Imagine being seated for a program of experimental films at a prestigious film festival. The room is packed with people who are willing to watch plenty of films that may ask for complete silence or an inconvenient chunk of one’s time. There could be a clever formal experiment here, a hastily cobbled record of one’s vacation in Crete there, but the audience — a group of people willing to pay money for a lot of 16mm footage of flowers — is typically willing to give everything a chance. Reverent attention is nice, but mere reverent attention is the attitude of the business presentation and the classroom lecture. Shouldn’t art pride itself on asking for more?

It’s always a relief, then, to laugh along with this otherwise monk-like audience when a film by John Smith plays. His humor sometimes comes across as structural stand-up, such as the director-narrator of The Girl Chewing Gum [1976] who asks a building to “come closer” as the camera zooms in, but much of it is found in his clever wordplay. It could only be John Smith who’d realize that T. S. Eliot is an anagram of “toilets” and subsequently film a reading of The Waste Land [1999] in the men’s room to get to that punchline. Even his films that aren’t immediately asking for laughs still opt for the rhythm of humor, such as the wonky walking of Worst Case Scenario [2003] or the cartoonish dance of apartment lights in Citadel [2000]. Far from being mere comic relief, these films are only funny because they’re also formally inventive. Many times the camera movement or framing is the joke, such as Gargantuan’s [2001] one-minute zoom-out of a lizard that features Smith using a string of words to comment on his stature as he appears smaller and smaller. And, with his two Hackney Marshes [1977 & 1978)] films that use the match cut to highlight the decorative differences in uniformly designed tower block apartments, Smith may be the first person to dance about architecture.

