Stan Brakhage’s 1958 film Anticipation of the Night could perhaps be likened to the late-19th and early-20th century tonal compositions of Arnold Schoenberg. In works such as Verklärte Nacht (1899) and Pelleas und Melisande (1903), the composer had not yet broken with the tradition of Western tonality, and so compared with later compositions like Five Pieces for Orchestra (1909) or Pierrot Lunaire (1912), these early works may sound comparatively tame. And indeed, the early work of Schoenberg entered the repertoire more readily than his more experimental pieces, a situation that has persisted for more than a century. Still, it’s important to recognize that in those early tonal works, Schoenberg was pushing dissonance and Wagnerian chromaticism to the breaking point. Despite their tonal center, those early efforts were highly controversial at the time of their premieres, rejected by many as incomprehensible. Hearing the works now, it’s fairly evident where Schoenberg would go next.

It may be reductive to compare Schoenberg’s break with tonality with Brakhage’s development of a radically new cinematic language, one that largely abandoned such fundamentals as narrative, character, and coherent spatial orientation. But there is a connection between the two artists in the sense that, following the precepts of high modernism, these men were exploring potentials they both believed were inherent in their chosen medium. For Brakhage, this meant treating the camera as an extension of the filmmaker’s eye and body, organizing his films according to private, even idiosyncratic leaps in memory, gesture, and impressionistic light. And of course, the artistic paradigms “overturned” by both Schoenberg and Brakhage have continued unabated, since the consequences of their invention could not be accommodated to dominant aesthetic preferences.

Experimental film scholar P. Adams Sitney, in his seminal book Visionary Film, identifies Anticipation of the Night as the film with which Brakhage made his first breaks with the tradition that spawned him: the Surrealist and poetic films of Cocteau, Buñuel, and above all Deren. Those works operated within a Freudian framework of dream logic and internal psychology, and while they abjured the everyday, observable world, their radical breaks in film language were centered on performers who were pictured onscreen. The dramatic suspension of gravity and unified offscreen space one sees in Meshes of the Afternoon (1943, co-directed by Alexander Hammid) is inseparable from the cyclical paces the “Maya” character undergoes. It was in attempting to break with this onscreen figure, the identificatory human presence in the film, that Brakhage created Anticipation of the Night.

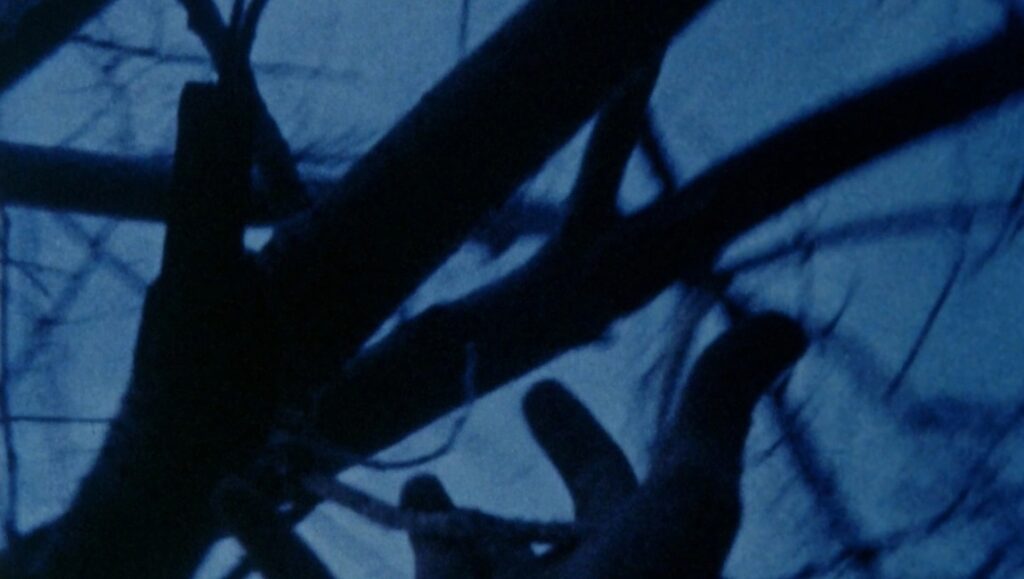

As Sitney writes, “Brakhage takes up the opening of Meshes of the Afternoon […] We see those parts of the body which a subject sees of himself: the shoulders, the legs, and especially the outlined image he projects in a shadow.” In other words, Brakhage produces a kind of first-person narrative of private experience, but one that does not duplicate the experiencing subject onscreen as a performer. Where conventional cinema offers the spectator as illusion of physical and psychological totality by depicting an entire actor (or actant) onscreen, Anticipation of the Night offers something altogether more fragmentary, a vision akin to what the infant sees of themselves prior to the Lacanian mirror stage: disconnected limbs, discontinuous movements, and above all an externalized, alienated impression of wholeness, the shadow on the wall as a fictive “self.”

Sitney describes Anticipation as a “lyric film,” one connected to the first-person consciousness of poetry. “The lyrical film postulates the film-maker behind the camera as the first-person protagonist of the film. The images of the film are what he sees, filmed in such a way that we never forget his presence and we know how he is reacting to his vision.” In his later work, Brakhage conveyed that sense of presence primarily through camera movement and editing, rather than providing an onscreen avatar for his role as “the filmmaker.”

