It’s impossible to talk about 2023 without talking about Barbie and Oppenheimer, two very different films that became seismic pop culture sensations, crushing the box office while garnering no small amount of critical acclaim in the process. This is, of course, the Hollywood dream: four-quadrant pictures that appeal to huge swaths of the population, both packing movie theaters and generating awards chatter. Much like last year’s Top Gun: Maverick, these are the movies that are supposed to show how well the system works; i.e., people still love movies and will still venture out to theaters if you give them something worth going for. These are the kinds of movies that are going to save the cinema. Similarly obvious is that this approach articulates an extremely rosy view of the year in review. For every success story like the Barbenheimer phenom, there were even more failures; mighty juggernaut Disney floundered, releasing one overpriced bomb after another; the Marvel machine, a money-printing factory for the better part of a decade, has sputtered; and on that note, the entire superhero genre is showing clear signs of decline (witness the husk of the misbegotten DCEU limping through empty multiplexes). What will replace the superhero movie at your local theater? It’s hard to say, although based on this year’s winners, you can bet there will be more prestige biopics and a Mattel shared universe. The fact of the matter is, it’s a fool’s errand to predict what audiences will and will not respond to; as Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote years ago in his essential book Movie Wars, “Then and now, the operations of the media-industrial complex have been predicated on certain highly questionable assumptions about the audience, and charting box-office grosses to ‘prove’ those assumptions is merely indulging in a self-serving form of circular reasoning.”

The truth of the matter is, when pundits and awards prognosticators declare a year of film “good” or “bad,” they’re almost always talking about what played at large, mainstream movie theaters to some reasonable degree of success. Corporations, through mergers, acquisitions, tax write-offs, and the never-ending quest for shareholder value, continue to narrow avenues for genuine artistic expression in commercial cinema. We here at InRO aren’t staking out any anti-mainstream entertainment stance (you’ll find a couple of blockbusters and even a superhero movie on our consensus list), but we do hope that we can encourage readers to dig deeper, look further, and otherwise expand their horizons when it comes to what constitutes “the year in film.” Jean-Luc Godard once stated, “I like to consider myself an airplane, not an airport.” Film criticism can’t tell you, the reader, how to think or what to feel, but it can help you make a journey. The below list reflects InRO’s 2023 journey. (**The first part of our Top 25 feature, covering films #11-25, can be found here.)

10. Trenque Lauquen

Before any of the many fascinating characters populating Trenque Lauquen, or even its title (directly taken from the name of the Argentine city where the drama takes place), appears on screen, we hear a firm, confident, manly voice utter the film’s first word: “Exactly.” The image takes time to process this, seemingly unsure of what it must produce to complement the spoken word. Meanwhile, the same voice, still confident and declarative, continues to speak, demanding clear answers about something neither we nor (we presume) it knows much about. Once the image eventually catches up to the sound, there’s some clarity. This annoyingly cocksure man, hellbent on establishing that our protagonist’s disappearance is “not a mystery,” is, in fact, her boyfriend: a central figure during the first half of the film’s 260-minute runtime who mysteriously just goes missing after that. It’s as if the film — almost vindictively — punishes him for his strong-willed certainty. The vindictiveness only extends to him in director Laura Citarella’s sprawling, genre-shifting, perspective-flipping film; the mysteriousness, however, envelopes everything and everyone in Trenque Lauquen.

Citarella is, in many ways, following in the footsteps of fellow Argentinian filmmaker Mariano Llinás’ genre-hybrid works (La Flor, Extraordinary Stories), which she produced. Trenque Lauquen, like Llinás’ oeuvre, is thrillingly unclassifiable. For one, its status as a “film” itself is shaky, bolstered mostly by its success and recognition at the Venice and New York Film Festivals. Unlike other auteurist projects with ballooning runtimes that prepackage themselves as Cinema, Citarella’s film offers plenty of opportunities to dip in and out of its world. Its evenly split two-part format, each half sub-divided into multiple chapters (eight in part one, four in part two), almost qualifies it as a miniseries; its penchant for digression, especially the decision to focus as much on characters looking as opposed to doing, also makes it, at times, feel something like a visualized novel. Alternatively, the film’s multiple mysteries, at times rhyming, at other times not, give the impression of watching a simulation of an open-world video game where characters choose side missions at their will, unperturbed by the impact it may or may not have on the central narrative.