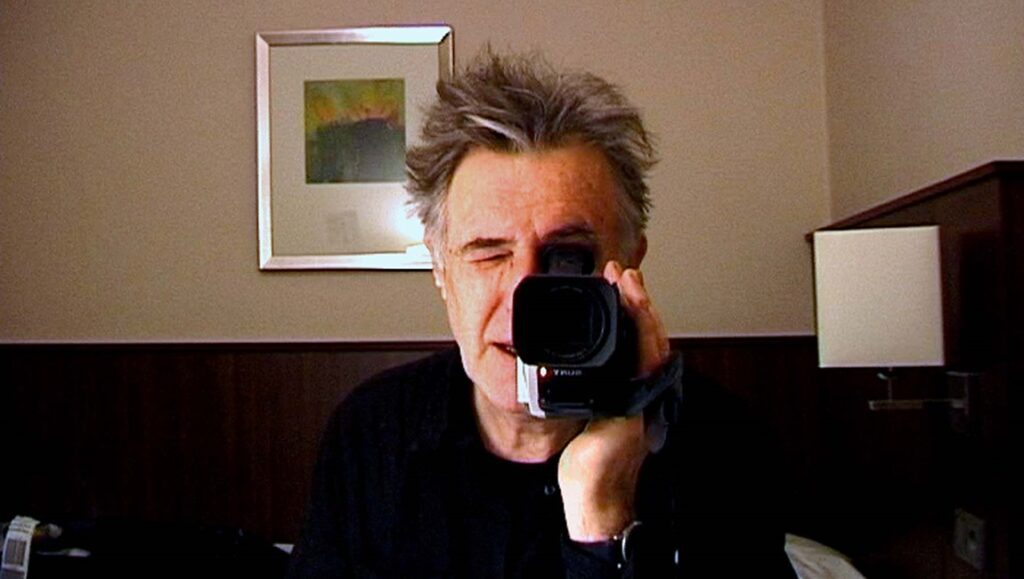

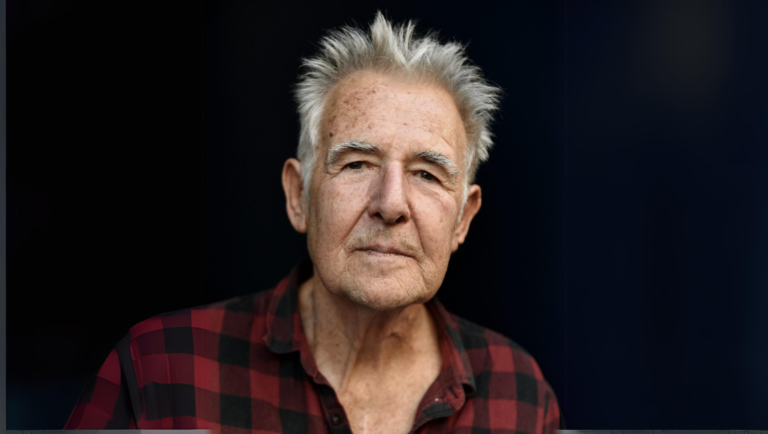

His latest, Being John Smith, tackles what may seem like an inevitable subject for the pun-forward wordsmith: his name. But, of course, in classic Smith fashion, the “being” of the title simultaneously promises something of an autobiography, and, sure enough, the film catalogs a life in the arts with the English language’s most common name. His classmates thought he may have died when the death of the Labour Party’s John Smith inspired incredibly generic headlines, nearly everyone in the art world suggested he adopt a pseudonym, and the Internet has doomed those searching for the clever artist by offering stills of the golden-locked love interest of Disney’s Pocahontas instead. A third “being” is also at work here — being John Smith right now. In a parallel narrative to the voiceover autobiography, Smith, in silent text on the screen, worries this film won’t be celebrated like his earlier work and that his voice is giving out because of his chemo treatments. Of course, it’s still pretty funny.

Since Being John Smith invites such a reflection, I spoke to the legendary English filmmaker about his half-century-long career.

Z.W. Lewis: Many of your films point out fun coincidences, so I’d also like to point one out. You’re the exact same age as my father. And you mentioned in Being John Smith that you got kicked out of school for having long hair at the age of 17. Meanwhile, in Mississippi, my dad, who was in a band at the time, also got kicked out of school for his long hair at the age of 17. So it must have been the same year. I’m wondering if you could expand upon your relationship to your long hair at the time and your school’s relationship to your long hair at the time, because that might say something about that time in your life.

John Smith: That time was, as you know, the late ’60s. There was quite a lot going on with youth at that time, not least to do with everybody going to San Francisco [laughs]. Yeah, my parents couldn’t cope with me, many of my friends’ parents couldn’t cope with them, just because we were the kind of more or less the first generation to really answer their parents back. And, basically, we thought we knew it all. We were going to make the world a better place when peace and love took over.

We just had no respect for the schools that were indoctrinating us with all what we saw to be very conservative information — which was very conservative information. I really hated my school. I was really glad to be able to make this film, which in many ways was quite cathartic, not least that I could actually say how much I hated my fucking school. As I say in the film, when I was at junior school, I really liked learning. I was at the top of the class when I went to my senior school. I talk about getting shorter and not growing and being bullied, but one of the main reasons I never succeeded in my senior school was we were never told that, all of a sudden, learning wasn’t supposed to be enjoyable anymore. It was a task that you had to do.

So we had these very severe teachers who, you’d never see a smile on their face from one week to the next. And there was a lot of discipline, so you couldn’t do anything else but rebel in that situation really, or I felt that, obviously not everybody did, but a fair number. And I was very happy to get thrown out of school because I’d wanted to leave school. My parents were very disappointed with me because academically I’d been very good when I was younger. I’d been really into chemistry. The reason I was actually into chemistry was I really liked making explosives, but my parents didn’t know that. So they had thoughts about me going off to university and becoming a scientist of some kind. After I started rebelling at school, along with getting interested in art, I decided I wanted to go to art school; but I was only 17 at the time. It meant I couldn’t have got any funding, couldn’t have got a grant until 18.

So I was dependent on my parents, and my parents said: “We’re not going to let you go to art school, we still want you to go to university.” So, fortunately when I got thrown out of school, there was no way I was going to go to university. So my parents reluctantly said, “Okay, we’ll still support you to go to art school.”

But that only happened for a couple of months because almost immediately when I went to art school, I left home, moved into a squat with my girlfriend, and started dealing marijuana basically to survive until I had a grant the following year. That’s part of the story [laughs].

ZL: This is — perhaps unsurprisingly, given the title of this movie — one of the more confessional of your works. You’re sometimes confessional in a lot of your movies, but, especially in terms of the self-deprecation and kind of autocritique in the text-based narrative, it seems a little bit more serious this time than something like in Shepherd’s Delight [1984], for example. Was this something that you felt in the process of making the film, or is the film the result of feeling this way?

