshole or shitty ex spitting profanities and pounding on the front door, and the whole thing is slathered in scary music and covered in ominous onscreen text. Its arguments that corporate-sponsored home surveillance and connectivity have made us a generation of bigoted narcs are certainly tantalizing, but there’s no actual data here, and in fact not much more than a direct poke at the viewer’s emotions, as opposed to a more concrete and cogent examination of these unquestionably complicated dynamics. And although the thematic connections between all these various stories are fairly self-evident, they don’t really track narratively; there’s simply no momentum. One could very charitably compare the whole thing to the works of Adam Curtis, but Home Invasion doesn’t bear any of that director’s insight and ability to tie together seemingly disparate threads in illustration of a thesis. In dragging what seems primed to be a short video essay out to feature length, the whole undercooked project becomes a mere slog. — MATT LYNCH

Take Care of My Cat

One of Fantasia’s 2023 archival presentations is Jeong Jae-eun’s 2001 coming-of-age ensemble film Take Care of My Cat. The movie was a critical hit when it premiered in 2001, playing on the festival circuit at a time when Korean cinema was just beginning its international breakout. Though not a commercial hit at home, it did help launch star Bae Doona’s career, alongside her work for Bong Joon-ho in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Park Chan-wook in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Bae has since become one of the great stars of world cinema, with classic films in Japan (Linda Linda Linda, Air Doll), the U.S. (for the Wachowskis in Cloud Atlas, Sense8, and Jupiter Ascending), and at home (The Host, Chang-Ok’s Letter, A Girl at My Door, Broker). She leads the ensemble here — a group of five young women, friends from high school who, a year after graduation, find themselves growing apart as they have various troubles adapting to adult life. Each, in turn (although some more briefly than others), will be the caretaker for a small kitten, giving the film its title and the chance to be described, more or less misleadingly, as “Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, but where the pants are a cat.”

Bae plays Tae-hee, who has spent the last year working for no pay at her father’s hot stone massage spa. Hae-joo, played by Lee Yo-won, is the only one of the group to have a real job, working at a brokerage firm, albeit as an assistant. Ji-young (Ok Ji-young) is a fine artist, but is unable to find paying work and lives with her grandparents in a crumbling shanty town. Twins Bi-ryu and Ohn-jo live happily together and sell homemade jewelry on the street; they seem to be doing well and mostly hang around the edges of the film, stepping up when necessary for some comic relief or to offer a dose of stability. The class separation between Yo-won and Ji-young provides the film’s central conflict, and its correlation to the disconnections in Korean life is hard to miss, both generational — the grandparents and their peers who grew up during the various mid-century wars versus the children in a time of post-martial law economic expansion — and economic — the widening class differentials that occur when a country modernizes under capitalism, enriching some, but definitely not all, of a populace.

But more than that, Take Care of My Cat is about these specific women and the strategies they employ to cope with the changing world around them. Yo-won, increasingly hollowed out and made shallow by the trappings of her success, becomes more and more cruelly indifferent to Ji-young’s suffering, while Ji-young retreats further and further into herself, eventually shutting down entirely (and finding herself in jail because of it). Tae-hee, for the most part, navigates between them both. She isn’t as greedy as Yo-won, but she’s dissatisfied with her family’s expectations that she work for free (and the fact that they seem to expect her, as a woman, to serve the men — her father and brothers, who, unlike her, are given the opportunity to go to college). A bold woman with an independent streak, she considers running away to join up on a merchant ship, like a Korean Melville. Meanwhile, she spends her free time also volunteering as a typist for a poet with cerebral palsy. He doesn’t use a computer, but rather an old typewriter which, as Tae-hee notes, gives the words a satisfying clickity-clack.