This fluidity extends beyond the film’s medium specificity to its genre, style, and plot. Ostensibly, the film is a modern-day riff on Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960). Here, the sudden disappearance of a botanist, Laura (Laura Paredes), leads to a search that reveals more about the two men looking for her than the missing person herself. But whereas Antonioni’s film deliberately avoided exploring the vanished person’s perspective, Citarella’s film, especially in Part Two, revels in exploring it without ever explaining it. In doing so, the film becomes a prismatic reflection of a woman: different people look at her through different generic lenses — first coldly investigative, then giddily romantic, and then a mix of both — only for us to find that the generic space she’s trying to occupy may be science-fiction horror. Or internalized queer romance. Or contemplative slow cinema. Or a bit of all of them. She is the mystery here, whom neither Citarella nor the translucent Paredes ever wants to solve. And neither should we. — DHRUV GOYAL

9. Knock at the Cabin

It’s admirable that M. Night Shyamalan has stuck to his guns the way he has, considering his intelligence is routinely underrated or called into question outright by critics and audiences more eager to get their licks in than engage with his work in good faith. But there’s no two ways about it: Knock at the Cabin is Shyamalan’s greatest, most moving work to date, a beautiful parable reflecting on faith, love, and sacrifice. It’s also a film whose theological convictions are bound to be misunderstood — if they are seriously considered at all — as most mainstream cinema retreats further into self-awareness and can only muster limp sentimental scientism (repackaged as “positive nihilism”) in response to our societal and spiritual crisis. The high-concept premise of four strangers holding two fathers and their adopted daughter hostage, claiming one member of their family will have to willingly sacrifice themselves in order to save the rest of humanity, provides an ideal jumping-off point for the director to indulge in yet another intensely claustrophobic genre exercise. Shyamalan, having fully let his style off the leash with 2021’s Old, softens some of his more eccentric impulses to suit the emotional tenor of the script, but nonetheless dazzles with unorthodox compositions, bold camera movements, and startling close-ups of tormented faces.

The fact that the family being held hostage is headed by “a single-sex couple,” as Dave Bautista’s Leonard so carefully puts it, adds another layer to the tense dynamic between the family and the intruding quartet. One of the fathers, Andrew (Ben Aldridge), is convinced they are being targeted by bigots, a conclusion shaped by a lifetime of endured homophobia and a particularly traumatizing instance of violence. Eric (Jonathan Groff), by contrast, spends the first hour in a concussion-induced fog from which he only slowly emerges, making for a more sedate presence next to the desperate and angry Andrew. Seeds of doubt are sprinkled throughout, but these pose more of a challenge for the captives than they do for the audience. Shyamalan has never been one for subtlety, and so the question of how true the intruders’ claims are soon gives way to the question of whether or not the family will be able to make the sacrifice that’s been asked of them. But is humankind even worth saving? Andrew isn’t so sure: “How about I show you photos of kids who have been tortured and killed, lying in piles?” he asks Leonard. “You want to make a case for humanity to go on, you’re gonna lose.”

And yet, even when acknowledging humanity’s darkness, Knock at the Cabin remains uninhibited in its belief in the future. Faced with the end of the world, Shyamalan doesn’t stoop to misanthropy, nor does he offer platitudes or cheap cynicism. His vision of faith is unquestionably a frightening one — why would a loving God force anyone to make a choice as impossibly cruel as that? — one that melds Lovecraftian horror with Jobian anguish. Job looked beyond himself while in the throes of immense suffering — “For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth.” (Job 19:25) — and with his latest, Shyamalan invites us to do the same. The skies will eventually clear and the sun shine brightly again — all we need is a little faith. — FRED BARRETT