JS: It was a very organic process, actually. There is self-deprecation and hopefully some discomfort in the other films, like Shepherd’s Delight, maybe things in Hotel Diaries [2001-2007] and Unusual Red Cardigan [2011]. But I agree, in this one I go further than I’ve gone before; but it was, just as I said a minute ago, that it was quite a cathartic process making the film.

I didn’t really think about it too much, except that, as I say in quite an early caption in the film, “I’m worried this film might end up being too conventional.” And these were the things I was thinking at the time, thinking, “Oh, what’s going on here? I’m just telling a story, a life story.” So I wrote this might be too conventional, and then I very quickly just said I’m worried it might lack the wit and formal ingenuity of my earlier work, just as a stream of consciousness in writing.

All of the things I say in the film, they’re basically truth, though they might be exaggerated. I really did go to school with William Shakespeare Smith. A lot of people think I made that bit up. [laughs] Yeah, I have maybe a kind of confessional Tourette’s. I can’t stop myself sometimes from saying things which should really embarrass me. Ever since that bit in Shepherd’s Delight — little did I know that I would have a drinking problem later, but at the time I didn’t. [laughs]

What one wants people to do is wonder: “Is this true?” I never want people to just consume what I’m saying. I want them to have some kind of doubt about it, but hopefully more or less believe it.

ZL: I found it interesting because whenever I’m reflecting on your older works as a viewer, I have this great distance from it, while you must have a completely different relationship. I’m curious if you’re familiar with this term “late style.” It’s been having this big resurgence online.

JS: No, I don’t know it.

ZL: It basically refers to what you’re saying. A lot of artists are typically better known for the works they do earlier on in their life, but then this makes the later works that aren’t as canonized more interesting or idiosyncratic. They deviate from what you would expect from the artists. I’m curious if a term like that holds any meaning for you as an artist, or if that’s something that just us critics and observers find useful.

JS: I’m very aware that I’m a little bit of a coward in terms of what work of mine that I show. I still show lots of very early work going right back to The Girl Chewing Gum [1976] and even before that. But I’m very aware nowadays that I’m more concerned about the audience than I used to be. I annoy myself to some degree, and I sometimes think I’m not going to take a risk on that because people might find it a bit dull. Because when I first started — I don’t know how much you know about my very early work. You probably won’t have seen much of it because it’s not available online, but I was making very formal structural film when I started off.

I quite quickly started using words and things, but a lot of my earlier films don’t have any narrative element to them, they don’t have any words, they’re all to do with images and formal structure based around ideas to do with form and materialism. And to cut a long story short, some of them are pretty hard going. In fact, I look at one or two of them now and I don’t really understand what I was trying to do in that film [laughs]. But, that being said, the main problem with showing the older work also is that if you do a screening, you’ve only got a certain amount of time and I do many screenings that are compilations of my films.

And if I’m just showing one program of my films, especially if they’re short films together, I don’t want to show more than an absolute maximum of an hour and a half because it’s just too much for people to take in. The things that are harder or longer go by the wayside a lot of the time. But two years ago I did what I ended up calling an “introspective” of my films in London, at two cinemas, the ICA and the Close-Up in East London. I was asked to show everything I’d ever made by Stanley Schtinter. And I said, “I’m sorry, but I could not bear to show everything I ever made, but I’m really happy to have the opportunity to show a lot of stuff.”

That was two years ago. In 2022, it so happened that I’d been making films for, to my horror, 50 years that year. So I had the only marketing idea of my life that I’ve ever had and I said, “why don’t we make it 50 films made over 50 years?” I did 10 programs of films over 10 weeks. Each week, I showed different films chronologically. And I was really pleased because I ended up showing these films that I would not normally show. And not only did I not feel embarrassed about them, but other people enjoyed them. And, of course, a lot of people were very interested to see them because they hadn’t seen that aspect of my work at all.

But it is really curious, the thing of looking back, because I’m looking back all the time because I show up in the work and because I’m often in the films, very often in voiceover and occasionally visually. So I have this really weird kind of experience of going back in time every time I show a program of my films. And it’s interesting listening to my 23-year-old voice in The Girl Chewing Gum; it’s very different from the voice I have now, hardened by decades of cigarettes and whiskey, as I like to say. And I wonder whether one thinks about mortality more because of that. Or less, maybe, I don’t know, maybe you’re immortal. You think, okay, I’m still present as this 23-year-old person in the world [laughs].

