Diane Arbus once described horror as the relationship between sex and death. With the exception of pornography, no other film genre brings us closer to both than horror. Nowhere else in cinema are we so confronted with the unconscious, and what lies in the deepest regions of our mind, than in dreams of sex and the dread of death. Horror brings these fears and fantasies out of the mind and projects them onto a screen. It is, in a way, the most liberated film genre.

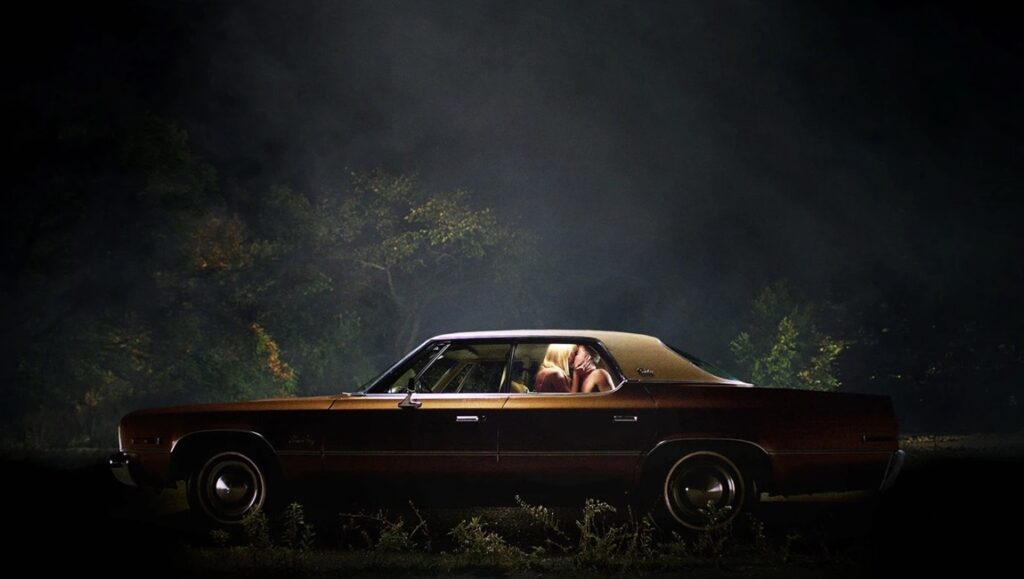

In some films, sexuality is presented subtly, more of a thematic backdrop than a foundational plot point. In It Follows, David Robert Mitchell’s 2014 film that soon celebrates the 10th anniversary of its Cannes premiere, sex houses the entire story. It is the roof, walls, and floor to the film: everywhere the characters look, they are trapped by its expectations. The plot, as with many films of the genre, is ostensibly simple. There is a curse: if you fall victim to it, an embodied person — the embodiment changes: “it can be someone you know, it can be a stranger in a crowd” — follows you. It won’t stop until it catches you, and if it does, you die. How does one fall victim to this curse? By having sex with the person who currently has the curse. How do you pass it on? By having sex with someone else. The film follows Jay (Maika Monroe), a teenage girl, but the number of victims is long and ever-growing. All it takes is a quick fuck for the horror to begin. (A sequel, They Follow, is set to begin shooting later this year.)

It Follows has been widely described as a metaphor for STDs. It’s not hard to see why. Where other films have used sex metaphorically, It Follows condemns sex literally: it is the arena where the central horror is inherited and forwarded. But as metaphorical readings go, this is a frankly literal interpretation. A more compelling view of the film is earned when the curse is seen as the burden of shame and the inheritance of trauma. No one understands these feelings better than teenagers in the microcosm of high school entering the murky waters of sex for the first time. Sex, for the teenager, is defined less by pleasure than by pressure, and once it’s happened, isolation may set in where there should be intimacy. It’s impossible to let go of shame; you might think you’re over it, but it can rear its head again at any time. As with trauma, a theme expressed in the film through Jay’s relationship with her deceased father, it never goes away. We may try to distract ourselves with vices, be they drugs, alcohol, or sex. But our trauma is only buried, not worked through. It follows us forever.

The history of the Western horror film is intertwined with social expectations of sex. The genre’s marriage of sex and horror can most easily be found in the slasher films of the 1970s and ‘80s. The classics of the genre — from Halloween to Friday the 13th — all apply the same rule: the price of sex is your life. (These rules were elaborated on and satirized in Wes Craven’s Scream series: “There are certain rules that one must abide by in order to successfully survive a horror movie. For instance, number one: you can never have sex. Sex equals death, okay?”) It Follows isn’t so much an example of this trend as it is its apotheosis: it literalizes the tropes of the genre and moves them to their extreme. But the horror film has been only too willing to endorse this credence for decades.

Sex and sexuality have accompanied the horror genre from its inception. This isn’t surprising. Fears over bodily abnormalities, moral panics over pleasure, and condemnations of the flesh were all familiar themes of the horror novels of the 19th century. Much of early cinema may have been subject to censorship, but these themes were, even with censorship, impossible to ignore. The vampire movie is an obvious example; its themes of sexuality go back to Stoker’s original novel, and it doesn’t take a massive leap of imagination to connect the seductions and desires of Dracula to sexual desire. The sexuality that drips from the page lands on the many filmic representations of Dracula: Bela Lugosi’s performs Dracula as a Lothario, Christopher Lee as the angry lover.

