‘Tis the season of list compilation. All through the land are lists being compiled: the annual effort to determine the canon of Christmas Movie restarts its industry. Dark smoke plumes above factories of journalists, each in mind to produce a masterpiece of list production. Christmas has ever been a time of lists. Though in this great throng of publication is also an ironic undercurrent. For every list that attempts, in earnest, to trace a canon of unambiguous Christmas films, there is another that trades in technicalities. Die Hard, a summer blockbuster that happens to take place at Christmas, is the herald of this counter-movement, by which any film that can be conceived within a Christmas context is automatically eligible for Christmas status. Films like Batman Returns, Iron Man 3, Carol, and Brazil have been proposed on a similar basis: they are Christmas films because they are set during Christmas, and this is, of course, the main requirement of any such label. That we all, in deepest heart, understand these films to exist in a somewhat different cultural context is, in such a contrary list, thrown aside. It is perhaps worth remembering that many genuine Christmas classics — like It’s a Wonderful Life or Meet Me in St. Louis — are not entirely, or even mostly, set during the season. There seems to be a mood that pervades these films that does not require constant snowfall, much in the way that constant snowfall does not elevate the alternative list to the standard understanding of what makes a Christmas film. But there is, between these two traditions, one curiously lodged outlier. Perhaps most outrageous of the pseudo-Christmas canon is Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley Kubrick’s last and most explicit adventure, an erotic horror (rarely sensual, often funny) and credible candidate for least appropriate film to screen at the local orphanage on Christmas Eve. But despite the complaints of the orphanage, it seems to me that Eyes Wide Shut does not, in fact, belong to the ironic Christmas Lights Make Christmas Film tradition, but is in fact — in its bones and sinews — a restatement of the most conventional Christmas theme. Which is to say, Eyes Wide Shut is, without ironic smirk, a Christmas film.

But what is the most conventional Christmas theme? A combination of the colors red and green; the presence of Marx-like redistributor; a Savior born to a Virgin in a Barn, as accompanied by Ass and Ox? None of these things. The essential theme of Christmas is in Family Reunited. Scooping at random from the broad canon, this theme is frequent: take, for instance, the aforementioned It’s a Wonderful Life and Meet Me in St. Louis, and add to that number How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Elf, and The Muppet Christmas Carol. Each of these films represents as its essential drama the conventional Christmas ideal (which is a family together, at leisure) and then the transgressive, perverse alternative (solitude, often in the context of hard work or scheming). I will justify each briefly. It’s a Wonderful Life features a family torn asunder by capitalist greed, and climaxes with George contemplating suicide at a bridge-side. He is utterly alone, and utterly divorced from that amorphous “spirit of Christmas.” But he is convinced by a guardian angel to stay his hand; the film ends in the family together again, happy despite the slings and arrows of the world. Meet Me in St. Louis is an extended goodbye to childhood, and the old world: Mr. Smith’s new job will require the family to up sticks and leave St. Louis — a family uprooted to the city is, in the scope of the film, a family disarrayed. But the ending is, again, one of restitution: they will stay after all, together in their old home. In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, we watch as an outsider plots his revenge against a consumerist hell-Christmas, only for his scheme to inadvertently bring together the squabbling townspeople of Whoville, himself now included in their number. In Elf, an attempted family reunion goes awry when Walter shows himself too serious, and too engaged in his soulless job, to see the people who depend on him. The film, again, ends in a realization that a family, together, is the most important thing. At last, the urtext, The Muppet Christmas Carol, in which the cantankerous Scrooge must learn that lonesome industry is not the key to happiness, and so he resolves himself to spend Christmas with Bob Cratchit’s family, and all but adopt Tiny Tim as his own. In all these films we encounter first the transgressive element, and then the restorative. Typically, there is some response or reaction to the perverse material condition of the world. These characters are either subject to the harshness of greed and miserliness (as is George in It’s a Wonderful Life, and the Grinch in The Grinch), or else themselves tied up in its requirements, finding themselves committed to a job or ambition prioritized above their family. We intuit, by tradition alone, that to be apart from family at Christmas implies a transgression of social norms; that it is, in the most general moral sense, perverse to, in any way, reject this standard of behavior. It is, therefore, a celebration of convention’s triumph: that no other value, no other prize, can step beyond that most basic family unit.