ZL: It sounds very interesting because it sounds like your version of the filmography and the works of John Smith are the ones that you’ve probably seen the most often. And there are the ones that are under the constraints of programming. Whereas we who have more distance like critics or writers may try to find a narrative for your whole filmography. But for you, it’s what has been programmed and what you see very often.

JS: Yeah, but I’m more guilty than anyone of what’s seen and what’s programmed. When I made The Girl Chewing Gum, it wasn’t at all popular. I thought it was pretty damn good. So I kept showing it. And after a couple of years, it did become popular, but it could have just vanished into nowhere. No, it’s interesting. I sometimes wonder if I would still be making films now if I hadn’t made a couple of these films which became fairly iconic quite early on. Yeah, I think we shape how we are seen in many ways.

ZL: It’s also not really a surprise that since your works usually deal with words and playful language that you’d give special attention to names. It struck me that while language is this thing that dictates our thinking, names might be the most powerful form of language.

Like power left over from the days of incantations and spells where you have to name the object or like in Genesis, Adam naming the animals, or names that we make up to understand the world like late style or political names like Palestine or your focus on your father’s middle name, Lyle. Are you cognizant of that kind of power in your art process, even if it’s just in selecting the title of the work?

JS: Yeah. Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. As I say in the film, I’m aware of it in personal terms. Literally, more or less every day — this really does happen — that if I speak to somebody who doesn’t know me, they might make a joke about my name immediately and say, “Oh, like the beer [John Smith’s], so you make the beer,” or all this sort of stuff.

And then I’m like, oh, fuck off [laughs]. So I have to preempt that. But yeah, I think outside of one’s own self, I think we do attach significance to names. I’m very curious. I find it slightly irritating, but there are many visual artists who have really weird names. And very often they make them up themselves, or they deliberately elaborate them, of course, in order to be memorable or interesting. I sometimes talk to people about my name and they say, “your name is really memorable.” I guess the only thing is, it’s very unlikely that there are any other artists called John Smith because they’ve all changed the name.

There is a folk singer, actually, in the UK, that I’ve discovered called John Smith. So if you look up “John Smith artist,” you’ll get him as well as me. I was thinking of using his music for my film; I bought his CD. Got an autographed copy [laughs].

ZL: Is he any good?

JS: It’s all right. It was a bit mediocre, but there was nothing offensive about it. It was a bit like being John Smith: a bit ordinary.

ZL: You point out that a lot of people do think that you’re using a pseudonym. And I think that’s interesting because maybe what that might imply is that they’re thinking that there’s such maybe like an Englishness to it, right? That you’re making a purposeful statement on the history of England with your work or your career or your persona if you were using such a pseudonym.

JS: Yeah, definitely. I mean I hinted in the film that I wonder whether it affects the kind of work that I do, which makes my name appropriate. Because my work has to do with the mundane world, it’s not about the drama. The narrators are unreliable in the films, so you’re never quite sure whether you’re being told the truth or not. And I think that’s probably one of the reasons that people sometimes think that it’s not my real name. But also it may well be part of the reason why I make work like that. I’m making work to fit my name; as we know, it’s so common for Mr. Fang to go on and become a dentist or it’s very common for names to reference professions going back to their origins. I hope that I’m a smith and I hope that I craft things, but I guess I’m crafting John in my own film.

As for titles: I really have to think about naming the title for the film, largely because of the Internet, right? For example, I made an installation a few years ago, and I called it Horizon [2012]. And I thought, that’s just hopeless for a Google search. So I deliberately nearly always try to have a title that is peculiar. So I ended up actually calling the film Horizon (Five Pounds a Belgian) because it was a little line you heard somebody speaking three quarters of the way through the film as they passed by behind the camera.

So, of course, that is something one thinks about all the time. I wasn’t sure about [the title of] Being John Smith, but just in case it doesn’t seem to lead you to Being John Malkovich or something, it’s quite handy.

[John takes a phone call and we briefly commiserate with each other about using Zoom]

ZL: I had to teach on Zoom whenever the pandemic started, and yeah, that was quite an ordeal — the delays and about 20 minutes worth of technical difficulties before the class starts and various things like that. But I eventually got used to it as well.

