A Streetcar Named Desire is so iconic within cinema history that the film itself can easily be taken for granted. One could boil down its legacy, all too simply, to its ushering of Marlon Brando into movie stardom — bringing with him Method Acting and new models of masculinity to Hollywood — and the actor’s much-referenced keening for “Stella!” in the film’s most famous scene. The complexities and innovations of A Streetcar Named Desire, though, still resonate beyond its lofty, yet narrow, reputation. Elia Kazan’s 1951 film version of Tennessee Williams’ era-defining play still functions as a compelling, slippery moral drama, occurring within an aesthetic space that provocatively slips between the expressionistic and the naturalistic. Truth and illusion, or “realism” and “magic” as delineated by doomed protagonist Blanche DuBois, are a constant ground for debate between the film’s sparring characters. Streetcar itself remains striking for how it navigates between these two poles, and blurs the lines between them, in both form and in content.

Kazan’s film begins at a train station, with Blanche (Vivien Leigh) emerging, delicate and weary, out of a puff of steam. Leigh’s fragile appearance echoes how Williams describes Blanche’s first entrance in the text of the play the film is based on: “Her delicate beauty must avoid a strong light. There is something about her uncertain manner, as well as her white clothes, that suggests a moth.” Blanche has arrived in New Orleans from Auriol, Mississippi, to visit her younger sister, Stella (Kim Hunter). Stella shares a shabby apartment in the French Quarter with her husband, Stanley Kowalski (Brando), and the genteel Blanche is shocked by how her sister lives. Yet Blanche has lost her family’s estate, Belle Reve, after generations of financial mismanagement and the deaths of all of her and Stella’s remaining family, and she has no choice but to stay with Stella and Stanley indefinitely.

Blanche and Stanley, instantaneously, are mutually wary. Blanche sees the working-class, masculine Stanley as rough-hewn and animalistic, while Stanley resists what he sees as Blanche’s put-on patrician airs, and he is particularly skeptical of her coquettish flirtations. Stella, caught in the middle as their mutual animosity increases in intensity, wavers between her loyalty toward her beleaguered sister and her all-consuming desire for her husband — yet it becomes increasingly clear that the scales are tipped toward Stanley, particularly considering that Stella is pregnant, and regardless of Stanley’s frequent physical violence. Blanche, as her status in the Kowalski household grows increasingly precarious, pins her hopes on Harold “Mitch” Mitchell (Karl Malden), a fellow factory worker and Army buddy of Stanley’s. Mitch is attracted to Blanche and charmed by the very mannerisms that repel Stanley, and Blanche carefully guides their budding romance in the hopes that he will propose marriage. Stanley, though, cannot abide a close friend being taken in by a woman he sees as a manipulative interloper, and he weaponizes incriminating information about Blanche to destroy their relationship and expel her from the apartment. Blanche, whose mental state was tenuous when she arrived in New Orleans, deteriorates even further as a result of Stanley’s outright hostility, and their power struggle culminates in a devastating encounter that leaves her very sanity on the line.

The film version of A Streetcar Named Desire began to take shape not long after its massively successful 1947 Broadway production. Independent producer Charles Feldman bought the rights, secured production and distribution with Warner Bros. Studios, and reassembled nearly the entire Broadway cast and crew, most notably director Kazan; playwright Williams (who co-wrote the screenplay with Oscar Saul); and actors Brando, Hunter, and Malden. Vivien Leigh was the only major new addition. Jessica Tandy had originated the role on Broadway, but the studio sought a higher-profile actress for the film, and Leigh, long cemented in the public’s imagination as the quintessential Southern Belle in Gone with the Wind, had recently played Blanche in London under the direction of her husband, Laurence Olivier.

