Ancient life was all silence.

In the 19th Century, with the invention of machines, Noise was born.

—Luigi Russolo, The Art of Noise

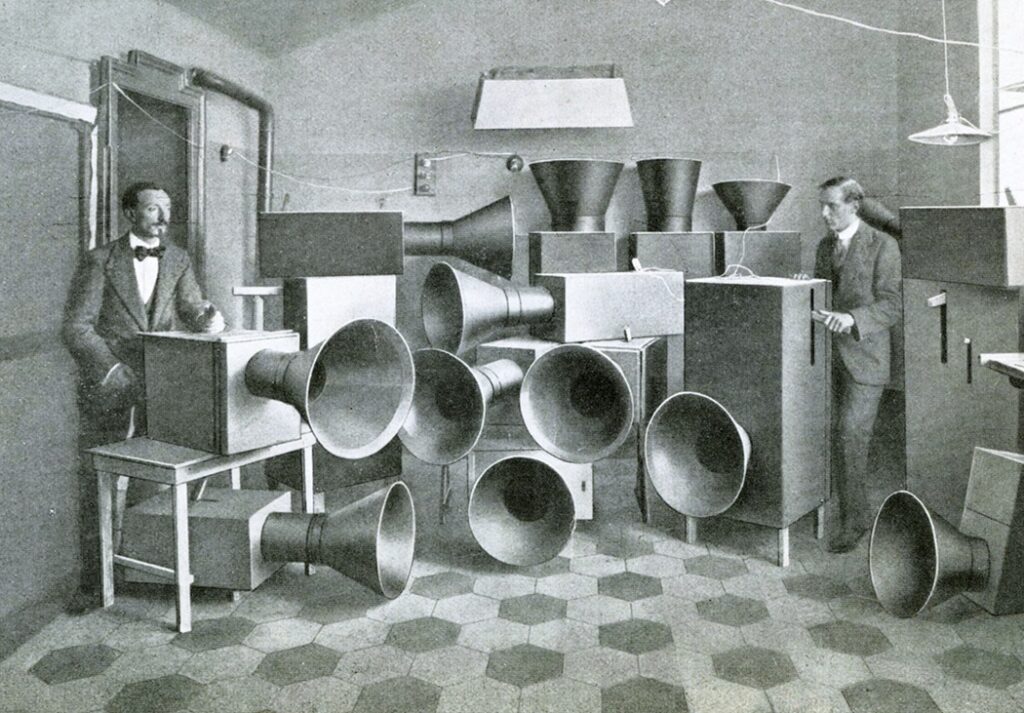

The city Milan in the year 1913. An intrepid wanderer might stumble into a workshop, and find there a multitude of unusual boxes, kitted out with large horns. It’s not clear what purpose these boxes serve, until a bow-tied Italian enters, with spontaneous vigor, and instructs this intrepid wanderer on their use. These contraptions emit a strange, growling noise. The Italian — Luigi Russolo — tells the intrepid wanderer that this is the New Music; that these devices go far beyond the familiar sounds of the woodwinds, the strings, the old percussive instruments. In these boxes is the sound of machines. The New Music, he goes on to say, will not be focused on tonality, nor on rhythm, but it will be the particular quality of sound. The ears of an urbanite have become so accustomed to the industry of noise that the old tones grow tiresome; we are a people in need of new, different sounds. Sound that better encompasses the great spectrum of hearing. Sounds that better reflect the new world. Russolo gestures to the assortment of boxes — the Intonarumori he calls them — and says that people of the future will see these contraptions as the beginning of a new era of sound-production. Russolo tells the intrepid wanderer that he is a lucky man, to be here at the beginning. But then the snag: the intrepid wanderer has come from the future. And he had never heard of Luigi Russolo, nor his squeaking boxes.