Text surrounds our heroes: as early adopters of SMS technology, they’re constantly sending each other text messages, visualized by Jeong as characters superimposed on various surfaces (walls, desks, buildings) that make up their environment (it’s hard to recall a film made prior to this that displays text messages so creatively). This was also the first generation to come of age when the boundaries between the physical and digital were porous, where friendships could be built up and broken apart through words on screens as easily as in-person interactions. But the things breaking them up — class differences, family pressure, work commitments, betrayal of once-cherished values — remain depressingly familiar today. — SEAN GILMAN

A Disturbance in the Force

We all know Star Wars came out in May of 1977 and was an immediate sensation, well on its way to becoming a cultural touchstone. But even so, it was not quite yet the lumbering, multi-billion-dollar franchise we know today. Actually, the idea of something like that hadn’t really even occurred to anyone. Nevertheless, hot irons need striking, as the saying goes, and so to keep people interested and hopefully make some money in the process, it was decided that to tide people over until the release of the sequel, a television installment would be necessary. And so it was that in December of 1978, the Star Wars Holiday Special came to CBS.

Flash forward to 2023, 45 years later, and the endless ubiquity of Star Wars only partially explains why, of all things, there is a feature-length documentary about the production of that Holiday Special (only about 10 minutes shorter than the actual thing). The other reason is that the Holiday Special is remembered mostly for being a massively terrible boondoggle about which absolutely nobody has nice things to say. In fact, it was allegedly so mortifyingly bad that George Lucas himself had it pulled from circulation entirely, never to be inflicted on human or alien eyes in any galaxy ever again, in perpetuity. Well, until YouTube anyway, where you can go right on ahead and watch the dreaded thing for yourself.

And so, long story short, we’ve now got A Disturbance in the Force. Directors Jeremy Coon and Steve Kozak have assembled most of the surviving members of the production for their reminiscences, as well as a lineup of geek celebrities to share some memories or add some colorful commentary. Listen to Kevin Smith wonder aloud just why the hell anyone thought it would be cool to add Bea Arthur to the Star Wars universe — Arthur herself, in an old interview, doesn’t seem to know either. There’s Weird Al talking about how Boba Fett was actually introduced in a pretty cool animated segment (maybe the only part of the whole thing that anyone even remotely liked). But most enticing are the various writers and producers sharing conflicting accounts, not only of who worked on what parts, but of who deserves the most blame.

A Disturbance in the Force shares one notable thing in common with its subject: both are largely unnecessary, but also fairly amusing. There aren’t any surprises in store structurally or stylistically, and for hardcore fans, this likely maxes out as a remedial but amiable time-killer. Anyone who’s never heard of the Holiday Special will probably get a little bit more of a kick out of it, and the documentary does boast plenty of clips of the woebegone special itself. Ultimately, the best compliment one can pay A Disturbance in the Force is that what’s included is so tantalizingly stupid that plenty of viewers are likely to go seek out its inspiration as soon as the credits roll. — MATT LYNCH

Good Condition

As a working actor for the last two decades, Frank Mosley has quietly amassed a remarkably varied body of work, from bit parts in films by the likes of David Lowery and Shane Carruth, to larger roles in smaller films like Freeland and Shoot the Moon Right Between the Eyes. Alongside his work in front of the camera, Mosley has also created a steady flow of impressive short films (and two features) as a writer-director-editor. Outside of film festivals, there’s not much of a market for nine- to fifteen-minute narrative works, creating a kind of vacuum where genuinely exciting films like Mosley’s slip through the cracks. It’s a shame, as Spider Veins (2016), Casa de mi Madre (2016), and Parthenon (2017) are each leaps and bounds more interesting than much of the social-realist stuff that emerges from Sundance ready and primed for streaming acquisition. Mosley’s new film, Good Condition, continues his collaboration with actor/writer Hugo de Sousa; the duo also made The Event together last year, a deft bit of cringe comedy that juxtaposes de Sousa’s live-wire energy with Mosley’s cool and collected straight man persona. Good Condition pushes that dynamic to a whole new extreme, with de Sousa seeming perched at the precipice of a complete emotional breakdown for the entirety of the film’s nine-minute runtime.

The film begins with de Sousa approaching a house. The street is deserted and no one answers the door, so de Sousa begins texting whomever he is supposed to be meeting. He’s here to pick something up, which in short order is revealed to be a small IKEA-style side table. It’s clean and looks new, but is otherwise totally unremarkable. Yet de Sousa evinces an almost orgasmic level of excitement at this banal object. He gently touches it, caresses it in fact, even placing his cheek against the flat table top as if about to embrace it — the encounter resembles nothing less than the apes staring in awe at the otherworldly monolith in 2001. But things suddenly go awry, and the film’s dark humor comes mostly from de Sousa’s outsized response to a minor setback. It’s a simple setup, but one that Mosley manages to imbue with a kind of creeping dread. It’s downright ominous in execution, and it’s no small feat to conjure such a palpable mood within these strict parameters.

