It’s girthy, oversized, gold-encrusted, evocative of pain more than pleasure. No, I’m not talking about the massive enameled penis that makes a couple appearances throughout Caligula: The Ultimate Cut; I’m referring to The Ultimate Cut itself. This newer version of the maligned 1980 film has been reconstructed entirely out of previously unseen footage, rendering it a wholly different artifact. Whereas the original was hijacked by the pornographic tendencies of Penthouse founder Bob Guccione, resulting in a turbulent post-production that slighted many parties in its wake, this “remix” attempts to reclaim Tinto Brass and Gore Vidal’s original vision. Maybe it accomplishes that, but there’s no crystalline way to determine so. What can be observed, however, is that The Ultimate Cut doesn’t so much elevate the material as it does laterally reconfigure its purpose.

Nobody wants a history lesson, especially not from me. It would be a bland, uninformed retread that reads more like a textbook blurb than an enlightening piece of criticism; and besides, Caligula as an intellectual property in any of its versions resists historicization. All one needs to know about its narrative is that Tiberius passes away (synonymous with murder in the context of the Roman Empire) and Caligula is crowned the new emperor, thereby descending further into excess and unregulated power, which quickly devolves into paranoia, mania, and wanton violence. Beyond this basic foothold, Caligula 2.0 is really all about the aesthetics; it’s still in poor taste like its predecessor, still gratuitous and sleazy and uncomfortable and often downright absurd, but the way it’s been re-edited situates the film’s stylistic overreach as far more political than titillating.

There’s nothing uniquely filmic about Caligula, aside from a handful of crash zooms and other wispy camera movements characteristic of the decade in which it was produced. It’s more in-line compositionally with earlier historical epics like Ben-Hur or Cleopatra, with theatrical sets, proscenium framing, and overstated acting. This one has a subversive streak, though, in its ability to overwhelm with cruelty through extensive lingering, lurking, leering, accumulating, like a Frankenstein’s monster of cinema and theatre’s nastiest abilities. Within any given set piece, Brass makes sure to focus in on certain elements, just long enough to brand our memories with confusion and disturbance, like Tiberius’s sex dungeon for example: extras can be seen choking on fluids, penetrated by stakes, swinging on malicious-looking trapeze devices, sitting on each other’s faces in aggressive, unsexy ways — like they’re intending to suffocate, or defecate on, their accomplice — and sometimes there are just piles of human bodies writhing grotesquely, often with a disembodied penis sticking out from some hole or another.

While this is all framed mostly in a theatrical, big stage piece kind of way, we do get closer glimpses (maybe thanks to the re-edit?) of the bizarre, orgiastic happenings in the background. Without the more stylistic compositions briefly intercut throughout, all of this would mostly just look like distant, silhouetted tapestries of bodies implying that sex is occurring. And that’s exactly where The Ultimate Cut radically diverges from the original — it transforms the mood of Caligula’s cloistered chamber drama from one of mostly sex (unsimulated and penetrative) with some violence sprinkled in, to a film that is instead all about sexual violence. Visceral all the same, but less pornographic and more just… graphic. The wedding scene cements this, more than one could ever stomach.