Censorship greatly affected how the film would eventually be presented. Williams’ play directly addressed many topics verboten for Hollywood cinema in 1951, when the censorious Production Code enforced by the studio system was beginning to waver, but was still potent. Stanley’s machinations lead to an incremental series of reveals that Blanche was fired from her job as a high school English teacher for having sex with a 17-year-old student, and that she had stayed in a seedy hotel, taking in a long series of anonymous lovers, both of which led to her becoming a social pariah. She also reveals to Mitch, in a vulnerable moment, that her late husband, Allan Grey, had died by suicide after Blanche had walked in on him having sex with another man and publicly shamed him for this act. Just as Blanche’s character is largely defined by sexual experiences that could not be depicted, let alone described, in studio-era Hollywood films, Stanley and Stella’s relationship is defined by a heavy, irrepressible sexual desire, and the climactic scene — resulting in the final destruction of Blanche’s psyche — is Stanley’s rape of Blanche.

After a protracted back-and-forth with the Production Code office, any reference to homosexuality was scrubbed, the rape was maintained but made more subtle and implicit, and the final scene was altered: rather than letting herself be consoled by Stanley as a psychiatric doctor ships Blanche off to a hospital, Stella resolves to leave him. A potential condemnation from the Catholic Legion of Decency also compelled Kazan to make cuts to ensure the film’s distribution, mostly relating to Blanche’s sexual history and the sexual desire between Stella and Stanley. These five minutes of excised footage were restored in 1993, and the fully intact version is now the most widely accessible version of the film.

Despite the sanding-down of its more provocative edges, Kazan managed to maintain the core thematic elements of Streetcar: within a stifling domestic frame, the film encompasses the power struggle between an emissary from a dying breed of American life and a representative of post-war progress and social change; the extreme extents to which desire can dictate someone’s actions despite their better judgment; and the cascading effects of one set of personal myths and narratives conflicting with another’s. Kazan maintained a theatrical style, focusing on long, dialogue-heavy scenes with limited camera movement and deep attention to the actors’ performances.

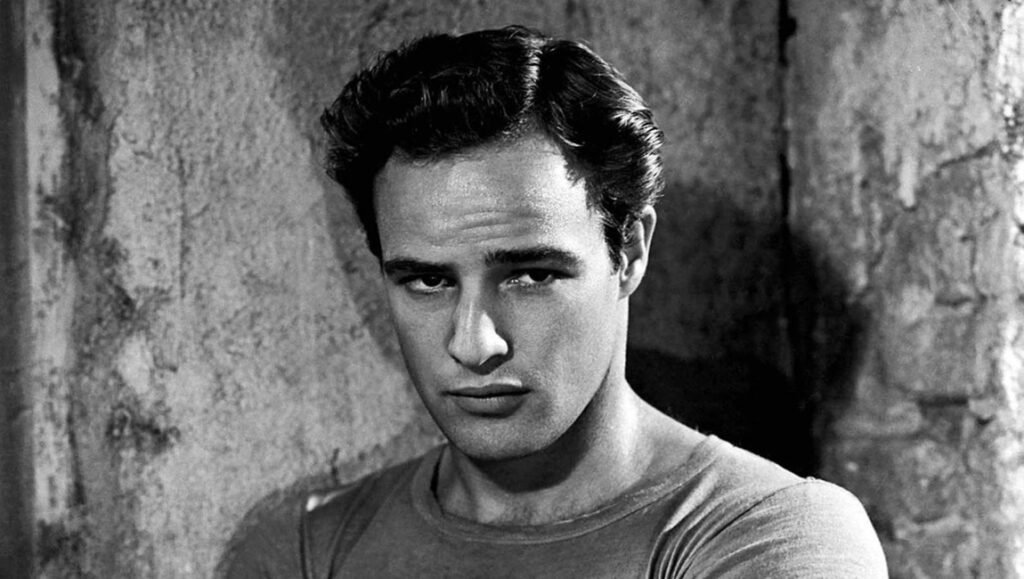

The focus on performance was a logical one, befitting the robust characterizations of the screenplay, yet it also provided an opportunity to showcase four seismic performances. The styles and backgrounds of Leigh and Brando lend a meta-cinematic component to the film. Brando, along with Hunter and Malden, had trained in Method acting, a catch-all term for a set of psychological, internal-focused approaches to acting derived from Konstantin Stanislavsky that were popularized in the United States by teachers including Stella Adler and Kazan himself, both of whom Brando studied with. Leigh, for her part, was a classically trained actress of the British stage who also excelled in Hollywood. It was a dynamic that was reminiscent of Brando’s tense relationship with the stalwart professional Tandy in the Broadway production of Streetcar; time-honored, externally-focused acting styles collided with the interior, unpredictable, and often thrilling new Method — paralleling how, in Streetcar, the faded Southern aristocracy clashes with a new working-class masculinity.