One of Mosley’s primary gifts as a storyteller is the ability to suggest lives for his characters outside the framework of the film itself, the idea that these people existed before the movie began and will continue on even after the camera has been turned off. Mosley is particularly adept at sketching in character traits and suggesting volatile interpersonal relationships, from the sexual gamesmanship that threatens to turn violent in Parthenon to a lifetime of pain and regret in Casa de mi Madre. As funny as Mosley can be in the right acting role, it’s clear that his directorial choices lean toward the darker end of the spectrum. Spider Veins features a particularly brutal argument between two women, only for the camera to reveal via reverse shot that they are performing for an audience. Even The Event, the most outwardly amusing of Mosley’s shorts, suggests an unhealthy (if loving) relationship between two roommates, both struggling filmmakers. There’s an entire world of fascinating oddballs contained in these short films, and Good Condition continues that trend; anyone interested in contemporary American cinema needs to be keeping an eye on Mosley. — DANIEL GORMAN

Select Films from Fantasia Retro

The programmers at the Fantasia International Film Festival can be counted on, year after year, to assemble a strong lineup of retrospective screenings, from new restorations to rarely seen 35mm prints. The 2023 edition was no different, with its 4K restoration of Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy and Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy among some of its highlights. But there were other notable titles this writer had the opportunity to view, and below is a roundup of those that left a considerable impression.

Patrick Tam’s My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, from 1989, left the biggest impact. It’s a film somewhat at war with itself, as one feels Tam being pulled on one hand toward pulpier or more mainstream elements of the Hong Kong film industry, and to his more eccentric personal style on the other. Far from feeling like a compromised production, though, the film manages to blend these competing affects and aesthetics seamlessly into something entirely its own, clearly indebted to the tropes of heroic bloodshed films and the most romantic of melodramas, but transcending into what Sean Gilman has called “Romantic Bloodshed.” In Tam’s version of this world, to yearn is to exist and vice versa; the only thing promised is tragedy. Its characters, like us, are nevertheless drawn intoxicatingly further and further inward, unable to turn away from fate.

A similar intoxication beguiles while watching A Chinese Ghost Story, the legendary Hong Kong fantasy-swordplay film from director Ching Siu-Tung. Even though the English subtitles on the screening’s 35mm print seemed like a particularly poor translation, not a bit of the film’s saturating stylization is missed. Often compared to The Evil Dead, A Chinese Ghost Story is a true horror-comedy, swinging from gross-out effects work to absurd drawn-out gags, and back to blissful wire-fu action sequences with ethereal villains and graceful heroes. By the time we jump to Wu Ma, an all-time Hong Kong cinema veteran who is perhaps best-known for this role, rapping an incredible Taoist ditty through the forest while gusts of leaf-filled wind swirl maniacally around him, it’s clear we’re in the midst of an entirely unforgettable cinema experience. The film moves rapidly, barely resting for even a moment on images, both grand and eternally beautiful, as well as those of zombie-skeletons moving in stop-motion work that somehow even seems lovely. And as a bonus: the film is yet another reminder that the best foley sound is found in the billowing robes of a wuxia warrior.