JS: I did a weird thing a few years ago. I think it was a class I was teaching on Zoom for somebody else at an art school somewhere, and they were showing my films. At the time, you couldn’t really show films as part of the Zoom or whatever it was. So what they were doing was, we were pausing my lecture and then they were shown the films. So when they paused the lecture, all I could see were all those people watching the film.

And so I’d see 20 faces who were watching the film. There was a bit of yawning [laughs]. I’d love to have been able to record it. Ethically, it wouldn’t have been very good, but it was really interesting just watching all these different private audiences and their own attention or lack of attention.

ZL: Reacting to John Smith?

JS: I was thinking about this because I’ve only shown the new film a few times. I’ve just done three different festival screenings with it. And I’ve really been thinking about — one of those things I quite like in my films is the fact that my films have humor and that you get reactions. So you can tell if somebody’s reacting to the work. But with this film, I found it odd because I usually correctly anticipate the places where things that people will laugh at, but I underestimated the kind of reverence with which people treat cancer. Because I think one of the funniest things in the film is when, say, I do this really heavy thing, and then I say, “I now have a perpetually dry mouth matching my dry sense of humor,” because my salivary glands have been fucked up by the radiotherapy. And no one laughs at that at all [laughs]. Maybe they would if I wasn’t in the room.

ZL: I noticed this film included a lot of archival material, more so than a lot of your previous works. I’m very surprised you kept a report card, for example. I’m curious if this affected the editing process for you, considering that a still image doesn’t have quite the same rhythm as a moving one.

JS: Almost all of those images come from my family. When my father died 17 years ago, I ended up being the executor of all of his possessions. And I was shocked and fascinated to discover that he’d kept all of my school reports going through from when I was five up until I was 17 when I got thrown out of school. So I have the whole sequence of these reports going up to the last one, which I would have liked to have included because I remember I did really make an effort. During the last year I wanted to get qualifications, and I thought I’d done much better than the school thought that I had.

So the last report was much worse than I thought it was going to be. And what happened with school reports is you weren’t allowed to open them. You’d bring them home, and my parents would open it and look at this thing and go, [gravely] “what have you been doing?” And I was really insulted by this; I thought I’d been really treated very badly by the school. So I snatched the report off of my father and tore it into pieces. So the last one is sellotaped back together [laughs]. But it was all filed in a ring binder, all of these reports showing my slow decline academically, which is quite interesting given that I ended up as a professor with a PhD.

Anyway, that’s a whole other film. I could have made it a feature length film, but I thought it might be a bit too much. So there’s a lot more. I’m thinking of something that’s happened since that I might make as a kind of epilogue. I haven’t decided because I do like the ending.

ZL: I think this gets to the worry at the beginning of your film, that it’s going to be too conventional, right? That it’s going to be a voiceover with archival footage and mostly still images. Did you conquer that worry?

JS: I started off with this film much more conventionally, because usually most of my work grows organically. It usually grows, I shoot a bit of stuff, then I edit it. And that suggests other things, and I don’t really know where the film’s going. Whereas this film started with the last shot of the concert, the Pulp concert, because I shot that image intending to do something completely different with it.

I was originally going to make a film which was quite abstract. I was going to superimpose that image on top of itself many times. So you just had this kind of bubbling kind of image that you wouldn’t even be aware it was people. And I was going to do the same with the sound, so you had all this noise. And I was going to strip the layers away until it gradually revealed what the original source was. But I tried, did some tests for that, and it just didn’t work. But I loved this shot, I really wanted to use it. And that was the impetus to actually make the film, because I had been intending to make a film about my name for decades, but I hadn’t got around to it.

But I just thought, all these people singing “Common People,” it’s a celebration. Celebration of common people is a perfect ending for a film about being John Smith. I then wrote a text and was very surprised to discover how quickly that developed. It was more or less a stream of consciousness, the whole thing.

I wrote most of the original script in two or three days, and it just spilled out. Then I had this text and I simply recorded the text and then decided I knew I wanted to have images in the film, but I knew I was going to have a big hole to fill.

But having made films like The Black Tower [1987], I actually really like having no image on the screen and just sound in places. I wasn’t intimidated about the fact that I wasn’t going to find images for everything. But yeah, obviously one’s thinking about rhythm all the time, but I like working with still images; there’s less decision-making. Duration is completely flexible; it’s not to do with any action. So you can really play with whether something flashes up for a few frames or whether it’s there for a minute.