But overt sexuality wasn’t just the purview of vampires. In Werewolf of London (1935), transfiguration into a therianthropic creature isn’t just a horror in and of itself, but also an expression of sexual rage and jealousy. Wilfrid Glendon (played by Henry Hull), having been transformed, attacks his wife after seeing her walking with her childhood sweetheart. Themes of sexual liberation were carried into John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London (1981), where the werewolf’s attacks are a strong sexual driver: the main character David has no memories of them when he wakes up after a full moon; he is rejuvenated, energized, and — as made clear in his eagerness to carry his girlfriend to bed — ready for action. The violent outbursts of the werewolf, these films suggest, are not simply animalistic expressions of a possessive force, but the liberation of our own primal urges and jealousies. “The werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a Satanic creature with the worst qualities of both,” Dr. Yoagmi explains in Werewolf of London. The beast has human traits after all.

Attitudes towards sex changed after the Second World War, and naturally this was reflected in the cinema. The increasing liberation of sexuality in the home was accompanied on the screen, though naturally, liberation in film does not always mean a liberated politics. From the 1960s onward, the rise of independent filmmakers, coupled with greater economic independence of young people, allowed younger moviegoers to enjoy films made for their demographic; namely, films which took pleasure in gore and sex, disregarding the need to meet parental approval. Sex passed through the generation of filmmakers, from subtler portrayals to unconcealed extravagances that often bordered on the pornographic.

Unsurprisingly, most of Hollywood’s history has been dominated by men and thereby reflects male values. Time and time again, women’s sexualization and suffering have been shown onscreen in films written and directed by men. But sometimes, the male values presented in horror are expressions of male sexual anxiety: fears of inadequacy, body dysmorphia, and a crumbling of masculinity. Taken literally, The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) is just another science fiction fantasy and example of mid-century cinema as camp. After being exposed to radiation and insecticide, Scott Carey’s body starts shrinking smaller and smaller until he reaches subatomic size. The story could be read as a commentary on a brand of masculinity in crisis following the Second World War — perhaps. A more interesting reading is a sexual one: the film embodies the male anxiety of size, echoing Freud’s theory of castration anxiety, wrapped in a science fiction premise. “Didn’t you tell them who you’re married to?” Scott asks his wife at one point. “The incredible Scott Carey, the shrinking freak?”A joke? Maybe. But horror is not always famed for its subtlety.

Freudian fears of castration have been expressed in other films, most literally represented in Teeth (2007). The film taps into a fear that goes back millennia. Dawn O’Keefe plays an abstinent, Christian teenager who discovers that her body is not what she thought: her vagina has teeth that can bite off penises that enter it. Critically dismissed, Teeth is nevertheless interesting insofar as it embodies both body horror and also empowerment from or because of it. The shame of Dawn’s mutated genitalia evolves into sexual agency. Her “vagina dentata” only bites when unwanted sex is forced upon her.

In this way, Teeth taps into a well-worn sub-genre in horror: the rape-revenge film. These films have a so-called liberating message as the persecuted woman extracts her revenge, but only after having endured degradation and violence onscreen — for exactly whose viewing pleasure this is, the jury is still out. There are a number of films that fall into this category, from Last House on the Left (1972) and Lipstick (1976) to, most disturbingly, I Spit on Your Grave (1979), a film still banned in several countries. These films aren’t remembered as milestones in the feminist movement; they were usually written and directed by men and are the worst filmic depictions of female suffering. There are plenty of other films within the subgenre that don’t seek to take pleasure in filming female suffering, and more recently the genre has been tackled by female directors, such as Coralie Fargeat with Revenge (2017) and Jennifer Kent with The Nightingale (2018). But once again, sex is a site of pain and trauma. Sex is a motivation for revenge. Sex equals death.

Can horror be liberating? Let’s take the work of French director Julia Docournau as an example. Two of her recent films, Raw (2016) and Titane (2021), each use the horror genre to interrogate female sexuality and bodies. Raw concerns a teenage girl exploring sexuality through cannibalism; Titane follows a young woman with a titanium plate in her head who has sex with cars. Both films are disturbing and brilliant. Unlike other horror films, Raw and Titane don’t portray sexuality crudely or simply as a way to illicit titillation. Rather, these films are horrific insofar as they explore human feelings. They are often referred to as “body horror” films, but really these films merge genres, showing tenderness in violence and violence in love.

The bedroom is the arena of pleasure and of fear. We are at our most vulnerable during sex. Of course, the horror film takes a voyeuristic interest in sex. The rise of sexual explicitness in the second half of the 20th century was partly due to simple economics. The advertisers were right: sex sells. And box office returns will always trump morality. But the reasons are also psychological. In horror, filmmakers found a natural bedfellow. Horror provides an outburst of violence. Yet in doing so — for all its graphic imagery, misogyny, and sexualization — the genre for decades spawned an inherently conservative ethos: it’s dangerous to be a person with longing. It Follows embodies this ethos to a T. Pleasure is never just pleasure; violence and regret are pleasure’s unfortunate shadows. Sex is the stuff of nightmares, as well as dreams.

Comments are closed.