In its most foundational aspect, Harmony Korine’s new artistic project resembles that of the Italian Futurists, there in the 1910s. These innovators recognized, in the frame of music, that it was not to be musical structure or arrangement that defined the future of the form, but musical texture. In Russolo’s The Art of Noises, he recognizes that in a world defined by new kinds of urban din, a constant soundscape of undesigned noise, that an audience might find themselves tired by the old-fashioned timbres. He says as much himself: “Beethoven and Wagner have stirred our nerves and hearts for many years. Now we have had enough of them; and we delight much more in combining in our thoughts the noises of trams, of automobile engines, of carriages and brawling crowds, than in hearing again the ‘Eroica’ or the ‘Pastorale.'” It is not a question of re-envisioning the grammar of music — as Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and a host of others were attempting — but rather changing the quality of the sound. Some attempt to break music from its ancient continuity, and shock it into the now. A similar ring is heard in Korine’s bristling Variety interview: “I’ll see a clip on TikTok that is so inexplicable, so outside the realm of what I even imagine someone creating. Like, I can have an experience with a 30-second clip that goes so far beyond [what movies do for me].” It’s to TikTok and to video games that Korine has been consistently pointing in his press run for AGGRO DR1FT; here is a conscious attempt to break with the tradition of conventional filmmaking and find something else. But that something else is specifically not found in the increasingly high-up, far-out methods of the arthouse or the experimental filmmaker. Korine is fascinated with the now; with the ephemera constantly buzzing through phones, laptops, game consoles. In that same interview, Korine goes on to state: “Video games are so advanced and so much more interesting than normal films, I could be sitting there playing a video game for days, whereas it’s hard for me to make it through any of these films.” In this disappointment we can again sense some of Russolo: “Our ear is not satisfied [with the old music] and calls for ever greater acoustical emotions.”

But it is of some significance that Russolo’s instruments, and Russolo’s music, are not remembered outside the cadre of artists and musicologists who venerate his movement. While he did, accurately, predict the shape of music to come — which is now composed of an infinite variety of synthesized and recorded sound far beyond the range of the voice and the orchestra — his was only an initial provocation. His music was an inarticulate beginning, a testing ground for new tools, in which the nature of the tool seemed more fascinating than exactly what it was producing. AGGRO DR1FT might be described in similar terms. The film is most remarkable for its method of capture: the entire thing is shot with thermal cameras, which — after being run through 3D imaging software — renders the entire film in a semi-digital haze of yellows, reds, blues; as though the constant sunsets of Korine’s The Beach Bum had spilled into the camera itself. Here is a neon Miami, in which characters wade through color, themselves silhouettes, recognized by superficial markers: the wraparound sunglasses of Jordi Mollà’s Bo; the box braids of Travis Scott’s Zion; or the lustrously bald head of archdemon Toto. We are abstracted from the actors’ performances; we recognize these people as pegs, as symbols, rather than as fully formed human beings. So much of the film operates on a similarly vague register. We might attempt a gloss of the narrative, which is expressed so obscurely that almost every critic seems to have an entirely different understanding of the film’s plot. In the view of this critic: the film follows Bo, a master assassin, who is at odds with his work. He is tasked with killing Toto, presumably some rival crime lord to his employer. Before doing so, he meets with Zion, who might be his apprentice; the two of them speak equivocally about Julius Caesar and betrayal. A forked tongue slithers from Zion’s mouth, but it is Bo who turns traitor: he rebels against his employer and, in the name of Total Justice, fulfills his final contract as a moral obligation rather than financial exchange. A wife and family await him at home: all he does, he does for them. A familiar-sounding arc, however challenging it is to grasp in the moment. Korine takes his archetypes, and situates them in an archetypal story; AGGRO DR1FT is designed to shed character, and shed narrative. It is the remaining effect that interests Korine.