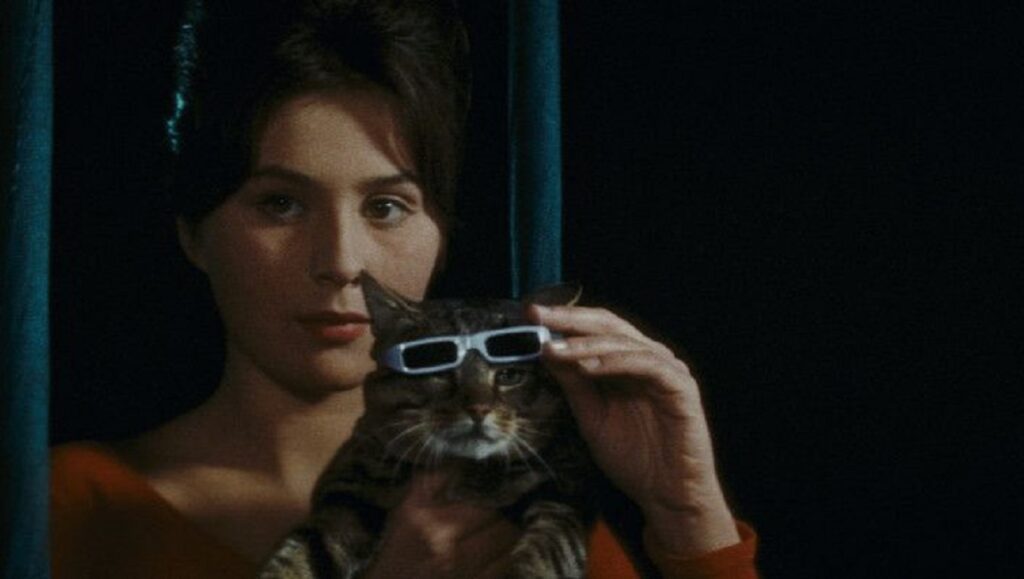

But this writer was already a keen, fluent fan of these two filmmakers, and of Hong Kong cinema more generally. The real surprise of the retro program, then, came in The Cassandra Cat, also known as When the Cat Comes, a 1963 Czech New Wave film directed by Vojtěch Jasný. If you’re familiar with The Cremator or Closely Watched Trains, you might be able to anticipate some elements of Jasný’s film that are typical of the New Wave, including an absurdist approach to comedy and a satirical take on politics (including the region’s particular postwar communism). The Cassandra Cat, though, is not quite as cynical as those films tend to be, opting instead for a brighter, looser level of cutesy pandemonium. Presented in a 4K restoration by the Czech National Archive jointly with Janus Films, what stands out most are the film’s colorful flourishes, where characters are revealed to be their “true colors” once the titular cat lays its eyes on them, chaotically dancing around awash in red, yellow, purple, or gray through exhaustive scenes of manic frenzy. In some ways, The Cassandra Cat resembles Věra Chytilová’s Daisies from a few years later, especially in the impression it lends of being caught within an unstoppable whirlwind that seems to belie meaning, except when laid out together like a structure of feeling. The political undertones to the sustained anarchy are a bit less obvious in this case, as Jasný seems to rib more lightly on the corruption of the elite, but part of the gambit is, of course, the straightforward nature of what we’re seeing, the very literal visualization of revealing the inner self through garish splendor. We are, quite warmly, invited to enter this environment with the help of Jan Werich as our host, peering in on the lives of the townspeople and establishing for us the lay of the land both visually and thematically. It would be too easy to call what we see psychedelic, or even pop art, for this is a far more specific fairy tale, in which children learn about the sinful nature of their parents and of the adult world through a madcap fantasia of whimsical havoc.

Staying within the realm of Czechoslovakian fairy tales, Juraj Herz’s take on Beauty and the Beast likewise returns us to the land of cinematic yearning and breathtaking creature design. Presented in a new 2K restoration by Národní filmový archiv, courtesy of Severin Films, this Beast is a wondrous birdlike figure, draped and moving like the Phantom of the Opera around his dank and dark castle. Herz, by this point already an international success as a New Waver, emphasizes the troubling and truly terrifying elements of this classic story, reveling in shadows of the moon and a bizarrely grounded underworld of lurking creatures and decaying corridors, through a moral about wealth and the self, rendered in Gothic detail. All this is counteracted by the Beauty, named Julie and played with endlessly buoyant awe by Zdena Studenková, a character so willful, optimistic, and persistent that you can’t help but find yourself fully in her corner, fervently rooting for her as she navigates a horrific curse she volunteered for while nevertheless falling under its spell. This give and take, the dreary and the spirited, defines this grim and decadent interpretation and the tragic romance at its center, a conflict of psychological and cultural values made lushly and eerily manifest.

All singular works, meritorious in unique ways and reflective of distinct movements in cinema history, these four highlights from Hong Kong and Czechoslovakia, taken together, once again affirm Fantasia’s careful, unbeatable genre programming. — JAKE PITRE

Comments are closed.