The inaugural edition of the Los Angeles Festival of Movies closed this past Sunday with the world premiere of Conner O’Malley and Danny Scharar’s outrageous mockumentary Rap World. The buzzy event was attended by numerous local film fixtures and luminaries, and was held at Vidiots, the beloved, newly re-opened theater and video rental store in Eagle Rock. But over in Historic Filipinotown, a much quieter film closed the run of events at the festival’s primary screening space, 2220 Arts + Archives. That was Tana Gilbert Fernández’s Malqueridas, another documentary experiment, albeit one calibrated for a wholly different, more somber and righteous set of effects.

Malqueridas is the result of a staggering amount of work from Gilbert Fernández and editor Javiera Velozo, yet Gilbert Fernández didn’t shoot a single inch of film. The doc was cut together entirely from small fragments of image and video captured in secret by inmates of San Joaquín, the largest women’s prison in Santiago (recording devices are banned within the Chilean prison system). Gilbert Fernández told Cineuropa last May that she “collected more than 4,000 photos and nearly 2,000 videos” that were then poured through, absorbed, and sequenced into a loose narrative. In an effort to curate a kind of material archive of these women’s hidden lives, to create presence where the state has worked to ensure there is only absence, Velozo and Gilbert Fernández hand-printed each frame of the film’s 75 minutes, then re-digitized and re-synced all 32,000+ prints. Carrying this information into Malqueridas results in a stupefying viewing experience. Each wrinkle, light flare, and rough patch of pixels on the various photo scans and vertically-oriented videos make the precarity of the women’s position tangible.

Malqueridas is a radical act of directorial self-effacement. Gilbert Fernández puts the act of image-making in the hands of her subjects — subjects whose very personhood has been eclipsed by the impenetrable battlement of the prison wall. Of course, she, Velozo, and researcher Alejandra Díaz played a critical role when it came to selecting which images, videos, stories, and subjects make the final cut, and in what context. But the film’s script was handed off to her incarcerated collaborators as well. Malqueridas takes an observational approach to the women’s stories, employing a recently emancipated inmate, Karina Sánchez, to narrate all their stories. These stories arrive the same way the images do: through a looping process of translation and transformation. The recurrence of certain memories, situations, and family dynamics make it clear that some “characters” are telling their stories asynchronously and in fragments, but because Sánchez does all the narrating, there’s no way to gain a stable sense of identity. It could be just a few women experience so much hardship; very likely, it’s most of them experiencing the same systemic injustices.

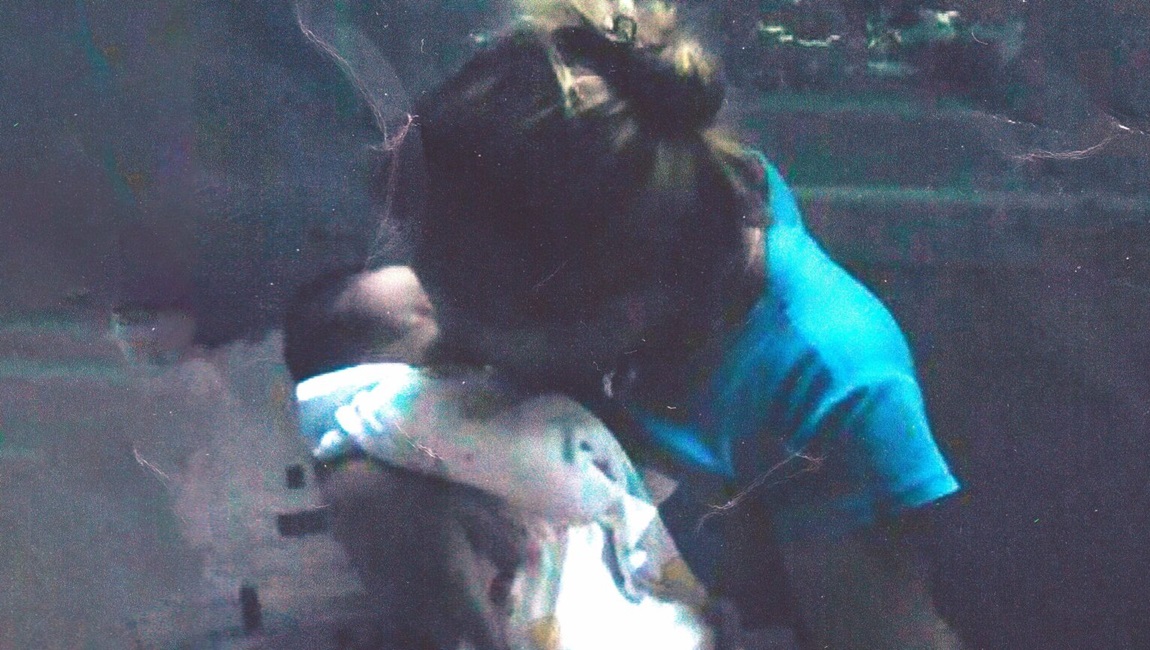

Motherhood is the thread that runs throughout each story, and throughout all of Gilbert Fernández’s work. The film opens with indistinct sounds over a black screen, a pinhole of light slowly forming into something figural. The audio comes into focus first — a baby’s gurgling and a mother’s soothing song. The light clarifies slowly, forcing the eyes in their scramble in their effort to identify the clump of shaded light. The gradual refining of the image nearly animates it; it’s easy to mistake the static image of a mother holding her child for video footage. Gilbert Fernández employs subtle formal manipulations like these to disarm the spectator’s automated process of conventional cinematic image interpretation. The ensuing stories of suffering on the inside of the carceral system, which are redolent in documentary cinema of the past few years, strike the heart with fresh anguish. The women’s search for simple beauty and relief — mewing cats in the yard, mothers on FaceTime asking their children if they’ve done their homework, fireworks cracking off in the distance — “Happy New Year!” one says; “One less year,” says another — are intercut with disturbing testimony of routine neglect and abuse. One woman recalls being chained to a bed during labor and refused painkillers because a guard assumes she’s a “junkie.” Another shares that her children were offloaded by their caretaker, her sister, to the Chilean Child Protective System, because she was “tired of taking care of them.”

On the outside, children are born, they die, fathers leave and stay, life goes on. But life goes on inside the prison too. The clips which turn the camera on social life in the prison depict turbulent activity. The cops raid the cellblock and leave a mess. Posed photos of the women carefully made-up and dressed accompany the cheeky voiceover: “Get ready, were going to be on Facebook! The girls of Ward 5!” One heart-rending scene shot on front-facing video depicts two women snuggling in bed. “I’m watching a movie with my sweetie,” one woman says. The other responds, “It’s very cold in here, but not next to you.” Aside from reconnection with their children, companionship (romantic and otherwise) is a ubiquitous desire. In capturing all of this, Gilbert Fernández has crafted a stirring work of art and a vital political document. Malqueridas is a piece of living testimony that raises the bar for documentarians aiming to capture something essential about the prison system and prison life.