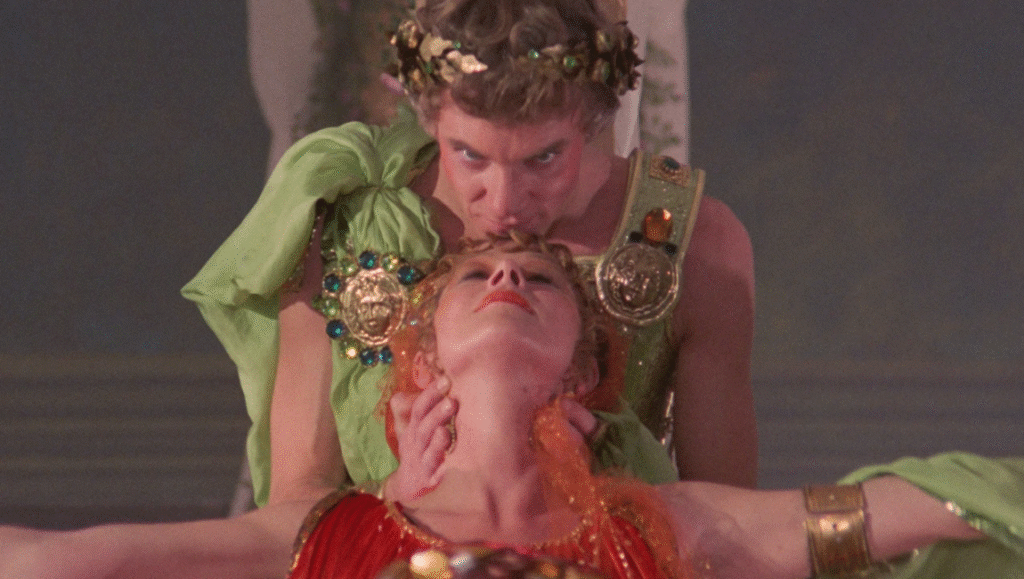

At the midway point of The Ultimate Cut’s three-hour runtime, the emperor arrives at the wedding of a young couple. The groom was a soldier whom Caligula previously tried to have executed for a crowd’s entertainment, simply because he could. As revenge for the soldier evading death, our noble protagonist decides to bless the newlyweds by raping both of them. The bride is first; he spreads her legs painfully wide and inspects her, determining she’s a virgin. He leaves her shaking and in tears, covered in blood from her vagina. Next up is the groom; Caligula man-handles him with lube from what looks like a comically large jar of lard. He bends the man over, the wife in fetal position right beneath them, and violates him just as aggressively. This scene goes on for what feels like 20 minutes, is incredibly difficult to endure, and serves as the turning point between Caligula’s previous clownishness and youthful anarchy in the first half, and the relentless scourge of the second half.

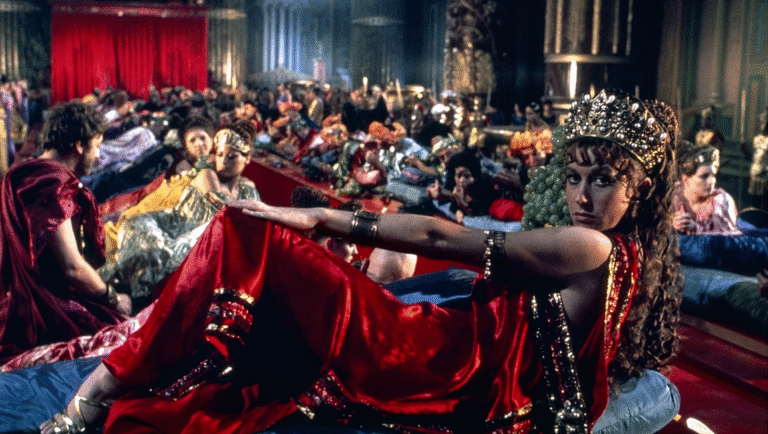

If all these details didn’t cause you to rethink your admiration for sanitized Roman pop culture like Gladiator II or the social media trend of boyfriends being obsessed with the Roman Empire, the latter act of this cut very well might. It’s filled with even grimier, more mean-spirited power trips. There’s a sex party populated mostly by the wives of Caligula’s senators, done purposely as a flex (did I mention that this sex party takes place on a giant replica ship with oars and that the revelers are forced to row and simulate a deep sea voyage?). There’s Caligula’s “invasion” of Britain, where he sends a bunch of naked foot soldiers and centurions to attack a papyrus tree. Just for fun. Caligula also has a threesome with his biological sister and Helen Mirren. Then we have a twisted game of Simon Says that ends with most of the participants being arrested, regardless of their success or defeat in the game. The emperor’s horse Incitatus is designated as consul in front of everyone who presumably was an actual candidate for the position, and Incitatus closes this segment with a Looney Toons-esque shart. Elsewhere, there’s a full-frontal of Malcom McDowell pissing on a pillar; Helen Mirren chained to poles in front of an audience, King Kong-style, while she gives birth to Caligula’s heir; a large car-wash-like mobile wall of feathery tentacles grazing over people’s heads while they dine on intestines and other unidentifiable organs. And finally, we arrive at assassination by Senate as Caligula is butchered en masse, like Hitler in Inglourious Basterds. As a little bonus, we get a glimpse of his innocent toddler daughter flung like a ragdoll face-first into marble steps, a spatter of blood staining its surface, indicating that Caligula’s line of power is officially severed.