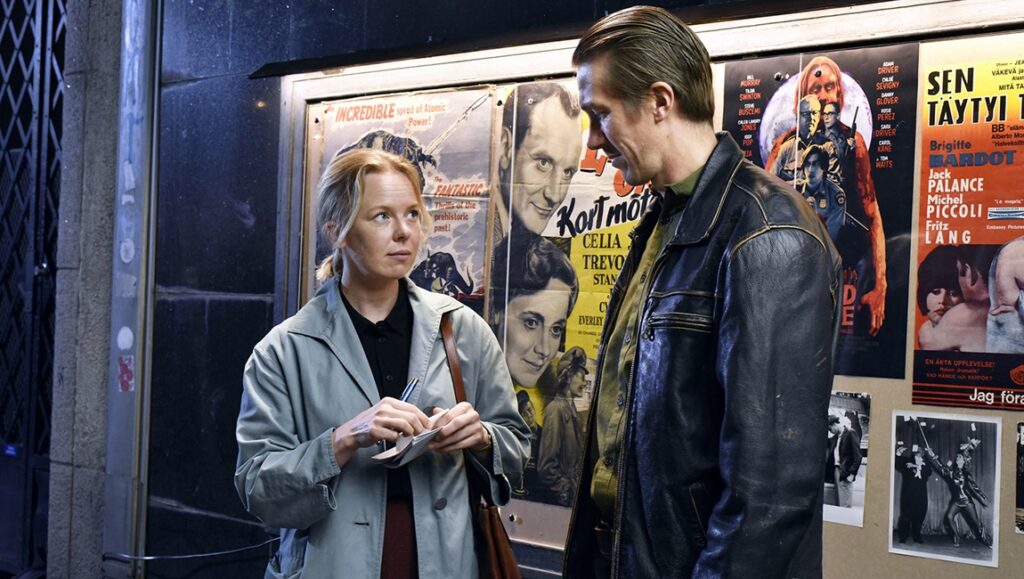

8. Fallen Leaves

It’s right to view Aki Kaurismäki’s singular aesthetic as something anachronistic. Despite rapid changes in the world, the Finnish veteran director is one of few still dedicated to the gradual and patient artistic evolution of his work, allowing him to revisit and refine his narrative and formal strategies film by film — a quality also visible in the oeuvre of the master filmmakers Kaurismäki is continuously inspired by: Robert Bresson, Yasujirō Ozu, and Charlie Chaplin. It seems, then, that the endeavor to reach perfection through persistence is his ultimate priority. Fallen Leaves, playfully dubbed as the “lost fourth part” of Kaurismäki’s Proletariat Trilogy (comprising Shadows in Paradise, Ariel, and The Match Factory Girl), follows a supermarket’s grocery stocker, Ansa (Alma Pöysti), and a construction worker, Holappa (Jussi Vatanen), two lonely and entangled souls who, like many of the director’s marginalized blue-collar outcasts, face everyday struggles in modern-day Helsinki.

In Fallen Leaves, the city appears to be under continuous reconstruction and renovation, its citizens in search of some kind of meaning, whether that’s found in peaceful liberation, financial stability, or long-lasting romance (ideally, all three). Here, there’s an obvious contrast between Kaurismäki’s protagonists, the post-industrialized social backdrop, and the post-consumerist environmental cityscapes they’re set against. Unlike the damp autumnal backgrounds and often dingy building walls, their presences are usually depicted through vibrant colors, as if these defenseless and fragile bodies are essentially animated by the most profound human affection and dignity. They try to resist, ignore, or defy the surrounding circumstances — in an early scene, Holappa lights up a cigarette right in front of a “no smoking” sign. Such a sense of empathy, regardless of the quotidian hardships endured, is the film’s driving force.

Kaurismäki’s masterful timings — of the performers’ actions or inactions, sudden or prolonged pauses, and dialogues — are crucial both in the development of his modest, sympathetic story and in order to extract a kind of Kafkaesque or Beckettian absurdism. They also prove instrumental in motivating vitality from beneath the dead façade of this somewhat purgatorial world, where its inhabitants mostly find themselves idle in dive bars, drinking, smoking, listening to music, or indulging a little karaoke — in other words, they don’t really spend time as much as they try to kill it. Whether via an old radio (broadcasting the news of war), an antique jukebox, or a local arthouse movie theater — where Kaurismäki pays tribute to Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die and also draws similarities between his characters and their zombie-esque existential conditions — the closed-off, isolated spaces of Fallen Leaves connect themselves to the larger outside world, with even the names of the bars (California or Buenos Aires) intentionally evoking the recurring motif in his other off-kilter and subversive romantic dramedies, where their characters dream of farflung, romanticized destinations.