There were, of course, exceptions, when Brakhage would turn the camera on himself. He appears in Window Water Baby Moving (1959), Dog Star Man (1961-64), and other works. But with Anticipation of the Night, Brakhage seems to be actively struggling with the problem of self-representation. How can he communicate his presence to the viewer without appearing as a performer? After the scratched-in title, the first image we see is a conic shaft of light on a dark floor, created by light coming through a window. We then see Brakhage’s shadow cross in front of this light. Next, we see a group of colored lights spiraling randomly in a darkened field of vision. This is handheld photography of exterior lights, with Brakhage shaking the camera. We then see the window light again, from a reverse angle, and the wild outdoor lights again.

The first few minutes of Anticipation alternate between interior and exterior light, although this itself is paradoxical. After all, it is outside light that is pouring in through the window, and so despite the immediate shock of Brakhage’s cinematic grammar, we can understand that Anticipation aims to problematize the distinction between interior and exterior, the mind and the world. Within these first few minutes, Brakhage gives us close-ups of a glass sphere containing water, a red flower, and some leaves. Brakhage repeatedly picks up the object, moves it around, and seems to use it to create unstable, striated shadows on the wall.

Now, considering Brakhage’s oft-stated respect for Orson Welles, it’s entirely possible that this handheld object is an echo of the paperweight that Kane drops at the moment of his death, the talisman that provokes his memory of maternal love and wholeness, now shattered. But above all, this glass sphere is a kind of alternate lens, something Brakhage can use to physically manipulate light. These two meanings are by no means mutually exclusive, since Citizen Kane (1941) is a film precisely about the struggle between a public man of the world and his interior perceptions. And as a very early attempt by Brakhage at articulating a phenomenological cinema, something tactile yet absolutely based in his own subjectivity, Anticipation of the Night may, consciously or not, strive to make itself understood by forging connections with film history.

The first 10 minutes or so of Anticipation reflect Brakhage’s taking his camera out into the world and charting the various ways it can move in space, recording intensities of light. There are landscape shots taken from a moving vehicle, whip-pans across the sky and tree line, and an almost clinical inspection of decorative lights in a neighborhood at dusk. Then, returning to the house, we see the window opening outward, and Brakhage’s shadow moving across the wall. The filmmaker is not simply going outside, but depicting himself going outside, leaving the safety of his home but, again, not exactly striving to accommodate himself to the demands of the everyday visual world. Rather, he is taking his interior vision outside, attempting to reshape it in accordance with his private ocular experience.

Shortly thereafter, we see the image of whirling grass, arcing stripes of green, blue, and white. And then we see a baby crawling across the lawn. At the time he was making Anticipation, Brakhage was writing what would remain his primary aesthetic treatise, Metaphors on Vision. The opening phrases of that book are often cited as a kind of statement of purpose regarding Brakhage’s cinema:

“Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of ‘Green’? How many rainbows can light create for the untutored eye? How aware of variations in heat waves can that eye be? Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations of color. Imagine a world before the beginning was the word.”

What is perhaps remarkable about the crawling baby scene in Anticipation is the fact that Brakhage quite literally shows us his theoretical baby, and the unsteady, gestural cinematography seems to function as an objective correlative, or even a direct illustration, of “the untutored eye.” While Brakhage would return to the image of the baby in Dog Star Man, that sequence is altogether more abstract, with a bevy of scratches, paint daubs, light flares, and collage elements dancing across the surface of the film, superimposed over a close-up of a baby’s face, its eyes barely open.

But Anticipation is a film that shows Brakhage working these ideas out in real time, and he has not mastered them quite yet. The single longest sequence in the film, from about minutes 16 to 23, observes a group of children at a carnival at night, whipping in and out of the frame as they ride a tilt-a-whirl. If we look at this sequence as a kind of para-narrative elaboration of Brakhage’s concept of untutored vision, the mechanical pleasures of the ride also represent a kind of existential death for these children. Yes, they are experiencing a scrambled, adventuresome form of vision, as their bodies careen through space. But this perception, which formally mirrors Brakhage’s own camerawork, has been tamed. It is not vision as such, but a zone of child’s play which has been safely cordoned off from the quotidian demands of the tutored eye. Have your psychedelic, nondirective visual experience, it suggests, but understand that such interiorized seeing has its place, and must remain there.

In the second-to-last extended sequence of Anticipation, we return to the camera-stylo gesturalism of the earlier part of the film, but Brakhage takes us to a zoo, where we watch flamingos preening, alternating with similarly unstable scenes of a sleeping child. Based on the lighting and color, we can tell we are back in the house, and following the basic grammar of montage, we sense that Brakhage is offering a comparison between the birds, who exist in a sensual world without language, and the sleeping child, safely enveloped in the interiority of their dreams. This, it seems, is the realm into which Brakhage’s untutored sight is exiled: hypnagogic vision, what we see with our eyes closed, and dreams themselves, physical and mental feedback, kept apart from the nominative world.

In this way, Anticipation of the Night is practically an allegory for the destruction of raw sense phenomena by culture and language. Its echoes of Lacan are worth remarking on, since both men are describing the acculturation process, and the formation of the human subject, as forms of fundamental alienation, occasioned by the subjection of vision to the Gaze, a strict disciplining of the ocular realm. In a way, this film finds Brakhage laying out the problem that he would be exploring throughout his career, but he has not yet found a way to simply embody that crisis through cinema.

Instead, he is telling us a story, one of innocence despoiled and the individual psyche crushed. And Brakhage has still not found a way to be the protagonist of his own vision. He is still performing a facsimile of defeat, and in the final moments of Anticipation, we see Brakhage’s shadow once more, this time swinging from a noose. As uncharacteristically melodramatic as this act may be, perhaps Brakhage had to kill his avatar in order to be reborn as a dual subject, an absolute merging of the camera and the eye.

Comments are closed.