I don’t think of it any differently from if I were using moving images, just in terms of the pacing of the film. And also, in many of my films there’s so little movement in them anyway. In The Black Tower, there’s hardly any action. We’re looking at shots of architecture most of the time, nothing happening.

I mean, [in Being John Smith] that image of my great grandfather stays on the screen for probably a minute and a half, you know. But there are changing captions, so we have different ways of keeping momentum. I’m very pleased with the pacing of it. It seems to kind of roll along quite rapidly. Very often people say to me, “I can’t believe it was 27 minutes; I thought it was shorter,” which is always a nice sign.

On that note, the first of my Hotel Diaries videos is just shot in the hotel room in Cork, and I’m just looking at a frozen image on the TV screen. When I first made it, I sent it to the Cork Film Festival, so obviously a good place to premiere it. I got cold feet about it, thinking it was too long. So it was 11 minutes long and I cut five minutes off of it. Now, I got them to agree to showing the six-minute version. But then the festival director got onto me and said, “Why did you cut it down to six minutes? 11 minutes is better.” So I said, “All right. Fine. Show the 11 minutes. But it was in the catalog at 6 minutes. So I think it’s very slow moving, and I got this great review saying, “John Smith makes 6 minutes feel like a lifetime.” [laughs]

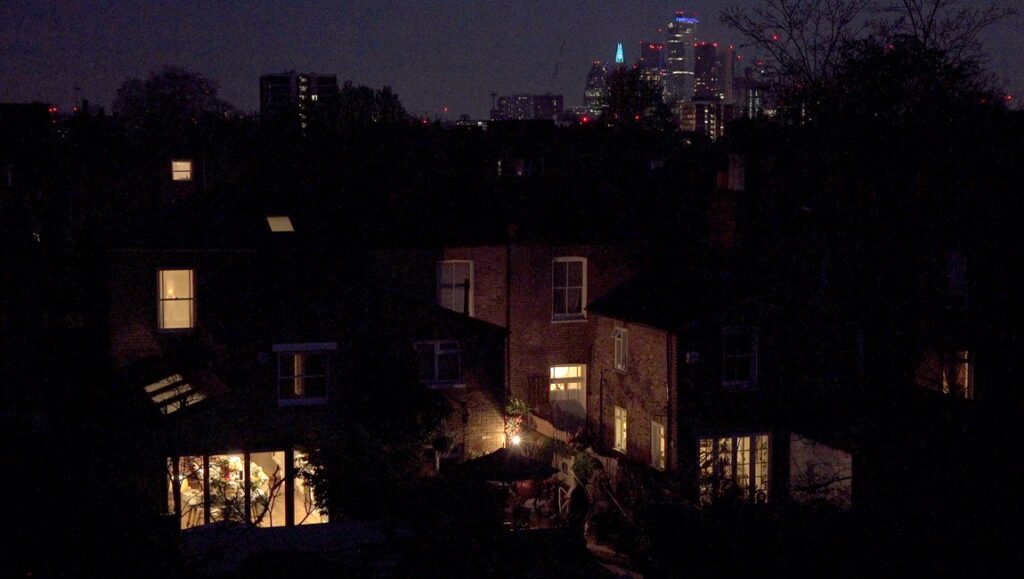

ZL: After marathoning your films yesterday, one thing that kind of struck me is that it’s kind of like, if we’re using this time to reflect on your career, this history of London during your time. And not in a way that a tourist like me sees it, but like Hackney Marshes [1978], The Black Tower, Slow Glass [1991], Blight [1998], Home Suite [1994], Lost Sound [2001], Citadel [2020] — this is all about the developing history of London and a particular kind of neighborhood of London.

Was shooting around this a matter of means of access? Or were you having a particular interest in this particular neighborhood as well?

JS: It’s the place where I live. It is right around me, and I prefer if at all possible to make work about situations and places that I’m familiar with. So it’s just natural that work actually happens around where I live. I mean, there are exceptions to that. Of course, I have Hotel Diaries, but they’re made in the place where I’m living for a short period. And even Flag Mountain [2010], which is shot from a balcony in Nicosia, was filmed from the balcony of an apartment I happened to be staying in.