The sonic ambiance of Fallen Leaves, meanwhile, continuously governed by silence and pauses, emphasizes the drama of even the slightest sounds (beeps, buzzes, clicks), while its meticulous staging and attention to postural gestures, pensive facial expressions, and physical distance (or proximity) between characters work to develop the film’s deadpan comedy. And these aesthetic textures lead to the film’s most distinctive, enduring quality: the way Kaurismäki manifests this world of mundane, repetitious living within an enveloping atmosphere of drunkenness, dreaminess, and drowsiness, developed through various scenes of imbibing, falling asleep, waking up, and, later, an accident-induced coma. Following this logic, as much as Kaurismäki’s personal cinephilia (especially, his love for silent comedies and Chaplin, to whom his final scene pays homage) is evident in almost every moment throughout the film, it’s also possible to interpret Fallen Leaves as the manifestation of an imaginary state — of unfulfilled desire — for Ansa and Holappa. Whether one prefers, then, to subscribe to the ostensible happy ending Fallen Leaves’ offers its lovers or the more pessimistic conclusion that easily can be drawn, what’s certain is that the film’s beauty, grace, and sweet poignancy leave an undeniable impression. — AYEEN FOROOTAN

7. Showing Up

Kelly Reichardt’s movies have always been concerned with the little moments that most of our lives are made up of — understanding the everyday dramas as more consequential than the cataclysmic and supposedly defining events — and seldom have those moments been smaller than in Showing Up. Michelle Williams, in her fourth collaboration with Reichardt, plays Lizzy, a stiff-shouldered and poorly dressed artist trying to complete her small exhibition of sculptures while constantly being interrupted by a quiet farce of annoyances and distractions. Some are bigger than others, from her landlord and fellow artist jovially procrastinating on fixing her hot water supply to the burden of making small talk with colleagues at her teaching job, but she refuses to endure any of these indignities with grace.

It’s a narrative thread that perhaps brings us closer than ever to Reichardt herself, who also has to take a teaching job to pay the bills, despite being one of America’s greatest working directors. At least, the connection to Showing Up feels similar if one references her reviews on RateMyProfessor.com, which describe a “terrible sense of humor” and curtness similar to those found in Lizzy. Without blindly accepting the validity of such critiques, it’s not hard to imagine how frustration like this would be born; the fact that Reichardt has to work a day job paints a pretty depressing portrait of the industry around her. If Showing Up, like First Cow before it, being released by the hip A24 seemed like a blessing — perhaps a way to deliver her work to a wider, younger audience — that isn’t how it ultimately played out; it’s telling that’s it’s only now showing up on best-of-year lists, despite premiering in 2022 at Cannes (alongside Triangle of Sadness, for a sense of perspective). But it got even worse treatment in the U.K. (this writer’s home base), where it hasn’t been released at all. The last glimmers of hope for a theatrical run seemed to fizzle out when a Blu-Ray was announced, but suddenly a screening was listed in London, before being canceled a few hours later for rights-related reasons that it seems repertory cinemas are struggling with, too.

But among the indignities surrounding the film, and among those surrounding Lizzy’s work in-film, are little pockets of grace. Even though she pushes away all connection with her hardened façade, it finds its way to her anyway, and even though the release of Showing Up has been at once noncommittal and messy, it thankfully hasn’t stopped people from finding it. For those who have yet to, this confidently low-key and quietly resonant film waits patiently to be discovered in one mode of exhibition or another. The hope is that enough people find it while Reichardt is still working — let’s at least let her quit her day job! — ESMÉ HOLDEN

6. Killers of the Flower Moon

It would seem that the Age of the Octogenarian has descended on both Hollywood and Washington, a troubling development for the twin institutions that engineer and reflect so much of the American self-image. And while the failures of our feckless gerontocracy grow more inescapable by the day, many of their cinematic counterparts have seized the opportunity to deliver late-period work with uncommon budgetary and artistic freedom. Michael Mann, Ridley Scott, Hayao Miyazaki, William Friedkin, Paul Schrader, Frederick Wiseman, and Víctor Erice (among others) each took another bite at the apple in 2023, but it was our unofficial cinematic elder statesman who undertook the most monumental reckoning with the foundations of his art.