Was that an exhausting list to read through? Well, congrats; you’re now conditioned to sit through Caligula: The Ultimate Cut. If there’s any major accomplishment or “elevation” in material to be found with this new version, it’s that it situates itself somewhere in between the aesthetics of the Theatre of Cruelty and the Cinema of Cruelty. The founding artist-theorist of this school of thought was Antonin Artaud, who outlined in his dense collection of manifestos, The Theatre and its Double, a kind of theatrical vision that would eschew “the idolatry of masterpieces” and offer not an intellectual experience but one that would “shake the organism to its foundations and leave an ineffaceable scar.” Artaud’s theater aims at disturbing the senses, pushing the audience’s experience to new extremes, revealing our cultural hypocrisies, and releasing subconscious, as well as anarchic, impulses. In these respects, he says, it resembles the plague, which is likewise “a delirium and is communicative.”

Watching The Ultimate Cut is less like watching a classic costume drama or a historical epic, and more akin to the feverish, overwhelming expressionism of something like Artaud’s own play, The Spurt of Blood, which has scarcely been staged due to its unkempt script language that involves everything from a giant nun menstruating scorpions from her vagina to a full-blown hurricane overtaking the action onstage. Reminiscent of Caligula’s carnivalesque brutality, no? The giant golden dildo; the statue in a palatial pool that has a gaping, fluorescent-red vagina etched into it; anatomically accurate wedding cakes; idiosyncratic devices (like Tiberius’s elevator that is being operated by nothing in particular) used for ambiguous acts left for us to decide whether they’re violent, fetishistic, or both; that unfathomably large baby head protruding from Helen Mirren’s prosthetic vagina while she’s on display. It’s all delirious, demented, and yet always linked with a critique of imperial power — asurface-level, hammer-to-the-face sort of critique, which Artaud considered a productive route to something deeper.

This remix of Caligula goes further than (or maybe just transmits) Artaud’s stage language, in that it exists in the cinematic medium. Artaud himself also wrote on the nature of film despite being mainly a dramatist; like the stage, he emphasized a film aesthetic that could “de-psychologize” our reliance on narrative, dialogue, and characterization, having particularly associated cinema’s revolutionary potential with early cinema’s presentational or exhibitionist visual tropes and with practitioners such as Charlie Chaplin, who built on this representational logic. Primitive cinema’s presentational mode of representation affected all aspects of the narrative, and this privileging of showing images, gestures, and actualities did not subordinate all the visuals to a central idea/conflict around which the narrative revolved. At times, the captured images played a disruptive role and did not promote narrative continuity and harmony.

Caligula’s very origin is a disrupted one, having been dissected, its organs rearranged into something primarily geared toward pleasure. The original version is intercut with countless images of unsimulated sex by pornographic actors, leaving what was left of the dramatic footage disparate, disjointed, lacking any sort of message beyond just being a “period piece” with a lot of fucking. The Ultimate Cut is still very much a patchwork, imperfect, with vast holes in its narrative, but it’s new construction now registers as a calculated aesthetic choice to this writer, one which lends the film a vicious pulpit. Untethered from the noxious history of its original cut, this re-edit is capable of achieving what Artaud had pondered: a visceral, physical, purely carnal tableau of cruelty that is not reined in by ulterior motives or convoluted plotting. It’s not trying to be a masterclass in storytelling or drama, nor is it aspiring to white-knuckle entertainment value. Its shape is that of multiple spurts of blood, of all shades of red.

In this way, The Ultimate Cut can feel simultaneously like watching a New French Extremity film and a Buster Keaton gag, or like witnessing Vanya from Anora if he were a raging sadist instead of just stupid. Or maybe it’s better to put it this way: instead of spending two hours in an orgy (Caligula 1.0), we can now spend three hours in an orgy that seems inescapable and increasingly non-consensual (Caligula 2.0). An orgy turned frightening, hopeless, perpetual until everyone’s in the grave and Malcom McDowell is defecating on our headstones with a devilish smile.

1 Cardullo, Bert, and Robert Knopf, editors. Theater of the Avant-Garde: 1890 – 1950. Yale UP, 2001, 375.

2 Koutsourakis, Angelos. “The Dialectics of Cruelty: Rethinking Artaudian Cinema.” Cinema Journal, vol. 55, no. 3, 2016, p. 72, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/619510. Accessed 21 June 2025.

Comments are closed.