I guess all the subject matter of a film comes out of things that I see, nearly always. So very often I’ll see things in my immediate environment, and I don’t make the work straight away. Usually the work is not spontaneous. So it means that it’s much easier for me if I see something near me to actually go back and revisit it when I’ve sort of thought about it some more.

But it’s also to do with familiarity. I would never have made The Black Tower or thought of making The Black Tower if it wasn’t a building that I could see from the bedroom window of my house every day. So I noticed that the light was changing on it, so it looked like this hole cut out of the sky, which is completely to do with my own experience.

But I’m fascinated by the way in which these films, which are always to do with the present, over a period of 50 years, turn into a chronology, into historical documentation. I mean, not least The Girl Chewing Gum. I still live literally five minutes walk from where that film was shot. I’ve moved around a bit since, but I happen to be almost where I was living at the same time when I made that film. And that location is part of London that has become so gentrified now. And if you look at The Girl Chewing Gum, I mean, it really looks like a poor working class neighborhood, which it predominantly was. So, that film was all about the present. I deliberately wanted to look at the most mundane environment that one could imagine. And, of course, nearly 50 years later, it’s exotic, you know. It looks like these people are like actors in a costume drama.

And I actually made a remake of that in 2011 [The Man Phoning Mum], where I’ve re-filmed the same scene from the same camera position. The glass merchants had turned into a motor scooter shop. The cinema had been demolished to make an apartment building here. So, fortunately, the architecture of the main building that you see is more or less the same. So you can recognize that it’s the same place. And I took the original footage and put it on my mobile phone and strapped that to the LCD viewfinder of my HD video camera so I could follow the camera movements of the original film, and sort of, as best as I could, match what was going on in the original film. And then I superimposed one on top of the other. So you get these kind of ghostly, grainy, black-and-white people from 1976 meeting up with very colorful, high-definition people from 2011. As they’re superimposed on each other, they kind of meet. And I had this thought that maybe the girl chewing gum still lives in the area and she happens to be walking by and walks past her former self, but I don’t know whether that’s actually true as I wouldn’t recognize her now [laughs].

I am very interested in the way in which things become records. And they get programmed in that sort of way quite often in the context of architecture. The Architecture Association did a program called “John Smith’s London” a few years ago. But that thing with time is very curious. I really wonder if my perception of time is kind of colored by the fact that I show my films a lot, and I actually like to be there, and I like to do Q&As, I like to hear the reactions of audiences. So, you know, at least 10 times a year, I kind of see this city where I watch this history of myself and my environment.

ZL: Well, speaking of recording a time and recording a location, as you mentioned earlier, it was equally bizarre to watch Hotel Diaries after living through the news with Israel and Palestine. I read a London Review of Books article about the assassination of Nasrallah, right before watching your film about [Yasser] Arafat, so it was interesting to see that kind of rhyming.

I’m curious if you’re interested in continuing that series or if you see the Hotel Diaries series as being very much part of the Bush-Blair era and leaving it to that.

JS: Well, of course it’s tempting to go back to it. I mean, I stopped it because I just didn’t want to carry on doing it until Armageddon, because it’s just depressing. I kind of left it at a point where I wanted to be optimistic about the future.

But I have thought about going back to it. I mean, I like showing them now because in many ways, nothing changes as we know, and partly because, you know, half the fucking media talk about Israel-Palestine as if the world began on October 7th last year. That kind of, “how could they possibly do this horrific attack?” There’s plenty of explanation and backstory to that as we know. However, how much that work will get shown now, I don’t know.

I mean, it’s interesting because I’m going to Leipzig next week and I’m showing the film at the DOK Leipzig festival. I’ll be interested to see if I get any reaction to the mention of genocide in the new film. I think it’s more or less illegal to mention genocide in Germany now, other than the Nazi one.

I find it interesting that I used to get shown in Germany more than any other country in the art world. And it’s pretty much the same in the cinema world as well. But not so much in recent years. I suspect it might be because of my political stance on Israel/Palestine. We hear about things that are happening to people behind the scenes, with art collectors contacting commercial galleries, saying that they’re not going to work with them anymore unless they disown this or that person. This really is McCarthyism appearing. But I don’t need to lecture you about that. It’s just pretty up front in my consciousness.

Comments are closed.