The main thrust of Martin Scorsese’s work has long been a poison-pen recounting of the American Dream, allegorizing the violent structures and motives of American capitalism through their reproduction outside the scope of the law by immigrant or ethnic communities. With Killers of the Flower Moon, it’s safe to say his priorities have shifted. Scorsese no longer locates the central American story as that of the strivers trying to steal what they can on the side, turning his focus instead to the inconceivable acts of theft and murder on which American society is quite literally built. Adapted from David Grann’s nonfiction bestseller, the film recounts the systematic murders of the Osage people after massive oil deposits were discovered on their land in Oklahoma in the 1920s.

Much has been made of Scorsese’s decision, apparently settled on with the input of Osage leaders, to shift the focus of the film from the then-nascent FBI’s investigation into the murders orchestrated by William “King” Hale (Robert De Niro) to the marriage between his dim-witted nephew Ernest Burkhardt (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Osage oil heiress Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone). And while there’s no shortage of classic Scorsese gangsterism in the details, the film’s frequent sidestepping of traditional dramatic payoffs for a constant sense of mounting dread and moral queasiness is among its most radical moves. Hale’s “Reign of Terror” is recreated with a staggering density of character and incident, and Scorsese looks at the crimes with the unsparing conviction of a great artist’s final testament.

In many ways, Killers forms a late-period duology with 2019’s The Irishman: despite being conceived with a scope and budget that suggests a filmmaker aware each movie may be his last, both completely drain their criminal lifestyles of any excitement or allure. In both works, the story of America in the 20th century becomes that of a completely unremarkable man who betrays the person closest to him in the world. He does this not out of any deep-seated hatred or Machivellian ambition, but out of the banal avarice and laziness that make them perfect tools for the monsters that sign their paychecks. The identification of the mechanisms of genocide in the expedient ease of following orders, of not resisting the will of power, is the most chilling and contemporary note in its meticulous study of complicity.

The film certainly isn’t above scrutiny when it comes to the questions raised by its own justly lauded epilogue, which cannily critiques its own role in the post-hoc packaging of Indigenous suffering via corporate-sponsored narratives tidily consumed by white audiences. But as a capper to a miraculous four-film run by our greatest ambassador for the potential of the art form, a recontextualizing of its past and a challenge for its future, the achievement of Killers of the Flower Moon is one to be lived with and examined as only great art can be. — BRAD HANFORD

5. in water / Walk Up

I’ve written before for Reverse Shot about the peculiar phenomenon of comparing and contrasting films written and directed by Hong Sang-soo that comes as a result of them being released in the same year. This is rendered even stranger when two films from adjoining premiere years come out during the same release year, which has happened three times thus far: the annus mirabilis of 2012 with Oki’s Movie (2010), The Day He Arrives (2011), and In Another Country (2012); last year with 2022’s The Novelist’s Film joining 2021 premieres Introduction and In Front of Your Face; and now in 2023, with the two films in present conversation.

So, while it may be purely due to the vagaries of distribution (courtesy of the heroes at Cinema Guild) that we have an outlet to consider Walk Up (2022) and in water (2023) in the same year-end breath, it provides a useful excuse to look at these two very different grand achievements, Hong’s 28th and 29th films respectively. Upon casting a very preliminary glance, and stripping these already spare works purely down to their essence, they belong to separate modes of Hong: Walk Up the sober black-and-white rumination on middle-age a la The Day After or Hotel by the River; in water the young filmmaker-centric metafiction about the artistic process of Oki’s Movie or Our Sunhi. But upon further examination, neither align strictly with either paradigm, and in fact each attach a new means of expression to Hong’s arsenal, as vivid as Hill of Freedom‘s jumbled chronology or The Day He Arrives‘ perpetual chronological quasi-resets.