Leigh portrays Blanche with a reflexive pomposity and effortful girlishness, the core of who she is emerging only in vulnerable moments — in these moments, Leigh lowers her voice to a deep contralto to contrast with her typical false, fluttery tone, a compelling and unsettling choice that also speaks to the rigorous vocal training of English actors at the time. Brando, in a livewire performance, mutters and yells, struts and sulks, talks while chewing and bursts into verbal and physical violence with the slightest impetus. It is a magnetic performance defined by Brando’s spontaneity and an unstoppable force of personality emanating from within. Hunter and Malden are comparatively more restrained, but their down-to-earth, naturalistic performances align them closer with Brando’s style than Leigh’s, further emphasizing Blanche as out of place. Impressive on their own merits, the performances of Leigh, Brando, Hunter, and Malden provide an implicit commentary on changing mores within acting and reflect the conflicts within Streetcar, generating depth and complexity and cementing the film as a turning point for screen acting.

Elements of craft inflect the film with a hazy, seductive quality, enveloping the intensely psychological performances within a dreamlike space. The cinematography, by legendary director of photography Harry Stradling, is dappled with shadows; waves of darkness wash over faces and flashes of illumination glint from shaded bulbs and the lights of the street. The noir-adjacent visual strategy follows Blanche’s own relationship with light: self-conscious of her age, she avoids direct, bright light as a matter of course. Alex North’s score, the first notable jazz score in a major Hollywood film, is seductive and seedy, expressing both the gritty urban environment and the character’s roiling desires. The costume design by Lucinda Ballard, who designed the Broadway production, emphasizes Blanche’s fading beauty and anachronistic self-presentation and Stanley’s raw sexuality: frilly, fading dresses for Blanche, tight and seemingly constantly ripped white T-shirts for Stanley. Oscar-winning art director Richard Day and set decorator George James Hopkins crafted a seamy and haunted-looking apartment complex where nearly all of the film is set; far from a naturalistic depiction of the French Quarter, it is a physical expression of the psychological turmoil and physical constriction experienced by the central trio of characters.

Stanley’s predation and Blanche’s slow slide into delusion become progressively more harrowing to watch, and the film’s aesthetic discord between the gritty reality embodied by Stanley and the gossamer fantasy of Blanche’s mindset becomes accordingly more intense at both poles. On its surface, Blanche’s final descent into insanity reveals the untenability of her choice to blend fantasy and truth, and the victory of Stanley in imposing his style of brutal reality on every corner of his life. Yet complications endure: Blanche, in unguarded moments, is direct and unsentimental about the choices she has made in her life and the struggles she’s experienced, and her choice to embody a fantasy to avoid the harshness of reality begins to seem like a rational way for Blanche to persevere despite her life’s many devastations. Stanley, on the other hand, is so impetuous and uncomprehending of Blanche’s mindset that it becomes clear that his perspective is that no way of moving through the world other than his own should be accepted. That his relationship with Blanche culminates with a rape that he then lies to Stella about — and just after she has given birth — suggests that he is just as comfortable manufacturing a fantasy, and compelling others to accept it, as Blanche.

The brilliance of Williams’ work, and of its cinematic interpretation shepherded by Kazan, is that by Streetcar’s conclusion, Blanche’s apparent weakness seems more like an inveterate strength that has been pushed to its limits, and Stanley’s apparent strength is in fact an all-encompassing moral weakness. The legacy of A Streetcar Named Desire rightfully reflects the outsized impact of Brando’s performance, but the intricacies of the craft and storytelling stand on their own apart from this legacy, as complex and enthralling as they were over 70 years ago.

Comments are closed.