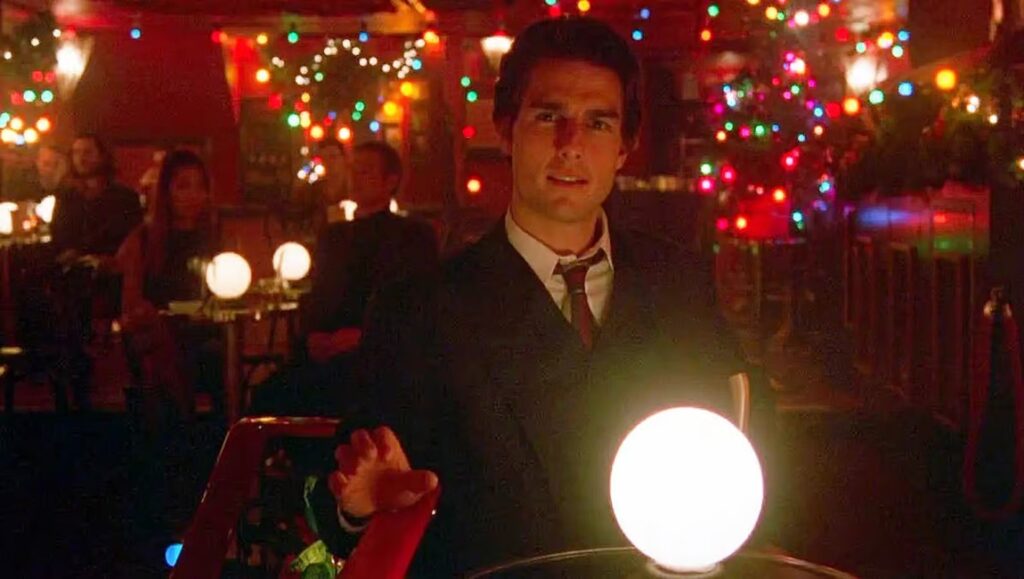

So we skate toward Eyes Wide Shut, which might, on its face, bear little in common with the previous quintet. Indeed, it might seem appropriate to identify Eyes Wide Shut as, itself, a transgressive film, which engages in the exact material that the abovementioned are specifically designed to repudiate (or at the least, ignore). It’s a landscape defined by the omnipresence of sex and death; it’s a strange, frightening dream of a man who delved too deep; it’s a psychodrama that questions the basic sexual integrity at the heart of monogamous pairing. And yet, it is moreover something else. It might be better understood as the story of an entirely conventional man, who, upon realizing his conventionality, attempts to surmount it. In so attempting, he fails disastrously. We are introduced to Dr. Bill Harford as a man at the peak of his social ladder: he’s a doctor; he’s beautiful, and he’s married to beauty; he’s invited to swanky parties, hosted by swanky people, and held in their utmost trust. Throughout the film, he will use his status as a doctor to wheedle into doors that would otherwise be locked or squeeze information out of someone otherwise unwilling. In the most conventional sense, Dr. Harford has reached the acme of his ambition: he belongs to the upper caste, and therein is secure. But it’s tough to think of another film in which Tom Cruise has seemed so short — it does not seem a coincidence. From the very onset, Kubrick whittles away at this image of proud security. First, this comes through Harford’s wife, who seems in some pattern dissatisfied with her marriage, and who will later — at comic length — describe her sex-fantasy about some passing sailor. Here, the image shatters: Bill is not the ultimate master of his destiny, but entirely in the trust of someone who is not, as he had assumed, an entirely domesticated woman. This fantasy — this dreamworld — seems in some way to speak to his own: that he has not reached the summit; that there are things that he desires that he cannot have; that there are rooms he cannot enter; that the wife, the child, the job — these are not the end. Jolted by his wife’s (ultimately meager) confession, Bill stumbles out into the world, apparently seeking some means of rebalancing his psychology: which is to say, he intends to cheat on his wife. But the film becomes a kind of comedy of manners, in which the extreme difficulty of infidelity apparently presents itself to Dr Harford. Despite his best efforts, he can never consummate this new fantasy. Instead, quite by mistake, he inveigles himself into the twilight realm: into the things that occur behind the doors through which he is not admitted; the deep end of the fantasy. Here, Bill discovers, is the dreamworld his wife had visited; here is the outcome of throwing aside all conventional security and devoting oneself utterly to the extremes of sex and death. To transgress all bounds; to forgo what is nominal and what is public. Bill finds that while he stands on the top rung of one ladder, he is below the very bottom of another: and that attempting to leap from one to the other risks a plunge into the uttermost abyss.