Which brings his film to an unusual shore. Much has been mumbled regarding the video game influences of AGGRO DR1FT. Often is Grand Theft Auto the go-to comparison, but this selection seems to belie a misunderstanding of how Grand Theft Auto looks, feels, plays. While both AGGRO DR1FT and GTA share a gangland setting, and a generally vulgar sense of humor, it is there that the similarities promptly end. In aesthetic terms, the film has more in common with the likes of DOOM, or Diablo, with red-strewn palettes and a profusion of demonic imagery. While there is a sense of the video game aesthetic in AGGRO DR1FT, it would be inaccurate to marry it specifically to any one title. Rather than Grand Theft Auto, it would be fair to place AGGRO DR1FT much closer to the twirling-era films of Terrence Malick, a director who has affected a not inconsiderable influence throughout Korine’s career. Indeed, Korine and Malick might represent cinema’s oddest couple: Korine recently revealed that Malick has written him a script, and it was only this that could tempt him back to “conventional” filmmaking. Like Malick’s middle period, Korine also eschewed a traditional script for AGGRO DR1FT; like Malick, he arranges his film as an overlapping series of voiceover monologues; he cuts narrative presence so profoundly as to render a film with an arc but without a story; and he positions a protagonist who will reject nature (the infinite kill-cycle of video-game Miami) and seek grace (the wife and the kids; not so far from a traditional Malick finale). But to pair these filmmakers is also to recognize their polarity: Malick chases the sublime, and Korine the ridiculous. In Malick’s middle films, scenes of debauch are often weirdly stilted, or aesthetically inert; Korine is excellent at authentic dissipation, but himself struggles in reaching the higher impulses. AGGRO DR1FT’s improvised dialogue proves as much: these characters can do nothing but repeat aphorisms, so curtly stated as to find banality in every instance. This critic does not think this is a nihilistic film as so many critics have labeled it, nor an ironic one. Funny, vulgar, and ridiculous — yes. But not ironic. This is an earnest film, wearing a fluorescent dress.

Again, we ought to consider the detail of this dress: it’s here that Korine leverages artificial intelligence to coat his phosphorescent images with tessellating patterns, with snaking lines and shapes. The use of artificial intelligence in mainstream cinema is still burgeoning, and still highly controversial. Most recently was Last Night with the Devil doused in boiling water for the practice, in which an otherwise dutiful recreation of a 1970s televisual aesthetic was marred by the inclusion of seemingly random AI-generated cutaways. This was a clash of artistic styles: this was not AI representing AI, but AI masquerading as human endeavor. This is the AI the unions are so keen to quash. But what Korine does is different. He describes AI as “like another type of paintbrush”; in AGGRO DR1FT, AI is not a hidden workhorse, but out in the open. Those swirling, changing patterns that so often deck the characters in closeups are a signature of AI generation; they are a texture that specifically comes from and defines an AI-made image. Again we can return to Rossolo’s manifesto: “[The] evolution of music is comparable to the multiplication of machines, which everywhere collaborate with man.” Korine is leaning into the new textures of the world: into the overwhelmingly digital, the overwhelmingly generative; AGGRO DR1FT is as much a film about some assassin coming to terms with morality as it is a film about the new kinds of images, those we make and those invented by the images themselves, at which point the role of “director” seems to fade into a middle-distance. Korine even seems to concede this fact, crediting his role with a simple “by.” So much of AGGRO DR1FT seems to bleed in from the outer world; it’s a foundational statement on a changing image-culture, positioned within a supposedly moribund cinema. The film could ape Godard’s Weekend, with its final FIN DE CINEMA.

But we must return to the room, the forgotten room, with the unusual array of boxes, decked with funnels. A forgotten room and a forgotten music. Why were the futurists forgotten? Not for the failure of their ideas, but rather for the limpness of their product. For as much as we can vigorously leaf through The Art of Noise, listening to said art is an activity that requires a furrowed brow and a scratched chin. Much the same can be observed of AGGRO DR1FT, a film that is so taken up with reinventing the process of image-making that it often finds precious little to do with the images that it does make. There is a general, often puerile thrill to the motion of the film — a sort of contemplative pulp — but with this is also a feeling of inertia. Being so abstracted from the “narrative,” from what these characters might represent, even from set pieces (this film spends a lot of time between things), Korine somehow achieves a pumped-up genre film that makes 80 minutes feel like an indulgently long time. This is a movie that staggers and sways. It is often fascinating, and it is often — at exactly the same instant — not fascinating. Harmony Korine has identified a problem, and found a solution; but this film is not the revolution it wants to be.

DIRECTOR: Harmony Korine; CAST: Joshua Tilley, Jordi Mollà, Travis Scott, Devon James; DISTRIBUTOR: EDGLRD; IN THEATERS: May 10; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 20 min.

![AGGRO DR1FT — Harmony Korine [Review]](https://inreviewonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Travis-Scott-Aggro-Dr1ft-1024x579.jpg)

Comments are closed.