In Walk Up‘s case, it is a literalization of Hong’s penchant for narrative structure, with said four-part construction corresponding to the four floors of the eponymous apartment building. Kwon Hae-hyo, in perhaps the finest role of his ongoing collaboration with Hong, gradually drifts skyward as what may be months, years, or no time at all pass him by, and the cozy spaces gradually absorb and exude the anxieties over a wasted life that implicitly hang over so many past Hong protagonists. But the constriction in location here magnifies the feeling of each space being haunted with its unique ghosts/alternate realities, and the sense that your past or future life (for better or worse) may be right in front of your face.

in water‘s gambit is both just as simple and visually entrancing as it sounds and more considered than meets than the eye. For one, the out-of-focus shots are not uniform in their look (two interior shots near the start are even in-focus); for another, the perspective they suggest — that of Hong himself, with his well-known failing eyesight — is layered onto that of a young filmmaker just starting out yet possessed with the same ruminations on mortality as Kwon is in Walk Up. And though Hong certainly isn’t lacking for great endings, what perhaps may best bind these two films as closely as any commonality is the finesse with which their final shots suddenly snap each of their associated works into startling, devastating focus. — RYAN SWEN

4. Asteroid City

Not since The Darjeeling Limited has Wes Anderson found his way this deep inside the experience of loss, and not since ever has he folded that emotion so completely into the fabric of his filmmaking. The words “played relentlessly” could have graced the title card of any of Anderson’s more recent, brimful cinema confections, except here they signify less as a show of virtuosic excess than an uncommonly vulnerable surrender to what’s always been an unsustainable pace and rhythm. Neither is “you can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep” a typical Wes witticism; and though it’s repeated, mantra-like, by a Stanislavski-esque acting instructor and a classroom full of theater thespians, its accusatory sentiment is clearly aimed at the cinema construct outside this film’s play-within-a-TV-show Russian nesting doll narrative. Anderson implicates his own consummately baroque approach here, recognizing that it has sometimes prevented his audiences from fully buying into the emotional experience of his characters.

In Asteroid City, one strategy for overcoming formal codification becomes a willfully disorderly dismantling of some arbitrary narrative barriers — a simple enough feat to accomplish since the vibrantly colorful Max Fleischer-like desert landscapes and black-and-white backstage Broadway dressing room sequences were all filmed on a single-location set anyway. But this lucid play on physical space wouldn’t mean much without the overwhelming power of the film’s central juxtaposition to motivate it: the parallel between the disappearance of something you thought would always be there and the appearance of something you never expected to see — both events serving to radically alter the scope of the universe.

It’s this seemingly unresolvable tension between two Big Ideas that tears the space-time continuum of Asteroid City, as Jason Schwartzman (brilliant here as both the recently widowed war photographer Augie Steenbeck and the queer method actor who plays him on stage) begins questioning his characters’ own quixotic behaviors, and even the number of planets in our solar system is gently called into question. Anderson mobilizes timeless sci-fi tropes alongside our own present’s unlikely science reality (quarantines and lockdowns) to activate his most searching, discursive study of human resilience. One potential takeaway offers at least some path to perseverance (“Just keep telling the story”), while another registers as far less optimistic (“Got no future, got no hope / Nothing but the rope”). — SAM C. MAC

3. De Humani Corporis Fabrica

The strongest words of praise that one can offer De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 2023’s best documentary, is that the film more than delivers on the promise made on its poster: “The human body as you’ve never seen it before.” Where this year’s other celebrated documentaries, from filmmakers like Frederick Wiseman, Wang Bing, and Claire Simon, represented exercises in repetition and patience, co-directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s exploration of physical extremity is a true test of endurance. Throughout the movie, no dermatological surface is too firm to resist medical instruments nor too delicate, and disturbing physical malformations are indexed and cataloged rather than fully contained. If this depiction of healthcare in practice is often as hard to watch as it is visually arresting, desensitization is at least part of the goal here. By foregrounding both surgical technique and sensorily overwhelming stimuli, De Humani Corporis Fabrica imagines a medical professional class — and by extension, a modern society — whose mastery over the human body has arguably outpaced our empathetic capabilities.