But the essence of Bill’s nighttime adventures — and of his wife’s parallel dreams — are in following some inner ambition, and responding to the texture of the world. If we understand 2001 as Kubrick’s natural selection film, perhaps we should understand Eyes Wide Shut as his sexual selection film, in which sex becomes an ultimate objective, both in opposition to and in twirl with death. Each exist at the extreme of human experience, the one creative and the other destructive. It would appear, in this expression of reality, that the accumulation of capital and title are, ultimately, the fiat exchanged for ever-more-gratuitous sexual access (and Bill experiences the total gamut: beginning with his wife, then floozies at the party, then a bereaved woman who thinks she loves her doctor, then a street prostitute, then a more invidious kind of prostitution, then the ultimate exchange, in which high status allots one entry into a new kind of ritual). But Bill must, at the last, curtail his ambition. Indeed, it appears that an exposure to this wider world has recontextualized his understanding of reality. He is not at the peak of the social pyramid; nor does he want to be. He is not the utmost in his world; nor is he made to be. The transgressive world appears to him a horror — as though the simple attempt at infidelity revealed to him a world in which all social norms slowly peel off, and he is at the mercy of things he cannot begin to understand. This, as becomes the essentially conservative notion in Kubrick’s film, is the risk of transgression. To throw away the Known and find oneself in the realm of the Unknown, long since inhabited by another kind of man. If dreamt or experienced (and the film blends these modes), the response is the same: the conventional man must realize that he is conventional, and therefore return whence he came. And here, amid the Christmas lights and the fir trees, is where Eyes Wide Shut snakes its way into the most traditional canon of all. Because Bill has, in essence, become like the many flawed protagonists or antagonists of the Christmas cinema: he has transgressed his familial role, in search of a greater ambition, himself as an individual triumphing over whatever group responsibilities he might possess. Typically, this transgression is represented by an overabundance of work: but work is simply a representation of gain, of perverse effort put toward an exterior fantasy, or ambition. But in this case and the others, there is a peace and a serenity in returning (even with tail between legs) to the dimensions of the monogamous, nuclear family. To have strayed, briefly, into another — a colder — world; to have lost sight of those essential, comfortable, conventional pleasures that exist within the department store, in the Christmas season, with wife and with child. Kubrick’s advice to Bill Harford is to remain exactly where he is: to weather the storms; to keep holidays; to heed the word of his hauntings. Like Scrooge, he is not destroyed by these foul sights and visions, but renewed. Christmas Morning at the Harford’s will be like any other year. And after the publication of this piece, perhaps the Christmas Mornings of many a family will be augmented by reflections on the previous evening’s screening of Eyes Wide Shut, attended by young and old, amid the tinsel, the tree, and the snow-clad lintels. Therein, the true moral of the Christmas film: Family Reunited.

Comments are closed.