Probing the furthest reaches of humanity is, ironically, familiar terrain for Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, whose 2012 documentary Leviathan blurred sensory details of life working on a deep sea fishing boat into an abstracted hellscape, and whose next film (2017’s Caniba) unpacked the psychology of one of history’s few recorded cannibals. Abstraction is central to the aesthetics of De Humani Corporis Fabrica as well, though just as often do the experimental filmmaking duo bear fruit from contextualizing shocking imagery within its anatomical function. An earlier scene of drilling into a man’s skull, for example, flows into the camera view of pathways in his gray matter, only to reveal later what we are actually watching, while a later optometry procedure — replete with fluid injections and directed flashes of flight — transforms the eye in question from seeing object into cinematic canvas. Compared to 2023’s higher-concept, world-and-time-traveling cinematic journeys, and even the earlier collaborations of Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, De Humani Corporis Fabrica is a testament to the enduring returns of a microscopic and recognizably organic approach to storytelling.

Were stunning footage of the human body all that De Humani Corporis Fabrica had to offer, it would still be among the year’s foremost achievements in filmmaking, yet this imagery — shot over several years in multiple hospitals — is affixed to a social stratum that confounds our perception of the film’s onscreen medical mastery. Casual small talk and petty office gossip during operations establish a beset-upon hospital workforce who are less stunned than they are inconvenienced by their patients’ maladies. Scenes featuring dementia patients further expose the gulf between technological efficacy and the ability to provide authentic social care, and the unglamorous atmosphere of the doctors-only rave that concludes the movie is ultimately less a celebration than a ceremonial release of tension. Few, certainly, would argue that working in a hospital is easy, or that interpersonal decency writ large peaked in 2023, though rarely are our present advances and limitations rendered with this degree of simultaneity. In De Humani Corporis Fabrica, bodies, souls, and the superstructures around them are all exposed. — MICHAEL DOUB

2. May December

In his heyday, Douglas Sirk’s movies split viewers into two factions. Many critics and intellectual-types dismissed his work as populist claptrap: emotionally manipulative and saccharine to the point of accidental farce. Yet his films triumphed with general audiences. Most moviegoing masses accepted his heightened dramatic scenarios and attuned themselves to their pathos, anguishes, and longings. Sirk’s own perception of his work synthesizes both perspectives; during his 1970s critical resurgence — spearheaded by a new generation of film scholars — he confessed to certain ironic detachments. For him, Lana Turner’s heroine from Imitation of Life was a half-punchline: a ludicrously-adorned, class-ascending moviestar towering self-centered against a backdrop of real tragedy. By Sirk’s own admission, his vision of melodrama was rooted in a complex mélange of irony and sincerity.

It only takes a quick glance to recognize how Sirk’s spirit looms over Todd Haynes’ films. The latter’s early shorts (e.g., Superstar and Dottie Gets Spanked) and first feature (Poison) churn middle class tragedy into camp-melodrama. Yet over time, as he transitioned into a pantheon of Hollywood prestige, Haynes’ ironic bite subsided; there’s little camp, for instance, in the swooning romance of Carol or the proceduralism of Dark Waters. And so, May December arrived unexpectedly. The film is apex Haynes, welding heartfelt melancholy and pitch-black comedy, and the narrative follows a Georgian married couple: a middle-aged, cake-baking diva (Julianne Moore) and her two-decades younger husband (Charles Melton), whom she groomed and statutory-raped at the age of thirteen. Their “affair” was a tabloid sensation of the ‘90s à la Mary Kay Letourneau, although they now inhabit a wholesome façade of white-picket suburbia. Yet with their teenage children graduating and a nosey method actress (Natalie Portman) prepping for an adaptation of their story, the couples’ idealistic veneer ruptures as deep-repressed feelings surface.

May December announces itself with a stinging, detached piano melody (plucked from Michel Legrand). It’s an ominous overture: the recognition of a violent undercurrent the movie’s images conceal. A few moments later, Moore’s pedophile-matriarch putters through her sunny kitchen, gasping with horror at the revelation that they’re undersupplied for hot dogs. Simmering dread turns ludicrous. Moore’s performance is gargantuan, like Bette Davis reincarnated. She embodies an all-American predator, an emotional terrorist, and a testament to the sinister powers of compartmentalization: all disguised with a goofy lisp. Though Moore is terrifying, her larger-than-life histrionics are so transparently narcissistic that it results in an all-timer of darkly comedic performance. Opposite her is Melton as her husband, a man slowly realizing what’s apparent to everyone around him: his whole life’s been stolen. He was foisted into fatherhood as a teenager and now lives his mid-30s with the inexperienced naïveté of an adolescent, and over May December’s duration, we watch a man flirt with introspection for the first time in his life. As funny and perverse as the movie often is, Melton’s melancholy is its core. In this way, Haynes pulls the rug from his characters’ meticulously ordered world, uncovering cycles of exploitation woven into the fabric of American celebrity and domesticity alike. His best film yet, May December grasps the fundamental tension of Sirkian melodrama: that in the American saga, pathos and absurdity are innately linked. — RYAN AKLER-BISHOP

1. Pacifiction

In an interview with InRO contributor Alonso Aguilar, the Catalan filmmaker Albert Serra consecrated his filmmaking ethos in “sovereign images”: images which “go beyond social or political leanings,” sometimes “unjustly” so, and which necessitate the viewer making an “active effort to endure” them. At first glance, Serra’s remarks appear insular and disdainful — an aesthete’s retreat into the inner bounds of subjectivity. But much like the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, in whose prose the virtues of tedium found their scintillating expression, Serra’s oeuvre repurposes its enervating aestheticism to electrifying ends; his latest, Pacifiction, charts contemporary malaise neither through pulpy realism nor inscrutable fiction. Fictions, to be sure, form the bedrock of sun-drenched Tahiti, atop whose waves and winds we calmly observe the unfolding of uncertain proceedings. But the register they adopt is keenly nebulous, lacking the sweet naïveté of fantasy and lingering even less on embodied meaning. The film’s heart — not exactly of darkness, as was the predominant post-colonial metaphor — is one of sensual dislocation: low-lying anxiety mixed in cocktails of suave symbolism, brimming furor mellowed by the lights of exotic neon.

The stakes of Pacifiction are reduced to specters beyond the horizon. Nuclear testing, a program established by French Polynesia’s colonial masters but withheld after opposition from both foreign governments and indigenous activism, is rumored to be back, dressed in whispers and then in the crew of taciturn seamen led by their unnamed admiral (Marc Susini). Morton’s, a nightclub seemingly removed from its elemental surroundings, becomes their haunt. For the High Commissioner, the mysterious De Roller (Benoît Magimel) whose first name eludes us, their motives and movements appear increasingly slippery, as do those of the local actors with whom he consorts, coerces, and compromises. Just as the kingmaker’s privilege is steadily denied him, however, so is his phantasmic presence made more transparent. “I’ll watch from a distance,” he informs the performers mounting a cockfighting dance, with an air of affability dispensed by default to virtually all his interlocutors. Positioned both as the benevolent face of a difficult legacy and a figure behind the scenes pulling off a cosmic balancing act, our hero is, in effect, neither. His impotence, staggeringly at odds with the violence which marks the dance, only blooms as the island’s lush, languid rhythms infiltrate the film’s sound and landscapes. The negative of its postcard pictures is beautiful and terrible torpor.

For Pessoa, these affects marked the vividness of dreams. Dreamer though he was, the writer rarely sought a distinction between sweet and nightmarish ones, and the resultant panoply of sirens and colors reflected and rejected the banality of real existence in equal measure. A similar contradiction is entailed in Pacifiction, its gargantuan ambitions consciously subverted by a dearth of meaningful action. Coasting along the Pacific on jet skis, its characters lose themselves to the waves, death knells underneath whose groans lurk the submarine De Roller spots once through his binoculars and then never again. The film’s portmanteau title curiously submits itself to another reading aside from its novelistic one; insert an “a,” and the azure blues of the imagination manifest in reality as attempts, both geopolitical and individual, at pacifism. Running diplomatic errands in white — his suit, Mercedes, charter plane — and eager to please all, De Roller, symptomatic of modern middle management, eventually finds all the world a stained glass, enslaved to machinations before and after himself. If appeasement does not work, and aggression lies beyond one’s ambit, the last and only resort is apathy. Subtitled in French as “torment on the islands,” Pacifiction reclaims its one last sovereignty as witness to this apathy, all its beauty and bloodshed, before the world falls apart. — MORRIS YANG